Reproductive effort of red-cockaded woodpeckers at Piney Grove a result of age before beauty

Mercury levels in Chesapeake Bay bald eagles

July 12, 2010Studying eagles along the lower Susquehanna (Conowingo)

July 14, 2010

Written by Michael Wilson

July 13, 2010

Ten-day old red-cockaded woodpecker nestlings receive their color bands so the Center for Conservation Biology may track their survivorship and activities during subsequent monitoring efforts. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The population of red-cockaded woodpeckers (RCW) at The Nature Conservancy’s Piney Grove Preserve in Virginia represents the northernmost residency of the species in the United States. Over 100 years ago, the range of the red-cockaded woodpecker used to extend further north through coastal Maryland and into New Jersey. Drastic losses of old-growth pine habitat throughout the 20th century reduced woodpecker populations to 1 % throughout their former range in the United States and when the dust settled the change had redefined Virginia as the new northern boundary. However, by the year 2000, only 3 of the original 23 breeding groups detected in Virginia in 1977 were still remaining. These 3 remaining groups were located within an old-growth loblolly pine forest subsequently purchased by The Nature Conservancy as a red-cockaded woodpeckers preserve. The Piney Grove Preserve birds are now the last line of defense in preventing the range from being redefined again as one state further south. The Piney Grove population is also recognized as an essential support population for the Mid-Atlantic Recovery Unit which includes Southeast Virginia and Coastal North Carolina. Piney Grove and the remaining region Unit must reach a population of 70 potential breeding groups before red-cockaded woodpecker can be legally removed from the Federal Endangered Species list.

Figure 1. Persistence of annual fledgling cohorts into the year 2010 for red-cockaded woodpeckers at TNC’s Piney Grove Preserve. Graph by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Over the past 10 years we have been able to witness the population of red-cockaded woodpeckers at Piney Grove become healthier with an increase from 3 to 8 potential breeding groups and a doubling in the number of birds from 21 to 42 individuals. This outcome was only made possible with significant management of the habitat (such as timber removal and prescribed burning), cavity competitors, and the woodpeckers themselves.

Population monitoring is an essential component for managing the Piney Grove population with success. The woodpeckers at Piney Grove are monitored year-round between seasonal surveys that acquire head counts and the survivorship patterns of individual birds and more intensified breeding monitoring used to determine the reproductive output of the population. All RCWs at Piney Grove are banded with a unique combination of color bands and USGS serial band so we may identify the presence or absence of each individual in the population through time. We are also able track each birds location, breeding status, and helper status. Having these data is important for determining the value of management actions such as the assessment of translocating 25 birds from donor populations in North Carolina and South Carolina to Piney Grove since 2002.

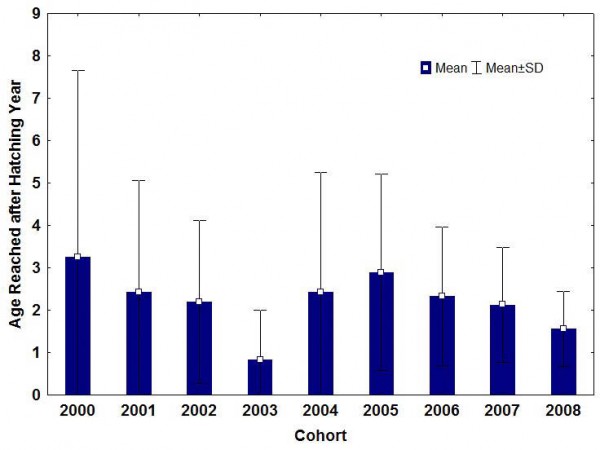

Figure 2. Average survivorship of red-cockaded woodpeckers for annual cohorts of fledglings produced at TNC’s Piney Grove Preserve. 2009 and 2010 omitted to avoid bias of censored data. Graph by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Since 1998 we have monitored 152 color banded birds at Piney Grove including 101fleglings that were banded at Piney Grove since 2000 (remaining banded birds were either translocated birds or adults already present at the site when the banding program began). Despite the production of 101 fledglings over the last decade the population remains relatively young as a whole. Only 49 % of all woodpeckers successfully fledged at Piney Grove since 2000 still remained in 2010. Moreover, nearly half of the currently remaining Piney Grove fledglings were produced within the last two years. Overall, the median time for a fledged bird to remain in the population is only 2 years. Birds missing from the population are presumed to be a result of mortality or dispersal. At the current loss rate, it does not take long for a cohort of birds produced in any previous year to disappear from the population. It is even more apparent that long-term population health requires the constant production and recruitment of new birds.

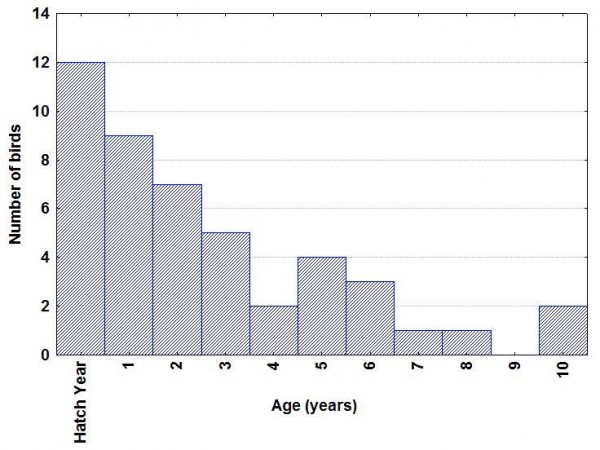

There is however one overriding factor that seems to maintain individuals in the population longer than the 2-year median persistence value and that is breeding opportunity. Birds that have the opportunity to form a breeding pair or take very active helper roles for other breeding pairs persist in the population for longer periods of time. Direct breeding activity increases the median retention time in the population to 6 years. The four oldest birds currently in the population; including two 10-year old birds, an 8-year old, and a 7-year old have all been breeding since 2002 or 2003. Making it past the first two years for these birds is likely a formidable challenge. Acquiring a breeding slot at the Piney Grove after that benchmark is not a matter of age however because birds generally become breeders by their third year and hang on to that slot until their disappearance.

2010 age structure of red-cockaded woodpeckers at TNC’s Piney Grove Preserve. It’s dominated by younger birds due to high rates of reproduction, but older birds generally represent all breeding individuals. Graph by the Center for Conservation Biology.

The reasons for the longer persistence of breeding birds compared to non-breeding birds may be speculative but fits plausibly into those explained by simple dispersal and mortality. Breeding should be the ultimate goal of any woodpecker as life history theory often revolves around maximizing relative fitness or the number of surviving progeny. Breeding opportunities for woodpeckers are often capped at Piney Grove by the number of birds in relation to the number of available breeding sites. We currently have 42 birds using 8 breeding sites with as many as 7 birds occupying a single site. Most birds have a low probability of acquiring breeding status so are forced to either remain as a helper/ non-breeding bird or leave the comfort of Piney Grove in search of new breeding areas of their own. It is likely that the “will” to breed often aids the final decision for some birds to disperse from Piney Grove in hopes of finding other habitat. What the Piney Grove woodpeckers likely do not know is that comparable breeding habitat is virtually non-existent with only a few patches known that are located over 90 miles away.

Non-breeding birds that remain in the population are likely waiting in line for the next breeding opportunity but are often faced with stiff competition from other individuals. Nonbreeding birds are often subordinate to breeding pairs,are mostly hatch year birds and young birds, and sometimes do not have roosting cavities. Birds without roosting cavities must spend the night “free-roosting” on a tree trunk or limb and are more susceptible to mortality from predation or bad weather.

Management and monitoring of this endangered population of birds is made possible from funding by The Center for Conservation Biology (CCB), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), and the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) through a federal aid in wildlife restoration grant from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS).