A tale of two bays: Osprey fortunes diverge

Recent literature published by CCB

July 8, 2023

Peregrine Hacking Program Stands Down within Shenandoah National Park

July 8, 2023By: Bryan Watts

7/5/2023

Over the past few years, I have received questions from homeowners, watermen and keen observers around the lower Chesapeake Bay about osprey. Waterfront homeowners have been concerned about “their” pair (often nesting on a private platform). The watermen who have spent their springs out on the water for decades have been concerned about many pairs within the area where they work. The questions are generally the same. What is happening with the osprey? Why are they not producing any young? Nearly all of these inquiries have come from the main stem of the lower Bay. These are the salty polyhaline (above 18 parts per thousand salinity) areas of the Bay where osprey have historically depended on menhaden as their primary prey. Our observations over the decades suggest that the homeowners, watermen and general observers have legitimate reasons for concern.

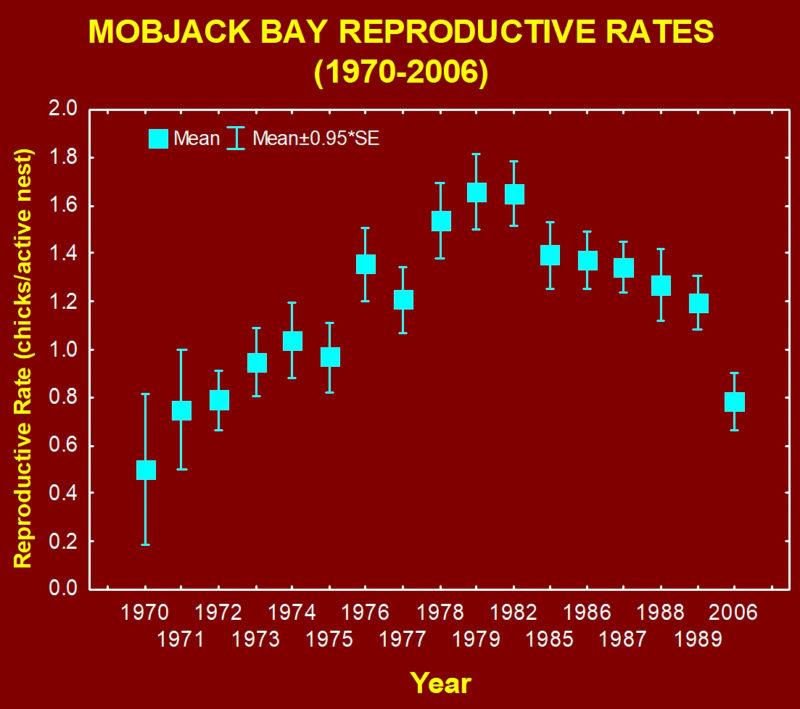

One of the most prominent subestuaries of the lower Chesapeake is Mobjack Bay. We have osprey productivity data for this area dating back to 1970. Mitchell Byrd and a list of his graduate students including Bob Kennedy, Gary Seek, Chris Stinson, Tim Kinkead and Peter McLean monitored osprey within this location from 1970 through 1990. Monitoring shows that reproductive rate rises from the DDT era to a high in the early to mid-1980s and then begins to decline toward 1990. My graduate student, Andy Glass, worked in Mobjack during the 2006 and 2007 nesting seasons. More recently, Michael Academia worked in Mobjack during the 2021 nesting season. By 2006 productivity had declined to 0.75 young/pr or equivalent to rates documented prior to 1975. By 2021 productivity had declined to 0.32, a rate lower than any year since 1970.

The underlying cause of reproductive failure in Mobjack has shifted from the DDT era to the present. In 1972, the hatching rate of eggs was 36.5%. Gains in productivity from the early 1970s through the mid-1980s was driven by an improvement in hatching rate as the population recovered from DDT. By the late 1980s, hatching rate was above 90% and in 2006 hatching rate was nearly 95%. Declines in productivity after 1985 have been driven by the starvation of young in nests after hatching. Between 1975 and 2006 fish delivery rates to nests dropped by more than 50% and the importance of menhaden in the diet also dropped by 50%. For most pairs, fish availability in Mobjack Bay is not adequate to raise even a single young. The study conducted in 2021 demonstrated that experimental supplementation of nests with menhaden was effective in reducing starving rates and driving productivity above maintenance levels. This result suggests that if the menhaden population was allowed to recover, osprey could return to sustainable reproductive rates.

My response to homeowners, watermen and concerned osprey watchers about the lack of young in nests around the lower Bay is that the current fish availability is not high enough to allow osprey to reproduce sustainably. Their young are starving in the nest – most within the first week after hatching.

One of the added questions that homeowners and other observers have is, “Is this just a problem with my pair or is this more widespread?” On the broader population level, the question is, “What is the geographic extent of the demographic sink or black hole?” To begin to address this question, we conducted some broader surveys during the spring of 2023 to expand our view. We surveyed three polyhaline areas of the Bay including Mobjack Bay (Ware River, North River, East River), the lower York River and the Lynnhaven River. The findings were both shocking and depressing. Of the collective 167 nests monitored, only 17 were successful producing 21 young. The reproductive rate of 0.33 is less than 30% of what is needed for the population to break even.

For contrast to the polyhaline reaches, we surveyed two study areas that fall on the other end of the salinity spectrum, the tidal fresh. Tidal fresh reaches of the Bay are located near the fall line on the inner Coastal Plain, have large fresh water inputs and support a different fish community. Within these reaches of the Bay osprey depend on catfish, gizzard shad and other assorted fish species rather than menhaden. The two study areas included the upper James River (Weyanoke Point to Dutch Gap) and the upper Rappahannock River (Hoskins Creek to Toby’s Point). We checked a collective 91 nests within this salinity zone. Seventy-three nests were successful, producing 133 young or a reproductive rate of 1.46 young/pair. This productivity is nearly 4.5-fold higher than what was observed within the high salinity reaches.

Osprey productivity within these different areas of the Bay has diverged in recent decades. Osprey within the tidal fresh reaches of the Bay are reproducing at sustainable levels while those within the polyhaline reaches that we have sampled so far are reproducing at extreme deficits. The deficit is being driven by fish availability with the key fish species being menhaden. Harvest policy and rates over the past three decades have not allowed stocks to recover to levels required by osprey to successfully reproduce.

These preliminary and limited surveys suggest that the geographic area in which osprey are demographically under water is large and possibly growing. Some key questions within the broader Bay population are, “Are the other osprey breeding areas large and productive enough to offset the deficit within the black hole?” and “What is the spatial extent of the black hole?” In 2024, we will expand our coverage area in an attempt to define the edges of the demographic sink and we will cover a larger portion of the Bay to assess whether or not the productive areas are capable of sustaining the broader Bay population.