The 2024 Osprey Field Season

Adult turnover spikes in Virginia peregrines raising alarms about the potential impact of avian flu

July 18, 2024

Recent Literature published by CCB

July 18, 2024By Bryan Watts

7/13/24

Like blue crabs and salt marshes, the osprey is interwoven into the fabric of the Chesapeake Bay culture. Many generations of Bay residents have grown up with the sound of osprey calling overhead and each winter wait with anticipation for their return in early spring. During the summer months, watermen and many waterfront homeowners live with osprey on a daily basis and have become intimately familiar with their nesting ecology. Osprey have contributed a great deal to the quality of life for people around the Bay, and in return residents have erected thousands of private nest platforms that have played a role in population recovery.

CCB has worked with osprey in the lower Chesapeake Bay since 1970 when Mitchell Byrd and graduate students began to map pairs and monitor breeding performance. The efforts were prompted by global declines driven by DDT and other contaminants. Large efforts to monitor osprey within the Bay would continue to the early 1990s when the population was declared “recovered.” CCB’s work with osprey after 1990 has been mostly focused on ecological shifts in the growing population and management.

Several years ago, we began to be contacted by residents and watermen throughout the main stem of the Chesapeake who were concerned about “their” osprey pairs and the lack of chick production. As the contacts began to mount, we agreed to investigate. Over the past three years we have monitored osprey productivity within a portion of the lower Bay, examined diet and performed a food supplementation study. We have also compiled historic data and compared past patterns to the present in Mobjack Bay. We have shown that productivity has declined within Mobjack Bay to unsustainable levels, that the decline observed is due to food stress and that menhaden abundance within Mobjack Bay in recent years is inadequate to support a stable osprey population.

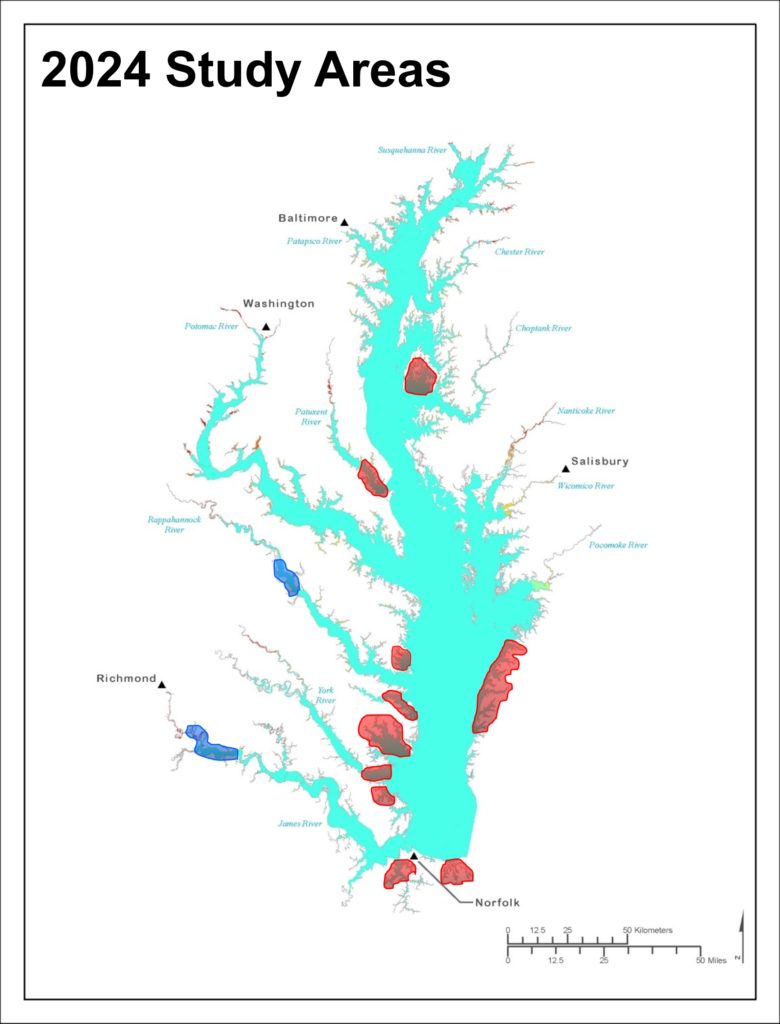

Following the recent work by CCB in Mobjack Bay, an ongoing question is – Are osprey experiencing similar problems in other parts of the Bay? During the 2024 breeding season we have expanded work beyond Mobjack to include 12 study areas, including 10 study areas in the higher salinity (>10 parts per thousand salinity) portions of the Bay and 2 study areas in tidal fresh waters. Within these study areas we have been monitoring more than 600 pairs of osprey. Our objectives during the 2024 season include 1) evaluating spatial variation in osprey breeding performance (demography) throughout the Bay, 2) investigating diet and brood provisioning throughout the Bay and 3) beginning to investigate the hunting performance of male osprey. To measure breeding performance, we have been monitoring osprey pairs within study areas since early March. To quantify diet and provisioning, we have placed around 50 trail cameras on nests within study areas and to begin to understand male hunting performance, we have been creating time budgets for males within several territories.

The 2024 breeding season has been unusually long and is continuing. As the season winds down, we will compile summary statistics for each study area and report the results in August. We have begun to review photos from nest cameras and will be working on resulting diet information over the next several months, so stay tuned. During the 2024 nesting season, CCB has been joined by biologists from the United States Geological Survey (covering the lower Choptank River on the Eastern Shore of Maryland), the Virginia Aquarium (helping to cover the Lynnhaven River), the Maryland-National Capital Park (helping to cover the lower Patuxent River) and the Elizabeth River Project (helping to cover the Elizabeth River). We thank all of these biologists and their respective agencies/organizations for their tremendous efforts.