Conservation in conflict: peregrines and shorebirds in the mid-Atlantic

Grace Still at TRS July 3, 2016

July 4, 2016Black-bellied plovers complete annual cycle

July 7, 2016

The outer coast of the mid-Atlantic region has become an important site for the conservation of both breeding peregrine falcons and migratory shorebirds. The region is a terminal, spring staging area where several shorebird species stop for an extended stay to build fat reserves for their final flight to arctic breeding grounds. The region has served this role for thousands of years and includes designated Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserves with both “hemispheric” and “international” status as well as many conservation lands dedicated to shorebird protection. The region is also the site where, during the 1970s, a decision was made to establish a breeding population of peregrine falcons to advance the cause of peregrine restoration in eastern North America.

A male peregrine hands off a shorebird to the female on top of a skyscraper in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Males do most of the hunting during the brood rearing period and small shorebirds fit perfectly into their prey size range. Photo by Reese Lukei, Jr.

The eastern peregrine falcon was a casualty of the DDT era. With no alternatives, the recovery team decided on a bold plan to stand up a captive breeding program and release birds into the wild. After some experimental releases a fateful decision was made in 1975 to release birds on the outer Coastal Plain, a geographic area with no natural cliffs for nesting and no historic breeding population. The hope was that a breeding population would be established that would ultimately colonize the historic Appalachian breeding range. Between 1975 and 1985, 307 captive-reared peregrines were released on the Coastal Plain (VA to NJ) on artificial towers. A breeding population was rapidly established that has blossomed to more than 70 pairs (read more about establishment of the coastal breeding population). All of these pairs nest on man-made structures.

Female peregrine taking a ruddy turnstone into a nest box to feed young. Females typically take care of the nest site and feed the brood.

Migratory shorebirds make up the bulk of the prey used to feed peregrine broods on the outer coast and peregrines have adjusted their breeding season to capitalize on staging shorebirds. Two independent studies of diet including one in Virginia and one in New Jersey have shown that shorebirds account for more than 70% of the prey used to feed young. As the peregrine population has grown over the past 30 years, the annual take of staging shorebirds is now estimated to be several thousand. Several shorebird species seem to receive the most attention including dunlin, short-billed dowitcher, black-bellied plover, willet, and some red knots. A sample of video footage from 2016 on one pair for seven days included 12 dunlin, 4 semipalmated plover, 1 American oystercatcher, 1 willet, 1 black-bellied plover, 1 ruddy turnstone, 1 short-billed dowitcher, and 1 spotted sandpiper.

Collection of video clips from a trail cam placed in 2016 on one of the peregrine nesting towers in coastal Virginia. The clips show selected shorebird deliveries. Viewers may readily recognize dunlin, semipalmated plover, ruddy turnstone and willet.

The establishment of a robust breeding population of peregrine falcons within one of the most significant shorebird staging sites along the Western Atlantic Flyway represents a conflict between opposing conservation objectives. Of the 35 shorebird populations that use the flyway, 65% are declining. Some believe that the establishment of the peregrine breeding population may be contributing to these declines. For some shorebird species, the estimated take by the peregrine population may approach sustainable mortality limits (read more about sustainable mortality limits for shorebirds), suggesting that the population may be contributing to declines.

Shorebird legs collected from two peregrine nest boxes along the Delmarva Peninsula of Virginia. Peregrines take several species of shorebirds during the spring staging period. Photo by Bryan Watts.

One possible management solution may be to translocate young peregrines from the outer coast to the mountains for release. The Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries, the National Park Service and CCB have had a long-term partnership of moving birds to mountain hack sites (read more about this hacking program). The focus of this program has been to re-establish breeding falcons within the historic mountain range while increasing the survival of young peregrines reared in hazardous locations. A third objective of moving birds from the outer coast would be to provide relief to migratory shorebirds by greatly reducing the number of mouths to feed.

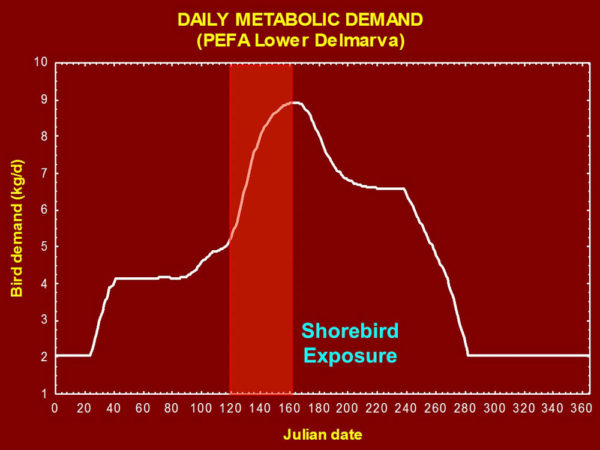

The newly established peregrine breeding population has adjusted its breeding season to capitalize on the spring passage of shorebirds. Data from The Center for Conserv

The win-win-win program of moving young peregrines to the mountains would mitigate some of the conservation conflict between breeding peregrines and staging shorebirds. A modest amount of funding is needed to expand the hacking program to accommodate the young peregrines.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 6, 2016