Divergence in Virginia Peregrines

Management Guidance for Eastern Black Rail

March 29, 2023

Saltmarsh Sparrows Surviving Virginia’s Winter Weather

March 29, 2023By: Bryan Watts

3/27/23

Following the complete extirpation of peregrine falcons in eastern North America during the DDT era, the eastern peregrine recovery team made the bold decision to build a captive breeding program that could produce the young falcons needed to re-establish the breeding population. The effort was driven by Tom Cade of the Cornell Lab. The breeding stock used for the captive program was of mixed heritage and contained individuals from non-indigenous subspecies (F. p. cassini, F. p. brookei, F. p. pealei, F. p. peregrinus, F. p. tundrius, and F. p. macropus), as well as native F. p. anatum. The program was successful and between 1978 and 1993, 242 captive-reared falcons were released in Virginia. The captive team maintained meticulous records on ancestry and productivity including the timing of laying and hatching.

Since the first successful nesting in 1982, the breeding population of peregrine falcons in Virginia has expanded in both size and geographic distribution. During the 2022 breeding season, Virginia supported 34 known breeding pairs nesting throughout the Coastal Plain, Piedmont and mountains. Breeding continues to be concentrated on the outer Coastal Plain with more than one third of the known state population nesting on the Eastern Shore.

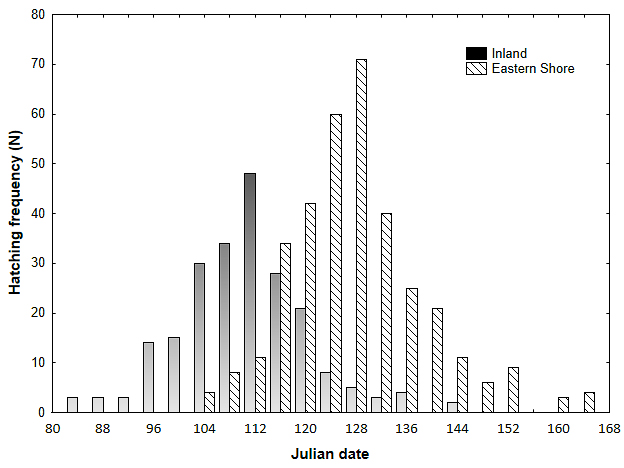

One of the more intriguing aspects of population establishment has been the realization that the timing of nesting has shifted over time and between geographic areas. The mean hatching date for all captive-reared birds released in Virginia was April 29th. Over the past several years the mean hatching date for inland pairs has been April 21st and the mean hatching date for pairs on the Eastern Shore has been May 6th. Hatching date for inland and Eastern Shore broods have shifted away from the captive stock and are now 14 days apart. Inland pairs are now nesting significantly earlier than pairs on the Eastern Shore.

The timing of nesting in most birds is a pliable trait that is adjusted to maximize the production of young. Many species with unpredictable episodic food sources are opportunistic breeders that will nest whenever food availability allows. For species like peregrines with predictable, seasonal changes in prey availability, nesting is timed to match the greatest food availability with the greatest food demand by the brood. Divergence in laying and hatching dates between the Eastern Shore and inland areas reflect adjustments to take best advantage of local prey populations.

Pairs of peregrines nesting on the Eastern Shore raise broods primarily on migrant shorebirds that stage in the spring on their way north to Arctic breeding grounds. These species, including short-billed dowitchers, ruddy turnstones, black-bellied plovers and red knots, reach peak numbers during the second and third weeks of May. Hatching young in early May allows pairs to take advantage of the large numbers of shorebirds staging during the coming weeks.

Shorebirds are much less available in inland areas and pairs of peregrines within these areas raise broods on large passerines including among others common grackles, blue jays and common flickers. The timing of nesting relative to these passerines is not completely clear but may reflect an advantage for taking these birds while they are concentrated within the region before they migrate north (common flickers) or while they remain in flocks before dispersing into pairs for their own breeding.

Across just a small number of generations, peregrine falcons have re-established themselves in Virginia and adjusted to local conditions. These adjustments have included a shift in breeding phenology to take full advantage of the seasonality of important local prey populations. We should expect continued adjustments that allow pairs to exploit local opportunities.