Clutch size in Chesapeake Bay bald eagles: an unexpected history

No good news for eastern black rails in NC and GA

October 4, 2017

A tough year for Chesapeake osprey

October 6, 2017By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

October 5, 2017

There was a time during the late 1800s through the mid-1900s when bird eggs were collected and sold or traded like stamps or coins. During this period, bald eagle eggs were valuable and in demand. The price for a single bald eagle egg was listed as $15.00 in the 1922 American Oologist Exchange Price List of North American Eggs. Due to the general interest in eagles and the value of their eggs, eagle egg collectors were widespread throughout North America. Several major collectors including Harold Bailey, Fred Jones, Edward Court, Richard Harlow, and Willet Griffee were active in the Chesapeake Bay through the 1940s. Each had their own collecting area that seemed to be respected by gentlemanly agreement but all were highly secretive about the location of prized nests where they collected.

Three-egg bald eagle clutch along the upper Potomac River. The Chesapeake Bay appears to have the highest rate of three-egg clutches throughout the breeding range, likely reflecting the high productivity of the area. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Although eagle egg collecting has now gone the way of the stagecoach, compilation of clutch sizes from egg collections provides exciting new insight into the ecology of eagles during a time period before the introduction of DDT into the estuary. Compared to all other accounts throughout the species range, clutch size within the Chesapeake Bay during this early time period was extraordinarily high, averaging 2.46 eggs. In his remarkable book, The Bald Eagle, Mark Stalmaster summarized 16 studies from throughout the breeding range that reported clutch size and indicated that 17% of clutches contained only one egg, and only 4% contained more than two eggs. In stark contrast to this finding, 3.3% of clutches collected in the Bay contained only one egg and 43.0% contained three or more eggs.

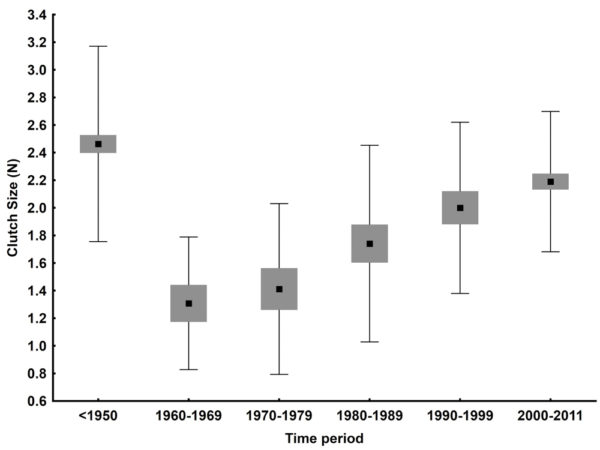

Historic pattern of clutch sizes for bald eagles within the Chesapeake Bay. Clutch size has been increasing since the height of the DDT era and are now approaching those of the collecting boom in the early 1900s. Data from CCB.

Amazingly, eagle egg collections from the Chesapeake included three four-egg clutches and two five-egg clutches. Although rare, four-egg clutches have been documented in recent times within the Chesapeake including three four-young broods. The five-egg clutches are an oddity and have not been reported previously within the bald eagle literature. The clutches were collected by E. J. Court, who was a prolific collector for more than 30 years along the upper Potomac River below Washington, D.C. Examination of the collection notes provides confidence that these clutches were real. The possibility that these clutches resulted from contributions of two females cannot be resolved. Incredibly, the two clutches were collected from the same territory just two years apart. The territory was on the Virginia side of the Potomac in a site known commonly as Crow’s Nest, which continues to be a center of eagle activity to the present day. The circumstances that lead to these clutches are unclear, and because they were collected we are left to wonder if the pair could have hatched all five eggs and raised the young to independence.

Two-egg bald eagle clutch along James River. This clutch size is by far the most common for bald eagles throughout their breeding range. Photo by Catherine Markham.

One of the most surprising discoveries from looking back through the historic clutch record is that bald eagle clutch sizes have changed dramatically over the past century. By the time the aerial survey was initiated in the early 1960s, the average clutch size had been reduced by nearly half compared to the period of egg collecting that closed merely 20 years before. During the 1960s and 1970s, 20 (66.7%) of 30 documented clutches were single eggs and only one (3.3%) contained three eggs. By the 1980s and 1990s, clutches were trending larger with only 26.8% (N = 56) single egg and 16.1% containing three eggs. Although recovery is not complete, after the year 2000 clutches have begun to resemble those in the early 1900s, with only 4.0% (N = 99) single eggs, 66.7% two-egg clutches, and 29.3% three-egg clutches.

The impact of legacy contaminants such as DDT on egg hatching rates, young survival, and even adult mortality from the 1950s through the 1970s has been reasonably well documented. A retrospective assessment of clutch size within the Chesapeake Bay suggests that contaminants likely caused a direct suppression of clutch size as well.