Tracking reveals sexual differences in Ipswich sparrow winter and spring ecology

Nightjar Network to Begin Exciting New Chapter

April 2, 2022

Dos Passos: A conservation legacy

April 7, 2022By: Chance Hines

4/4/22

Spring is in the air and many of our wintering birds are preparing for their annual trip north after enduring the bitterness of winter. For the Ipswich sparrow, this means preparing for a flight to Sable Island, a 27-mile long sliver of land that closely resembles a fingernail clipping discarded into the Atlantic Ocean nearly 200 miles offshore of Nova Scotia. Ipswich sparrows spend their entire life cycle in sandy coastal dunes where their pale plumage perfectly blends with their surroundings. During winter, you are most likely to only catch a glimpse of this species as they run silently through sparsely vegetated dunes along the mid-Atlantic coast.

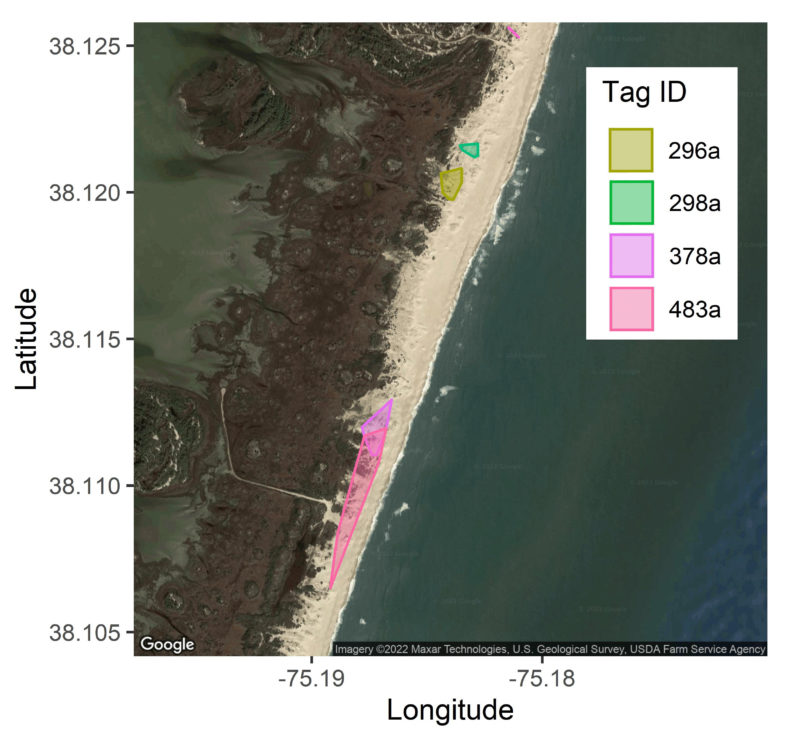

The Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) has studied Ipswich sparrows throughout their winter range since the mid-2000s. Most recently, CCB, in collaboration with Dalhousie University, captured and fitted pencil eraser sized nano-tags on well over 100 birds to understand their movements. Nano-tags emit an intermittent pulse that can be detected using a handheld receiver and Yagi antenna or by a series of over 100 towers in the MOTUS network (https://motus.org/) stationed along the Atlantic coast. We manually tracked individuals on their wintering grounds along Assateague Island to define their home range and thereafter relied on the MOTUS towers to track their migratory path norward.

Our detections showed that Ipswich sparrows take their time returning to Sable Island, usually requiring about a month to reach their breeding grounds. Tracking data suggests that Ipswich sparrows may have difficulty locating their breeding grounds. This is contrary to the typical ease that many bird species exhibit returning to the exact location they were hatched. Ipswich sparrows may have a difficult time navigating their way towards the small sliver of land, sometimes referred to as the graveyard, due to the distance between Sable Island and the nearest mainland coast (109 miles) and the dense fog that frequently blankets the island. This species is one of the only known to attempt the same migratory flights multiple times after abandoning their initial attempt. We have also found, that like many other migratory species, males depart from wintering grounds a couple of weeks before females to set up a breeding territory that will attract a mate. Males typically leave their wintering grounds towards the end of March and females follow a couple weeks afterwards.

CCB has found that sexual differences also exist during the wintering period of the species life cycle. Ipswich sparrows spend approximately 94% of their time in the fore dune and secondary dune, while only occasionally visiting marshes, open beach, and shrubby hind dune habitats. Male Ipswich sparrows are more likely to be located in dunes nearest the ocean while females are more likely to be found in secondary dunes. Males also occupy home ranges that are three times as large as females (2.4 ha vs 0.8 ha). It is not clear what drives this disparity in habitat use and home range size, but sexual differences in food choice could explain some of this.

The primary grass found in dunes along the Atlantic coast, Atlantic beach grass (Ammophila breviligulata), is an early colonizer of dunes and is most productive on the outermost foredune. Beach grass provides particularly thick and densely clumped seed heads during winters following years when storms deposit fresh sand. Often times, you will find isolated bunches of beach grass with thick, full seed heads. Beach grass also occurs further from the open beach in secondary dunes, but plants are less likely to produce seeds in this portion of dune habitat. Males may more exclusively depend on beach grass seeds, which would explain why they spend more time in the foredune and this may require them to search further from territory centers to locate plants with plenty of seeds.

Seaside goldenrod (Solegado sempervirens), poor joe (Diodea teres), and beach primrose (Oenothera deltoides) are plants that are commonly found in secondary dunes and, like beach grass, provide seeds throughout winter. Unlike beach grass, which often forms thick and isolated clumps, these forbs are more regularly spaced. Females may forage on seeds from these plants found in the secondary dunes so that they do not have to search further for productive patches of beach grass.

Undisturbed dune communities like those found along Assateague Island provide both beach grass and forbs, which may explain why Ipswich sparrows are so abundant. However, many portions of dune habitat throughout the Ipswich sparrow range have experienced degradation through coastal development and tropical storms. Hurricane Sandy, for example, devastated dunes along the northeast Atlantic coast in 2012. Beach grass is often planted in efforts to restore these dunes, neglecting other plants that may provide seeds to species like the Ipswich sparrow. In collaboration with Assateague National Seashore, CCB plans to further investigate this issue in the near future and clarify which plants are most important to Ipswich sparrows.