Barn owl blues

CCB team spends fifth spring with red knots along South Atlantic Coast

September 23, 2019

Whimbrel AJK returns to Aruba

September 30, 2019By Bryan Watts

9/30/19

Few experiences take us back to the Halloweens of childhood like climbing up into a silo or hayloft at night and hearing the hissing and bill claps of a barn owl brood echoing off the walls. Once reaching the brood, they perform their monster sway in unison. In coastal Virginia, these sights and sounds have become increasingly rare as nesting pairs have continued a more than sixty-year slide.

A brood of barn owls demonstrate their defense behaviors along the seaside of the Delmarva Peninsula. The outer coastal bays are the last remaining stronghold for the species in coastal Virginia. Video by Bryan Watts.

The common barn owl is one of the most widely distributed bird species in the world and occurs throughout the Americas, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. The species requires open grasslands to hunt. Following the Civil War, land clearing reached a climax throughout eastern North America both to expand agricultural lands and to harvest wood products. Several species of grassland birds, including barn owls, expanded into this breach and established successful breeding populations. However, the fortunes of these birds would begin to shift dramatically by the 1950s when farming practices began to intensify and idle lands were reforested. During the grassland heyday, barn owls were widespread and common in Virginia. Like most other areas in eastern North America, the Virginia population has experienced a slow but steady decline stretching back for several decades.

Chuck Rosenburg, a graduate student of Mitchell Byrd’s, worked with barn owls throughout Virginia in the 1980s and documented more than 110 breeding territories across the state. During the 1980s and 1990s we established more than 100 nest boxes and trays to facilitate breeding throughout all physiographic regions in Virginia. None of the nesting sites in the Coastal Plain known to Chuck during the 1980s are still active today. As recently as the 1990s, barn owls nested in offshore duck blinds on the James, York, Rappahannock, Potomac, and Back Rivers and foraged within adjacent farmlands or marshes. These populations have now collapsed. Today, the only consistently used areas of the Coastal Plain are the outer coastal bays including Back Bay and the Delmarva Seaside.

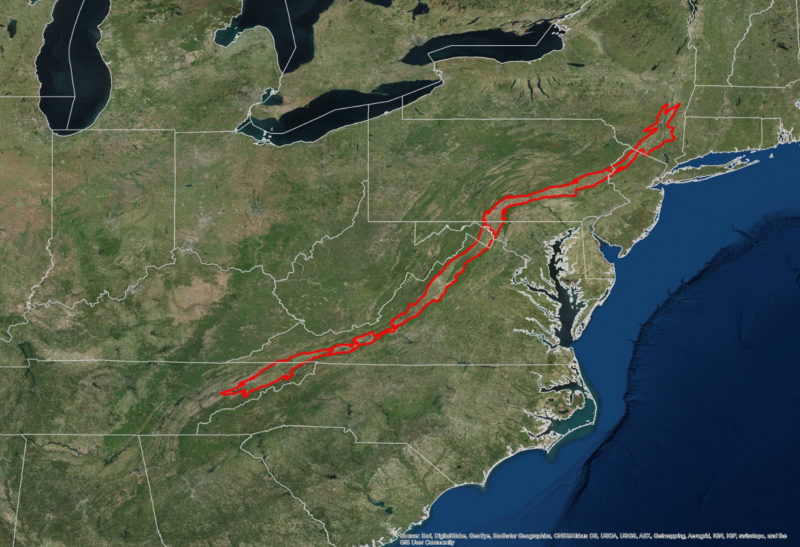

Today, the bright spot for barn owls in Virginia continues to be the Shenandoah Valley or the Virginia portion of the Great Valley. The Great Valley is a series of lowlands stretching from Quebec to Alabama and represents one of the major land features of eastern North America. The valley was a significant north-south travel corridor in prehistoric times. The central valley (stretching from Tennessee to southern New York) continues to be an important agricultural area supporting both crop and livestock production. Due to the continuing focus on agriculture, the landscape has not experienced the same pressure from secondary succession and residential development as many other eastern landscapes. The landscape has remained relatively stable since before the Civil War. Barn owls, American Kestrels, and other grassland birds continue to be a part of the Great Valley and this area should be a significant focus for the management of barn owls. Because much of the foraging habitat remains intact, there continues to be good management potential. Lance and Jill Morrow, and more recently Alan Williams, have been working barn owls in a portion of the Great Valley in Virginia and have had surprising success in managing breeding pairs. Their work has demonstrated that successful management is possible in areas where appropriate habitat remains.