Still flying at 90

White ibis population explodes in Virginia

January 17, 2019

Virginia peregrines set record high in 2018

March 30, 2019By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

March 29, 2019

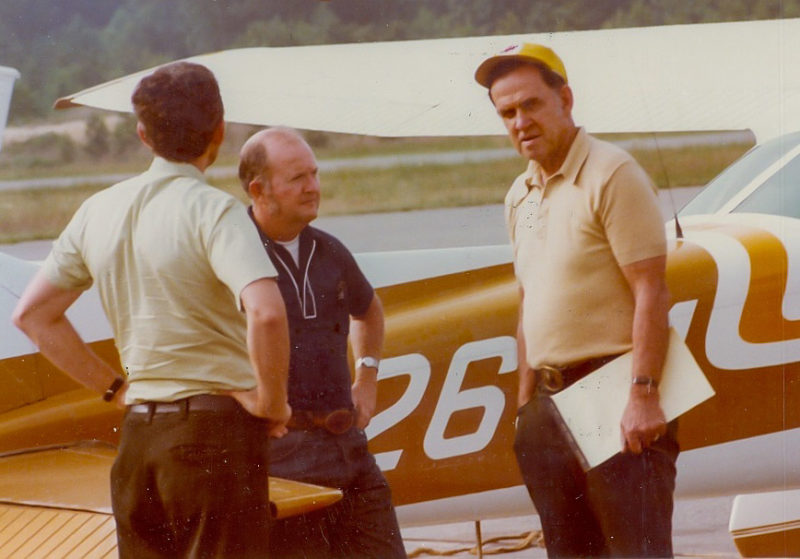

Mitchell Byrd turned 90 in August of 2018, but in early March of 2019 he toed the flight line and was back in the survey plane to begin his 43rd season of eagle work in the lower Chesapeake Bay. Somewhere along the way he has lost the mutton chops that he wore when the survey began, but after more than 25,000 nest checks he still maintains an enthusiasm for eagles and the effort. He, along with Bryan Watts and long-time pilot Captain Fuzzzo, have had a front-row seat to see one of the world’s most iconic species rise from the ashes. It has been quite a ride.

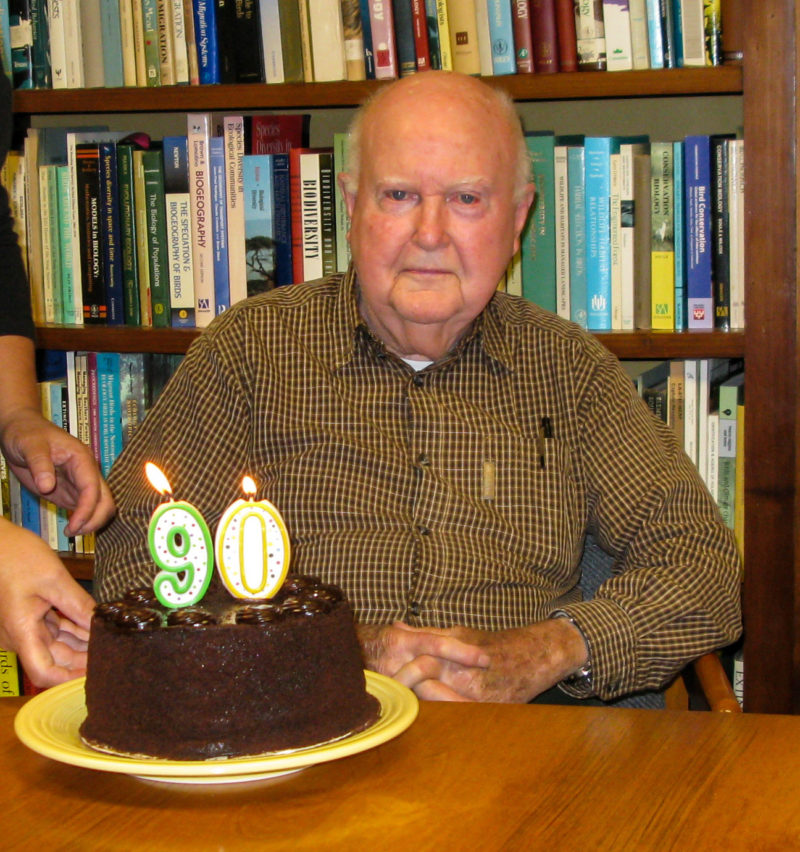

Mitchell Byrd with birthday cake in the CCB conference room in August of 2018. Photo by Bryan Watts.

When Mitchell Byrd took over the annual bald eagle breeding survey in the lower Chesapeake Bay, President Ford had just pardoned Tokyo Rose, Apple Computer had just been incorporated, Gary Gilmore had been executed by firing squad, and Star Wars was about to premier. Mitchell was chairman of the biology department at the College of William & Mary, had a full teaching load, a research lab that was overflowing with graduate students, and was involved with several professional societies. With the recent passage of the Endangered Species Act, it was a heady time for endangered birds. Mitchell was already heavily involved with the recovery of several species. But duty called and Mitchell agreed to take over the survey as part of the long-term conservation partnership with the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries.

As the adventure began with the first anxious flights in March of 1977, it was not possible to know that the survey would become such a long-term commitment or how eagle recovery would unfold in such a spectacular fashion. For the first two years he found no breeding eagles on the entire James River and few on the other major tributaries, making for lonely flights that felt like eerie wakes. But the first pair appeared on the James River in 1979, and the population began to show signs of life during the 1980s. During the 1990s, the population would regain its footing and surpass recovery goals established during the 1970s. During the 2000s, exponential growth had become obvious on the landscape with nests popping up on virtually every point and creek. By the 2010s, breeding densities within some portions of the lower Bay were among the highest ever recorded throughout the range, and the population had clearly shifted from growth to the infighting and negative feedback that ultimately regulates population size. The slow and lonely flights of the 1970s are long gone, and the stack of data sheets used to record observations has grown thicker year after year. The flight has become intense, often with only seconds between nests and days of flying that typically stretch past eight hours. Dr. Byrd retired from William & Mary as Chancellor Professor of Biology in 1993. Now, most of his graduate students have retired. But the work with eagles has continued. There are often no easy explanations for what factors lead to sustaining long-term projects and commitments. What starts out as a desire to answer a set of questions becomes a committed passion to learn more, and to contribute more. Maybe over time the committed passion becomes a sense of place or being or friendship that eclipses even the grand spectacle of eagles. Whatever the spark, Mitchell’s commitment and energy across the decades have been astounding.

Related posts

A brood of osprey in Mobjack Bay showing a well-fed chick (left) and an emaciated chick (right). The chick on the right would die the following week due to starvation. Work in Mobjack Bay over a 40+ year period has shown that both reproductive rates and food delivery rates have declined dramatically. The decline in provisioning has led to an increase in brood reduction or chick loss due to starvation. Photo by Bryan Watts.