Mexican whip-poor-will monitoring

Camellia & Yellow-Crowned Night Heron

July 10, 2010Rare four-chick eagle brood in Pennsylvania

July 11, 2010

Written by Michael Wilson

July 10, 2010

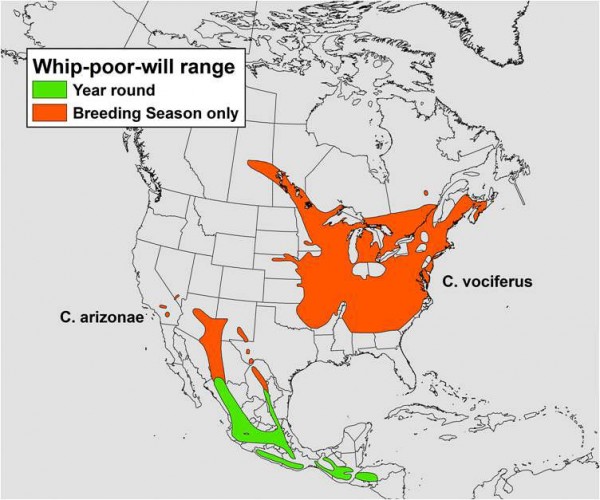

In the 51st supplement of the AOU Checklist released in 2010 the whip-poor-will was taxonomically split into the eastern and Mexican species (Caprimulgus vociferous and C. arizonae, respectively). There has always been a long standing tradition of recognizing the eastern and Mexican whip-poor-wills as unique populations based on their distinct geography, vocalizations, plumage, morphology and other characteristics. This population-level recognition has benefitted both species because each has undergone decades of regionally-focused conservation. This divided attention also serves as a reminder of the importance of recognizing distinct populations of other species that have multiple forms in the conservation planning process.

Figure 1. Breeding and year round distribution for the geographically isolated populations of the Mexican (Caprimulgus arizonae) and Eastern (C. vociferous) whip-poor-wills. Map by the Center for Conservation Biology.

The Mexican whip-poor-will breeds throughout Mexico and in the Southwestern United States including western Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Nevada. In the U.S., the Mexican whip-poor-will is associated with high elevation pine-oak, pinyon juniper, and ponderosa pine forests. These habitats are generally found above 1,500 m altitude and are limited in distribution by the interaction of climate and elevation. The warmer temperatures found at lower elevations create a natural barrier to the down slope movement of these coniferous forest types, while elevation places a cap on the potential land area available to support these habitats and populations of Mexican whip-poor-wills. Climate change and land use change threatens to reduce the available habitat in these areas through possible replacement of higher elevation coniferous habitats with those unsuitable for Mexican whip-poor-wills. The reconfiguration of habitats predicted from climate change could likely result in dramatic population reductions for this species.

The U.S. Nightjar Survey Network was initiated by the Center for Conservation Biology in 2007, as a program to collect and analyze population trend data for whip-poor-wills, chuck-will’s-widows, common poorwills, lesser nighthawks and their nightjar relatives. With the help of volunteers and biologists from the southwestern United States we have been able to focus some of the monitoring effort specifically for Mexican whip-poor-wills.

Mexican whip-poor-will in South Fork, Cave Creek Canyon, Arizona. Photo by Chris West.

We are in the process of developing a “best effort” approach to monitoring the species. The high elevation areas of the southwestern U.S. set a natural survey frame for choosing areas to monitor for this species. We used GIS-based habitat models created by the Southwest Regional Gap project that identify suitable high elevation forests for Mexican whip-poor-wills and reviewed historical records to form the border of survey areas. We currently have 37 of the 147 nightjar survey routes in Arizona and New Mexico placed in the identifiable life zone for Mexican whip-poor-wills and also have additional routes appropriately placed in other states. We will be supplementing any additional sampling effort with a spatially balanced location method while also contending with practical limitations such as road access and habitat cover.

View along a forest road within the Blue Wilderness Area of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest of Arizona. Mexican whip-poor-wills have been detected by the U.S. Nightjar Survey Network along this road. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Mexican whip-poor-wills have been suggested by others to be hard to detect during surveys, but as we expected, data collected by Nightjar Survey volunteers show that this species is reliably discovered when surveyed during bright moonlit nights. Mexican whip-poor-wills were detected on four survey routes in Arizona and one route in California. Because the detection history of each individual bird is recorded by volunteers in one minute intervals, we are able to determine that Mexican whip-poor-wills have a 96 % detection rate during any one minute interval of the total six minute counting period at a route stopping point. There is also an equal probability of detecting that same bird again in any subsequent minute of survey while at the same point. This relatively high level of detectability was not surprising to us and matches detection rates of eastern whip-poor-wills counted on other routes of the U.S. Nightjar Survey Network. Whip-poor-wills are boisterous birds and have been known to repeat their onomatopoetic call over 10,000 times during a full moon night.

Focal survey area (as a hexagonal cell grid) of the U.S. Nightjar Survey Network used to monitor the population of the Mexican whip-poor-wills in Arizona and New Mexico. Map by the Center for Conservation Biology.

The special focus we are placing on monitoring Mexican whip-poor-wills is only possible with the help we have received from southwest regional biologists, including Carol Beardmore of the Sonoran Joint Venture, Dave Kreuper of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Christopher Rustay of the Playa Lakes Joint Venture, and James Schroeder of the U.S. Forest Service. These folks have been instrumental in the continuing route selection process, organizing volunteers, and even conducting surveys. We also thank the many volunteers in Arizona such as Shawn Caroll, Janine McCabe, Greg Clark, Elaine and Bob Hugh, Richard Inman, Tom Hildenbrandt, Cathryn Wise and Sandra Remley in California (who identified a new location for Mexican whip-poor-wills during a nightjar survey there) for adopting routes within focal areas of Mexican whip-poor-wills that are often remote and relatively more difficult to access.

Project sponsored by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB).