The value of old field notes

CCB Launches Shorebird Roost Registry

September 3, 2020

CCB makes technical reports more accessible

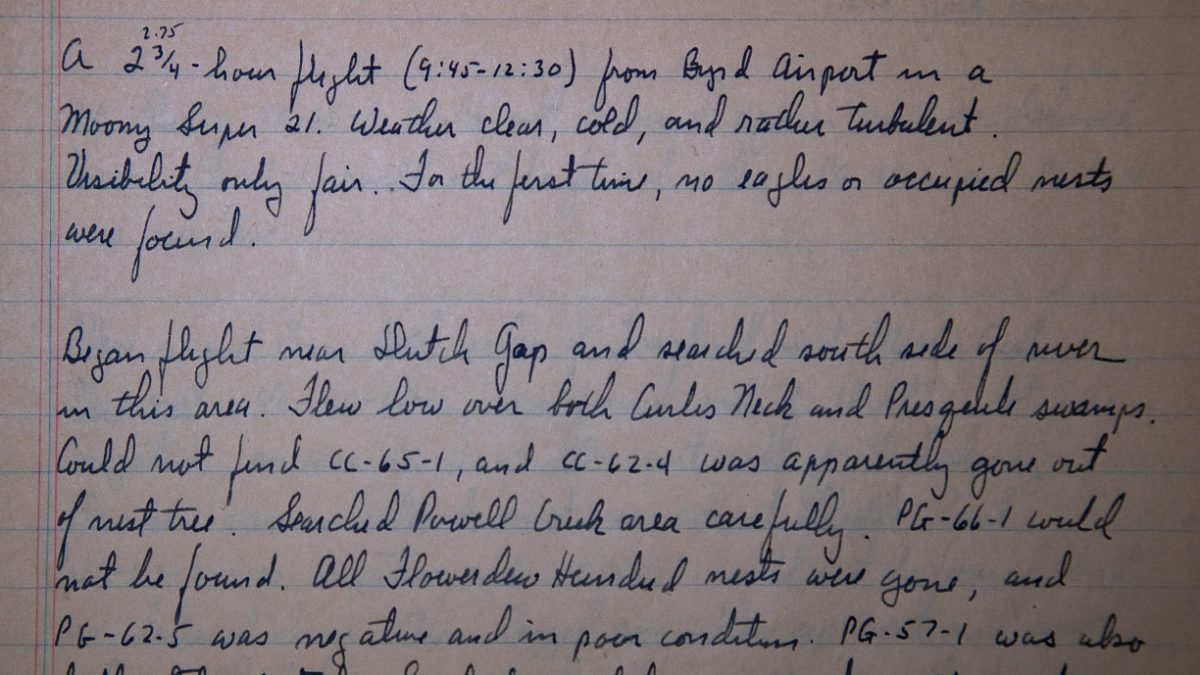

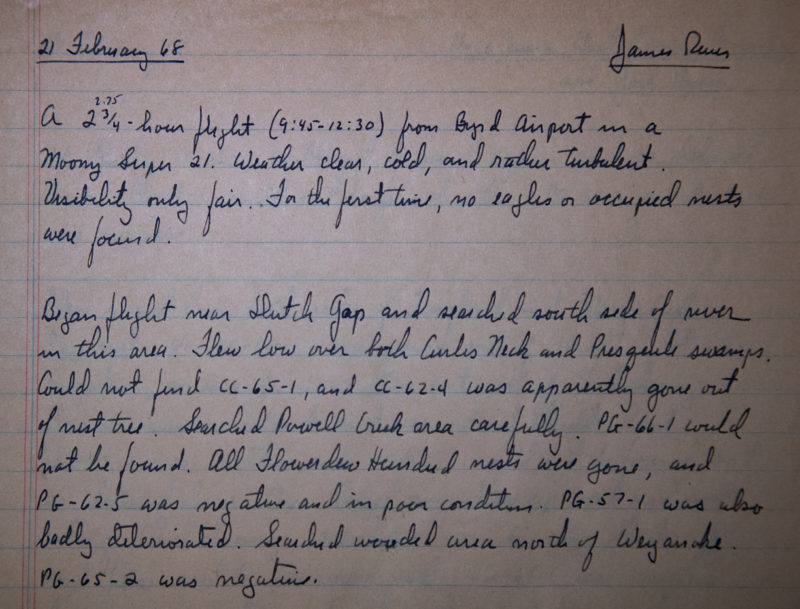

September 30, 2020Beginning of field notes made by Fred Scott on 21 February 1968 describing a bald eagle nest survey flight of the James River. The flight was made during the height of the DDT era and gives a long list of nests on the James and York rivers that were missing or empty. The Center has original notes from Fred that cover flights made between 1963 and 1979.

