New Paper: Social burden and bald eagle recovery

The osprey man of Tilghman

July 7, 2022

Quarry Birds

July 11, 2022By: Bryan Watts

7/10/22

Survival of the majority of the endangered species in the United States will ultimately depend on our ability to manage habitats on private lands. For many species, recovery is simply not possible without the active participation of private landowners. One of the challenges of applying endangered species policy on private property is striking an equitable balance between species protection and civil liberties. The heart of the challenge centers around the term “taking” under the opposing mandates defined within the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Under ESA it is unlawful for a private citizen to “take” any species classified as federally Threatened or Endangered. Among other actions, the term “take” refers to disturbance or significant habitat modification. Restrictions on the free use of private land that arise from the prohibition on take under ESA are often viewed to represent a “taking” of private land by the public as prohibited under the Fifth Amendment which states “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

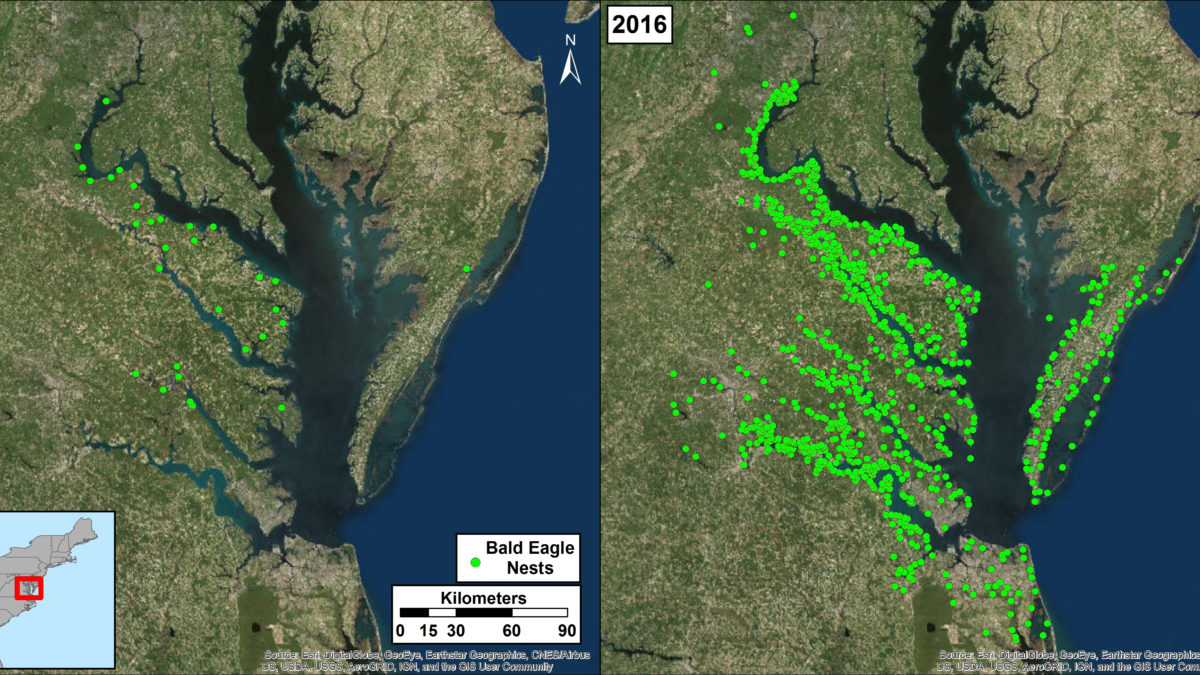

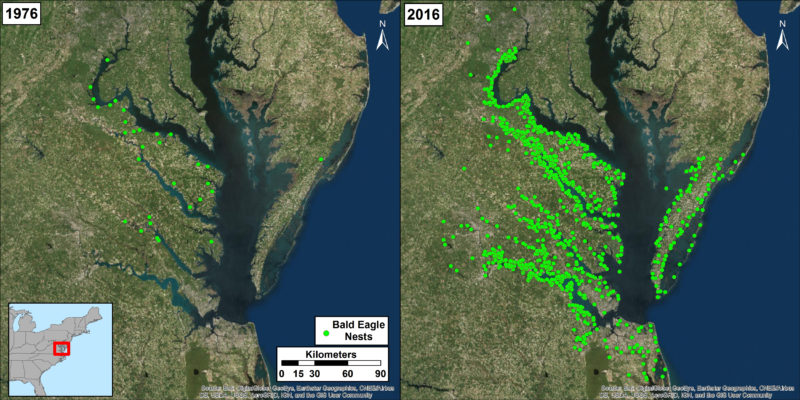

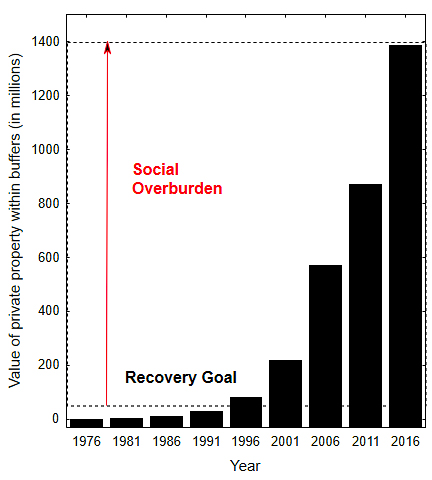

Bryan Watts and Mitchell Byrd recently published an article in the journal Conservation Science and Practice entitled, “Policy and the social burden of bald eagle recovery.” The paper examines bald eagle recovery in the lower Chesapeake Bay over a 40-year period and quantifies the burden of applying ongoing management guidelines on private landowners in light of recovery. They quantified two metrics of social burden including 1) the area of private land within federal management buffers and 2) the market value of private land within management buffers.

Between 1976 and 2016, the number of bald eagle pairs within the lower Chesapeake Bay increased exponentially. The breeding population exceeded the numerical recovery goal as established by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service recovery plan in 1994. In lockstep with the eagle population, the total amount of land falling within critical habitat buffers increased from 384 to 10,670 ha. In 2016, the percentage of land within restrictive buffers accounted for by privately held lands was 80.7 (8,607 ha). The estimated value of private property within regulatory buffers increased more than 900 fold (1.53 million to 1.39 billion) during those 40 years. This dramatic increase in the value of private property “under regulation” is due to 1) growth in the eagle population, 2) the increase in overall property valuations and most significantly and 3) the increased colonization of urbanized jurisdictions with markedly higher property values. The estimated value of properties in 1996, two years after numerical population goals were met, was 79.5 million such that 94% (1.31 of the 1.39 billion) of the estimated burden in 2016 had been imposed since the population was deemed to be recovered. The continued application of crisis-era restrictions after the crisis has passed risks overburdening private landowners and undermining public confidence in regulatory policy. The bald eagle is a highly visible case study in regulatory overreach that resulted in the overburdening of private landowners. Restrictions on activities within private lands to achieve vanishingly small conservation benefits threaten to undermine support for conservation that depends on landowner participation. Policy makers and regulators have the responsibility to insure that the level of burden borne by landowners is justified in terms of realized benefits to imperiled species. This responsibility includes the reduction in landowner burdens as species recover and associated risks of extinction decline. The long-term effectiveness of endangered species law depends on our ability to maintain public support.