Cutting eagle trees as social experiment continues

KE on James River in Surry County Mar 20

March 22, 2014Camellia at Bennetts Creek – Suffolk Mar 23 2014

March 23, 2014

When bald eagles were removed from the federal list of threatened and endangered species in June of 2007, the action was both a conservation milestone and the beginning of a social experiment.

Recovery of the bald eagle population is arguably the greatest conservation success story in our nation’s history and a testament to wildlife law. However, pulling the population out from under the big stick of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for the first time in nearly 40 years comes with an uncertain amount of risk. Within the Chesapeake Bay, 75% of all bald eagle pairs nest on private lands suggesting that the future of the population resides with the public. How private landowners would respond to the removal of ESA protections in the post-delisting era has been an open question of interest to the conservation community.

Typical bald eagle nest tree within the lower Chesapeake Bay. This nest tree near Colonial Beach Virginia was cut down during a logging operation in the years after this photo was taken. Photo by Bryan Watts.

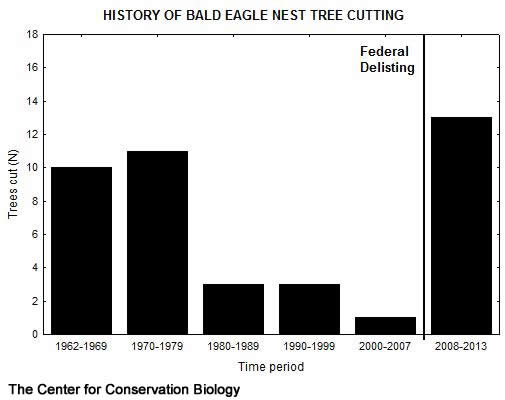

Information compiled from the annual bald eagle survey is beginning to give a hint as to how the experiment is playing out. The Center for Conservation Biology has been monitoring eagles and their nests within the Chesapeake Bay for decades. One of several objectives for this ongoing program is to observe how eagle pairs fare on private lands. Since removal of eagles from ESA protection, we have observed a clear uptick in nest trees cut (13 trees since 2007) during logging operations.

Aerial photo taken after a logging operation along the Rappahannock River cut an eagle nest tree. This forest block supported a bald eagle nest for ten years prior to the harvest. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Loss of nest trees to logging is not new to the Chesapeake Bay population. Following his historic survey of bald eagles within the Chesapeake Bay, Bryant Tyrell reported in 1936 to Richard Pough of the National Audubon Society that lumbermen were cutting several nest trees per year. He reported that “their attitude was one of absolute disregard for the eagles”. In general, the lumbermen were not selectively targeting nest trees, but they were cutting entire forest blocks that contained them. This practice continued and was well documented by the annual eagle survey during the 1960s and 1970s. By the 1980s, news of the eagle’s plight and penalties under federal law were more widely known, and the number of trees lost to logging declined substantially.

Graph of documented nest trees harvested (1962-2013) in the lower Chesapeake Bay. It should be noted that the number of nest trees in the population increased substantially over the 50-year period. Data from CCB.

Cutting of bald eagle nest trees continues to be a violation of federal law. Although the species no longer enjoys ESA protection, both bald and golden eagles are unique in the United States in having their own federal law (the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1941, commonly referred to as the Eagle Act). Delisting eagles in 2007 effectively initiated a change in the lead legislation used to prosecute eagle violations from ESA to the Eagle Act. There has been very little change in the recommended federal management guidelines pertaining to bald eagles (http://www.fws.gov/northeast/ecologicalservices/eagle.html).

The recent increase in cutting of nest trees may reflect a broader public misconception that nests are no longer protected following their delisting. We, the conservation community, need to be more effective in communicating landowner responsibilities under federal law.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

March 21, 2014

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts