Chesapeake Eagles Shift Behavior

Virginia peregrine population continues to climb

January 11, 2023

RCW Cavity Creation Benefits the Surrounding Piney Grove Animal Community

January 11, 2023A bald eagle nest just off the Poropotank River in Virginia in 2003. A nest with two equal young and ample food was a normal scene during this time period. This reflects a golden period during the late 1990s and early 2000s when males had more leisure time to hunt and provide for broods. Photo by Catherine Markham.

By: Bryan Watts

1/11/23

We often think of animal behaviors as static species traits. While some behaviors such as courtship rituals may be stylized and relatively robust over time, other behaviors represent dynamic responses to changing conditions. Such behaviors often offer a window on the tradeoffs that species must confront when faced with change.

Over the past two to four decades, the bald eagle population within the Chesapeake Bay has increased more than 30-fold and has begun to reach capacity along tidal reaches. Over this time, the social environment has changed dramatically as potential recruits into the breeding population have run out of viable nesting space. One of the most fascinating questions about the recovery is how eagle ecology will shift along with this ongoing change in social pressure.

Bald eagle pairs express a distinct division of labor, particularly during the early stages of nesting. Females are larger and behaviorally dominant to males. Females control the nest surface, dictate the cadence of incubation and spend the most time brooding and feeding young chicks. Males follow the lead of the female in terms of maintenance of eggs and young chicks, are the main hunters and providers to the young brood and are responsible for guarding the nest against intruders. Males guard nests by perching either on the nest tree or on a prominent guard perch where they are able to view approaching intruders. As the number of potential intruders has increased over the decades, the male is faced with a tradeoff between staying by the nest to guard or going off to forage in order to provide for the energy needs of the brood.

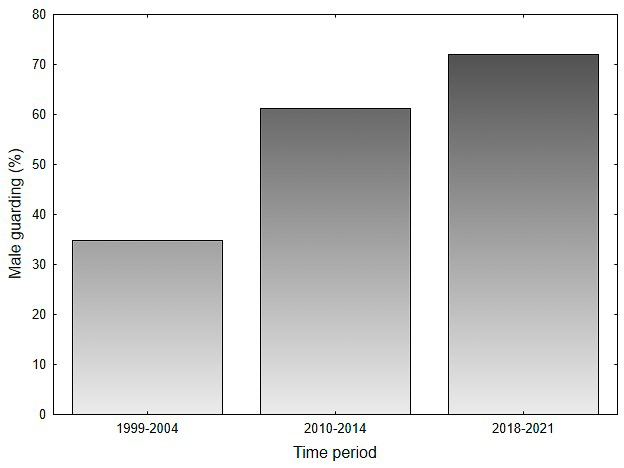

In 1999, while conducting aerial surveys, I began to record information on how many adults were present around active nests. Observations included either no adult, one adult, or two adults present and the position of each adult when present. Over the years I have recorded adult attendance data during three time periods including 1999-2004, 2010-2014 and 2018-2021. The most striking behavioral shift that has occurred over the more than 20-year period is the change in frequency of the second adult in guarding position. During the early period, 34.8% of nests checked had a second bird in guarding position. This increased to 61.3% of nests during the second period and again to 72.1% during the most recent period. This represents a more than doubling of nest attendance by the second adult over the 20-year period.

Shifting time allocation from hunting to guarding has clear implications for the brood. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, we saw no evidence of size asymmetry in eagle broods within the lower Chesapeake. Brood mates were indistinguishable from the air. I can distinctly remember in the late 1990s flying over a nest on the Matoponi River and being shocked after seeing for the first time a brood that was clearly asymmetrical with one large and one small chick. Brood asymmetry is an indicator of food stress and may ultimately lead to food-related brood reduction. Both smaller broods and asymmetric broods have become much more common in recent years.

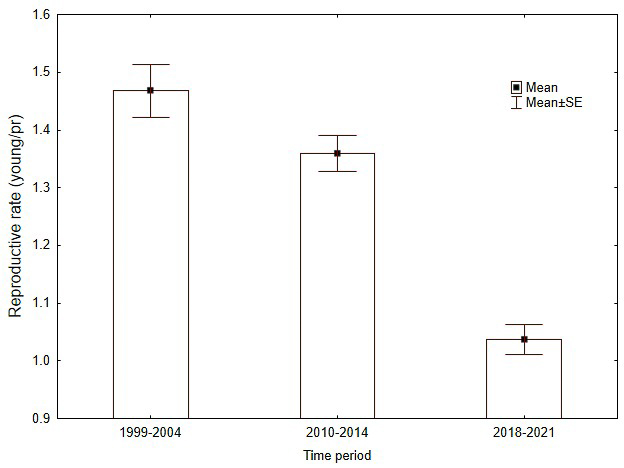

The cost of allocating time to guarding may be seen in the demographic data. Reproductive rate has declined from 1.5 to 1.3 to 1.0 over the time period and the median brood size has declined from 2 to 1. The proportion of breeding attempts that fail have increased from 17.6 to 24.2%, while the proportion of pairs producing 3-chick broods has declined from 13.8 to 5.2%.

Males have responded to increased intruder pressure by allocating more time to guarding nests, but these adjustments have come at a demographic cost as they have been less able to provision broods. However, reductions in productivity will ultimately reduce guarding demands on males by reducing intruder pressure and over time cool an overheated population so that it comes into balance with appropriate space. Male behavior is a sensitive indicator of social stress within the population.