James River eagle recovery enters final chapter

Late arrival and breeding in juvenile-plumaged night herons

July 10, 2017

Crossover Knots

July 12, 2017By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 11, 2017

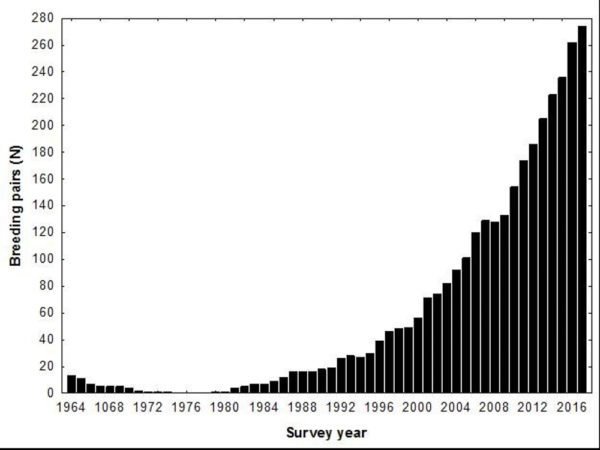

One of the enduring questions in population ecology is: what determines the size of a population? Stated another way: what are the factors that regulate population size? One of the classic approaches of investigating regulatory mechanisms is to study a population over time that has either recently colonized a new habitat or is rebounding from a catastrophic event. Investigating a population that is growing within an effective “vacuum” allows us to observe its behavior as it increases and approaches capacity.

Eagle brood along the James River in the early 2000s during the peak in productivity. Photo by Bryan Watts.

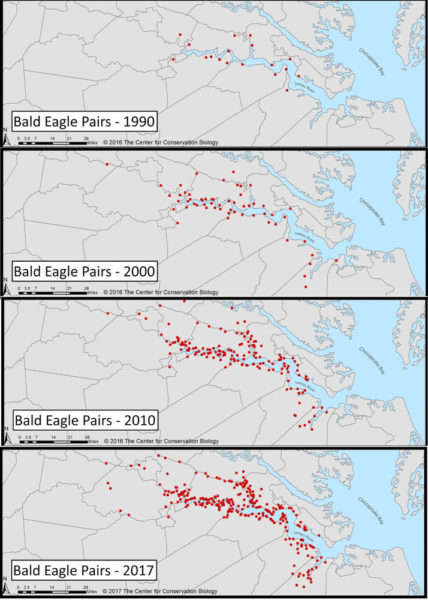

During the height of the DDT crisis, the James River supported no breeding bald eagles for a period of five years during the 1970s. The once-thriving population was diminished as productivity sank to levels below that needed to offset adult mortality. Over an 11-year period during the 1960s and early 1970s, eagles on the river produced only three young. After DDT was outlawed in the United States, the James River was recolonized by breeding eagles and productivity rose through the 1980s, leading to dramatic population growth. Annual surveys have documented the phenomenal recovery that continues through the 2017 breeding season. The breeding population has experienced tremendous momentum over recent decades, increasing from 18 pairs in 1990 to 57 pairs in 2000 to 272 pairs in 2017.

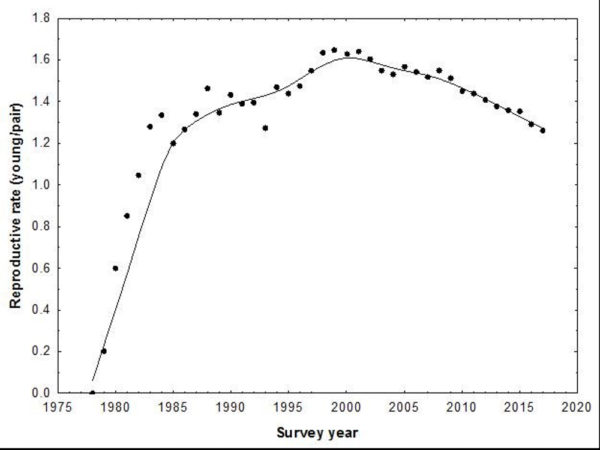

Long term pattern of productivity for bald eagles breeding along the James River in Virginia. Productivity appears to have reached a peak during the late 1990s and has gradually retreated since that time. Data from CCB.

As we have witnessed the population advance every year since the late 1970s, the central questions remain: How high will the population rise and what are the underlying regulatory mechanisms that will constrain it? Although the population continues to increase, the long-term trend in productivity gives the first real signal that we have entered the last chapter of the recovery. The average number of young produced per breeding pair reached a peak during the late 1990s and has shown a gradual decline since this time. The rate has now contracted back to levels not seen since the 1980s. The continued decline of productivity back down to or near maintenance levels is the demographic response that will ultimately constrain the population and bring it to some form of equilibrium.

Maps illustrating the recovery of breeding bald eagles along the James River in Virginia. Data from CCB.

Why is productivity declining? The recovery in productivity throughout the 1980s and 1990s drove exponential growth in the breeding population. Beginning in the late 1990s, actual growth of the population began to diverge from that expected based on the number of young produced. This divergence created an increasingly large population of floaters (breeding-age birds that do not hold territories) setting up a class war between the haves and the have-nots. We believe that the disruption of breeders by floaters represents the negative behavioral feedback that is pulling down productivity and will ultimately bring the population into equilibrium with available breeding space.

Long term survey data documenting the decline and recovery of breeding bald eagles along the James River in Virginia. Data from CCB.