White ibis population explodes in Virginia

Have you seen me?

January 15, 2019

Still flying at 90

March 30, 2019 By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

January 17, 2019

Some species creep forward across the landscape. They fortify their troops and slowly take ground with the restraint of a calculated military campaign. Other species jump with wild abandon across the landscape, consuming new ground and seemingly unconcerned about the basic supports that will be needed to sustain their advance. White ibis fall into the latter category. Unconcerned with species norms, white ibis have been documented to pick up entire colonies supporting tens of thousands of pairs and move completely in a single year. What triggers these moves is unclear but they have left unsuspecting graduate students with no date to the prom and thesis projects citing “unanticipated events.”

In the beginning, the white ibis story in Virginia appeared to be a dud. Breeding was confirmed on Fisherman Island during the summer of 1977, but the species sat idle within this toe hold for more than 20 years. We thought that they had been constrained by ecological requirements during early brood rearing that would limit colonization of heronries on the offshore barrier islands. During the 1980s, research in South Carolina had shown that salt glands in young ibis did not develop until three weeks of age, forcing adults to move long distances to mainland sites to gather fresh-water prey until the young were able to tolerate their favorite but salty fiddler crabs. Distance to the mainland might limit the formation of the more isolated colonies and hold the species in the state to curiosity status. But in the early 2000s, small numbers colonized the Cobb and Wreck island heronries in a breakout move that would foretell the future.

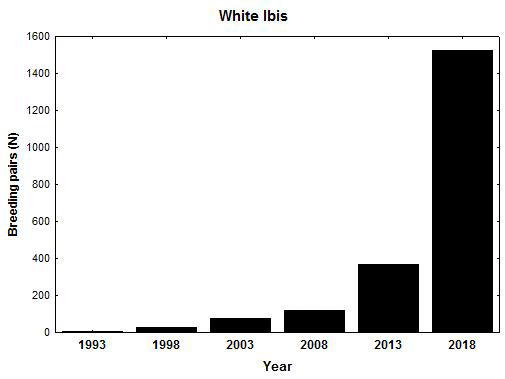

Over the past decade, the white ibis has become the most visible wader in the marshes throughout the Delmarva seaside. For those of us accustomed to seeing the elegant, well-mannered flocks of snowy egrets, little blues and tricolors coming and going from their usual tide pools and ponds, the bold entry of ibis into the area has been a shock to the system. They appear to be everywhere. The most consequential development that appears to have ignited the population has been the colony along the Chincoteague Causeway. Whatever the cause, the Virginia population has exploded, increasing from less than 400 pairs in 2013 to more than 1,500 pairs in 2018. Given the demographics, this explosion could not have been driven by good productivity alone but represents a flow of birds into the state from populations to the south. We should expect further expansion in Virginia and likely states to the north over the next few years.