By: Bryan Watts

9/14/2020

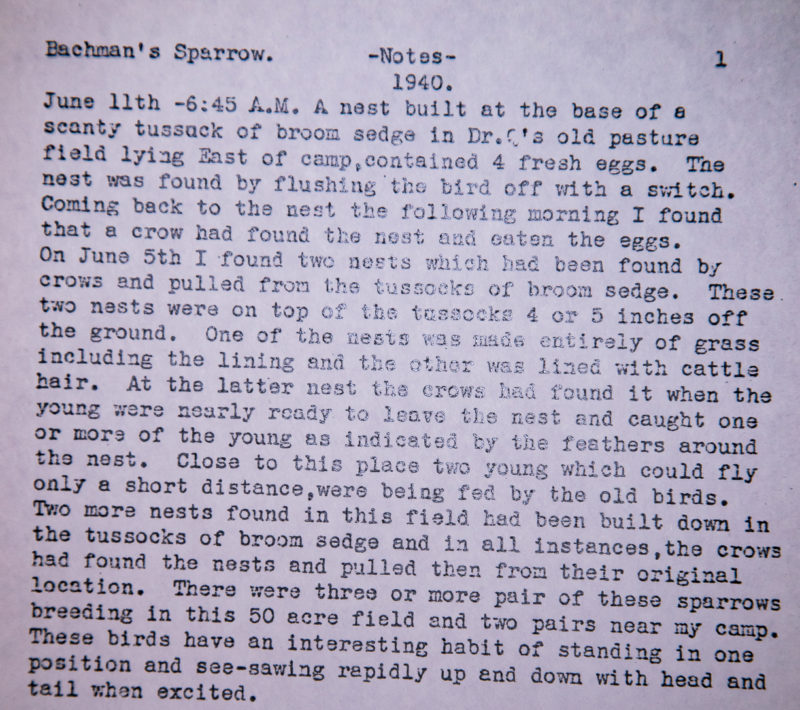

Field notes are like an artist study. Although they may lead to a published manuscript or report, they provide a more complete view of the subject than is possible within the report itself. Field notes provide a reference point in time with details that the observer has yet to digest and understand. Much later, while looking back over the notes, it is these details that stand out and contribute to deeper understanding. Rather than the summary, the seemingly insignificant details often provide the signposts that lead to discoveries.

When I was a young researcher, I thought that the natural history of a species was a dominant factor driving a breeding, winter or migration season such that the seasons were replicates moving through time. Now, many years later I know that the natural history that we observe is constantly adjusting to an ever shifting context. Individual seasons are one-offs that reflect what is happening in that year. It is the collection of observations of how species respond to year-to-year variation that provides a much richer and more complete understanding of natural history.

Field notes are unique to their time and cannot be replaced. The ecology documented in that place and time is a refection of the obstacles that the birds were confronting in that moment. Often times in order to unravel the underlying causes of population change we need to understand how birds responded to those conditions. The population may or may not confront those conditions again. Field notes offer observations of a specific time and place and clues to how species respond.

The Center for Conservation Biology has a growing collection of historic field notes that offer a view into the past during consequential periods. Some of these notes contain observations on single species that span decades. Some represent individual surveys of specific populations. All of these have value in piecing together the rich tapestry that has brought species to this place and time.

The Center’s objectives with the collection are to learn more about species of conservation concern and to make the information accessible to other researchers and to the public for use in their own work. We continue to build a digital archive of field notes that may be searchable and accessed online.

The Center continues to accept sets of field notes. If you have field notes from an ancestor or from yourself and you would like to see those notes contribute to our broader understanding of bird populations, please contact us: info@ccbbirds.org, 757-221-1645

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts