CCB Surveys Reveal Wayne’s Warbler Strongholds in Virginia

CCB and Partners Supporting Whimbrels Through Coordinated Conservation

October 9, 2024

The Arc of Conservation

February 5, 2025By: Chance Hines

9/24/24

The majority of old-growth swamps of Virginia and other mid-Atlantic states have been lost to logging and development, but the remaining fragments of these swamps still provide critical habitat for a variety of taxa protected under the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA). Included among these rare and sensitive taxa are several plants, the Dismal Swamp southeastern shrew, and the red-cockaded woodpecker.

Among these fragmented habitats, another species has recently garnered attention for potential ESA protection: Wayne’s black-throated green warbler. While most black-throated green warblers breed in forests across northern states, southern Canada, and the Appalachian Mountains, Wayne’s warblers are restricted to swamps and adjacent forests in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. This form was likely more widespread before extensive timber harvesting destroyed much of the mature forest it once inhabited, but it wasn’t well-described until after much of this habitat was lost. In addition to breeding in a disjunct area, Wayne’s warblers are smaller and have different migration patterns than their nominate relatives. A recent study confirmed that Wayne’s warbler is genetically distinct, and coupled with evidence of a continued population decline, efforts have begun to petition for its protection under the ESA.

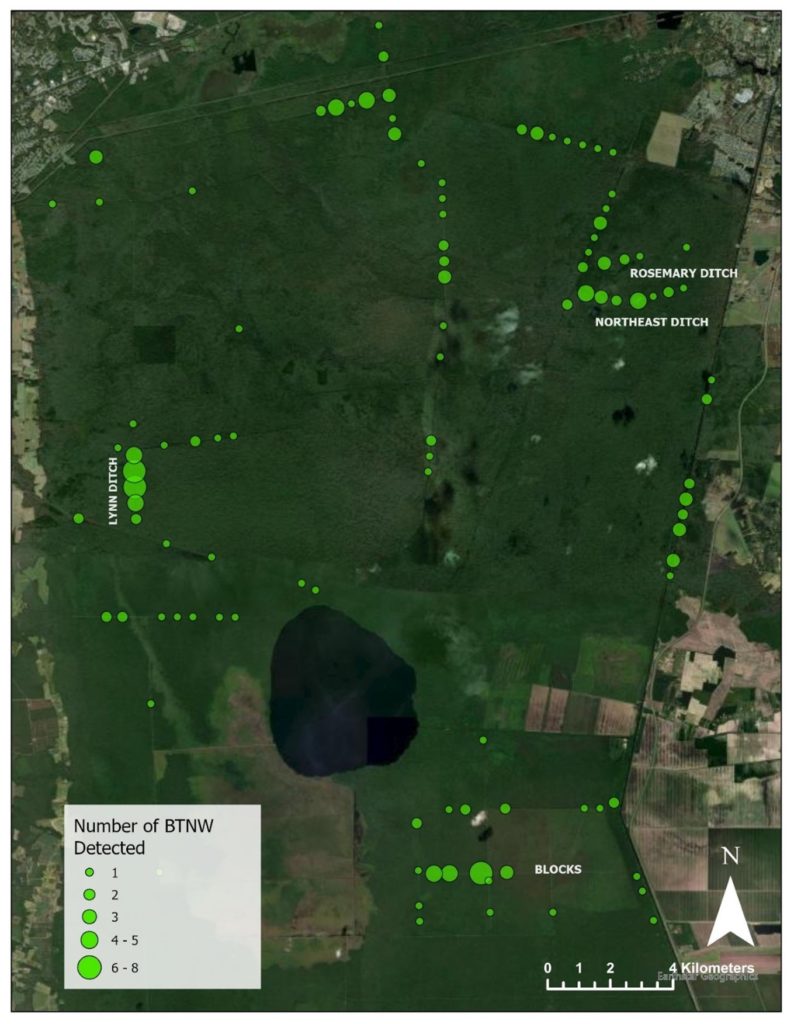

In partnership with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, CCB conducted a survey for Wayne’s black-throated green warbler during the 2024 breeding season at Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, historically their stronghold in Virginia. This effort coincided with similar surveys in North Carolina. The Virginia survey was highly successful, with the warbler observed at 35.2% of the 298 survey points. Our findings indicated that the birds were more likely to be present in areas with greater canopy closure, less shrub cover, and higher above-ground forest carbon, which we used as a proxy for forest age. We observed relatively high concentrations of the warblers in several locations, leading us to focus on these spots for more intensive monitoring. Some of these areas, such as the Great Dismal Swamp Canal Trail and the Washington Ditch trailhead, are easily accessible for birding.

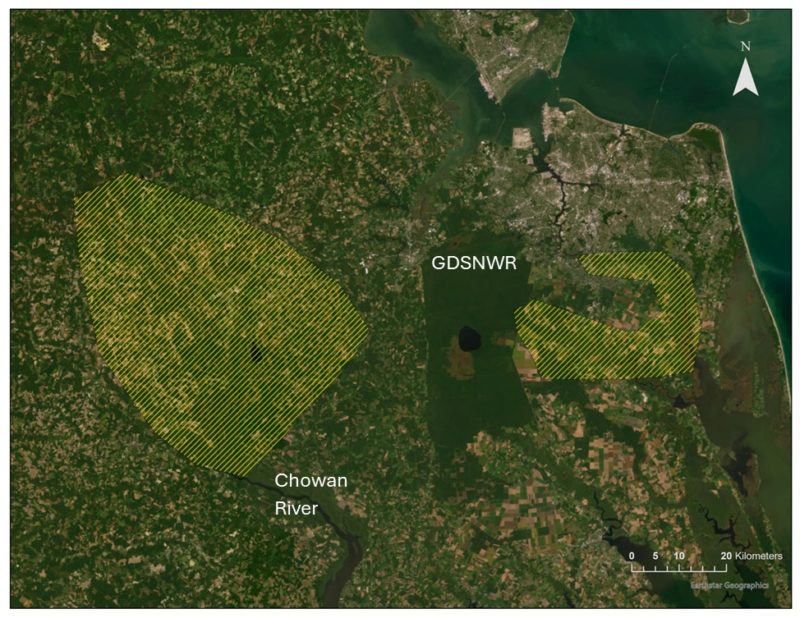

In contrast, survey efforts in North Carolina were less successful, with Wayne’s black-throated green warbler detected at only three of 173 locations in potential habitat. This aligns with the belief held by some biologists that the species has been declining in the more southern states. However, the 2024 surveys did not include Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, which CCB identified in the early 2000s as potentially supporting the densest population of Wayne’s warblers.

While the species appears to be declining in the southern part of its range, it seems to be holding strong in Virginia, particularly within the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. The warbler’s preference for older, mature forests makes sense in this context, as the refuge includes large areas that were logged in the past, starting with efforts led by George Washington and the Great Dismal Swamp Company. These forests have since reestablished and begun to mature since they were last logged, suggesting that the habitat quality within the refuge may continue to improve as the forests age further. What remains unclear is the species’ distribution outside of the Great Dismal Swamp. Next year, CCB will survey the tributaries of the Chowan, North Landing, and Northwest Rivers to gain a clearer picture of this distribution. Above-ground carbon signatures, which were associated with occupied locations at the refuge, are particularly high along difficult-to-access sections of the Northwest River that were difficult for loggers to access. We hope these forests will also support warbler populations.