Eagles and Muskrats

Recent Literature from CCB

April 7, 2022

The osprey man of Tilghman

July 7, 2022By: Bryan Watts

6/29/22

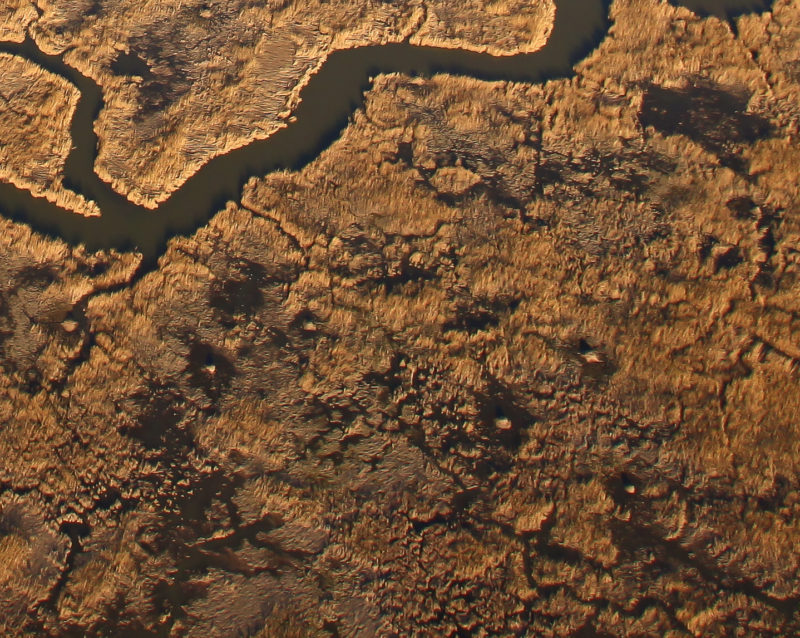

We turn south onto Occupacia, one of the most productive creeks along the Rappahannock. Ducks rise up in waves ahead of us leaving plumes of mud dotted in the shallows. The creek meanders through lush fields of winter wheat – stalks rippling with the wind – moving the surface like an emerald river. As we reach the end of open water which disappears into marsh, the plane throttles back and settles into a glide toward a lone pine. We dip low over the nest and the female is incubating but fast asleep with her head down. In the nest beside her is the distinct auburn hair of a muskrat glowing in the sunlight. The scene captures one of the great ecological linkages in the Chesapeake Bay – marsh, muskrat and bald eagle.

Muskrats are widespread and use a range of aquatic habitats in Virginia. In 1950 and 1951, as a master’s student at Virginia Tech, Mitchell Byrd studied the workings and economics of the muskrat industry in Virginia. To assess how the industry operated within different parts of the state he chose study areas that included a creek (Stroubles Creek on the Tech campus) in the mountains and a brackish marsh (Island Farm Marsh on the Rappahannock just below Occupacia Creek) in the Bay. Muskrat ecology shifts between the Bay and the mountains. Muskrats along mountain streams dig burrows in stream banks while muskrats in the large brackish marshes live in houses built with marsh vegetation. Muskrat populations reach higher densities within the large brackish marshes and this difference influences the economic return for trappers. Byrd found that trappers in the mountains made $0.75/hour of work compared to $2.60/hour in Island Farm Marsh.

Population density has an influence on where eagles most often use muskrats as prey. I have walked into eagle nests for many years to collect prey remains after the nesting season. Muskrat skulls are most likely to be found around nests that occur within a specific salinity band along the James, York, Rappahannock and Potomac rivers that support brackish marshes. Eagles use a short list of mammals in the Bay that includes rabbits, gray squirrels, opossums and small raccoons. It is no accident that muskrats are by far the most frequently used mammal. They are wholly aquatic, and unlike beavers and otter are small enough for eagles to handle. In all of the years collecting prey remains I have found only one beaver skull and it was from a pup. Although eagles take a large number of muskrats, their take is mostly concentrated along the brackish marshes.

For many decades the eagle’s taste for muskrat put them at odds with the fur trapping community. Soaring over the marsh, eagles can easily see captured muskrat and come down to steal or feed on them. While visiting eagle nests along the James River in 1935, Bryant Tyrrell met with a Mr. Moore near Hopewell who told him that he used to trap many muskrats in the area but it was no longer practical due to the number lost to eagles. Tyrrell later talked with Mr. C. W. Doughtery of Claremont who ran a line of several hundred traps and was told that eagles destroyed as many as ten muskrats per week at a loss of $1.50 each. Many of the trappers shot eagles that came down into the marshes and Mr. Doughtery described the normal practice of setting several traps around a damaged carcass that would often result in catching the eagle when it returned. As the bottom fell out of the fur market during the 1980s, many trappers seemed to lose interest in muskrats and the conflict appears to have subsided or is not discussed openly.

Muskrats are not the only prey that attracts large numbers of eagles to the brackish waters of the Bay. Spring spawning runs of shad, blueback herring and alewife may be the largest draw. But there is something about seeing muskrats in eagle nests that completes a puzzle. Eagles and muskrat fit together here in the Bay. Seeing them together is a sign that things are as they should be.