CCB collaborates on study of winter ecology of Ipswich sparrows

A heron’s tale

October 3, 2018

Clean blood for eaglets within lower Chesapeake Bay

January 14, 2019By Fletcher Smith | fmsmit@wm.edu | (757) 221-1617 & Sydney Bliss (M.Sc candidate at Dalhousie University)

October 3, 2018

Color-marked Ipswich sparrow at Chincoteague Island National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Kevin Holcomb and Teta Kain.

Ipswich sparrows spend their lives on the wild edge where the Atlantic Ocean meets land. The entire population breeds on one small sandy island (the aptly named Sable Island) off the coast of Canada, and in migration and in winter they occupy sandy coastal habitat. These sparrows have evolved in this constantly changing environment, their plumage blending in perfectly with the open sand and tones of mid-winter vegetation. The dunes in which Ipswich spend their winters are susceptible to high-intensity nor’easters that strip seeds from plants and flatten or rearrange entire swaths of habitat. Heavy snow storms on the outer coast can bury most of the available seed crop. Severe cold temperatures on the northern end of their winter range likely cause some degree of facultative migration to warmer climes. But still these birds persist, and the degree to which they have adapted to this harsh environment is nothing short of amazing.

The sun sets on the dunes of Delaware. This outer fringe habitat bears the brunt of massive winter storms. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The dynamic nature of the dune/ocean interface makes for dramatic changes in annual occupancy. For instance, during CCB’s surveys of Metompkin Island in 2012 and 2016 we found over 20 birds/km of beach. To put that density into perspective, the seminal winter survey work conducted by Stobo and McLaren in 1971 found peak densities in the mid-Atlantic of 3 birds/km. This winter, with the dune habitat remaining unchanged to the human eye on Metompkin Island, we only recorded 1 bird/km. The annual variation in habitat used is likely summed up in one word: food. The birds likely have site fidelity between years if the seed base doesn’t change much, but our counts on Metompkin Island this past winter likely reflect a crash in dune grass seed production since our 2016 survey. The focus of our surveys during the winter of 2017-2018 was to determine the density and distribution of the sparrows across the mid-Atlantic from Delaware to North Carolina. We surveyed approximately 237 total kilometers of dune habitat throughout the field season from January through mid-March. We found a range of densities of the sparrows across the landscape, with the highest densities unsurprisingly recorded in wild natural dunes. We plan on expanding these surveys during the upcoming winter to better understand the distribution of sparrows across the winter range.

To better understand the processes that affect Ipswich Sparrow population size, researchers have begun a long-term study of the population using mark-resight techniques. To mark the sparrows, birds are affixed with unique combinations of colored leg bands. To date, 639 sparrows have been banded on Sable Island, Canada breeding grounds and on Delmarva Peninsula, USA wintering grounds. Sparrows will continue to be banded at these locations over the next several years and resighting surveys (i.e. finding the birds after banding) will occur in multiple locations along the eastern seaboard. The history and location of birds that are resighted can be used to make inferences about the demography of the marked population. For instance, researchers will be able to determine which life cycle stages (breeding, migration, or overwintering) incur the highest mortality in the population, estimate population size, and understand how various ecological factors affect population size.

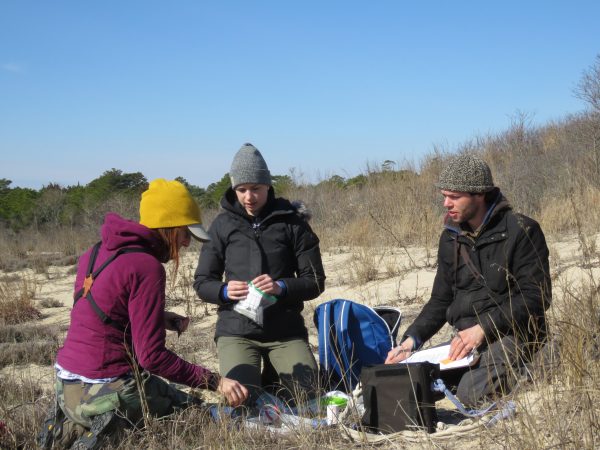

Laura Duval, Sydney Bliss, and Lucas Berrigan process captured sparrows. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The difficulties associated with following individual animals have long been a barrier to studying migrations. With the recent miniaturization of radio-transmitters, plus an extensive array of telemetry receivers in eastern North America (Motus Wildlife Tracking System), it is now possible to track small songbirds from start-to-finish during migrations. To better understand Ipswich sparrow migration, we affixed sparrows with radio transmitters on the Delmarva Peninsula in winter 2018. These small transmitters weigh 0.7 g and are attached to sparrows using a backpack-style harness. Using the Motus array, these sparrows were tracked thousands of kilometers from the Delmarva Peninsula to Sable Island during spring migration. Data from these transmitters will help us understand the migration of these birds, including what routes they take to Sable Island, where and for how long they stop to rest along the way, how long the journey takes, and constitutes the most dangerous legs of migration. Further, researchers can identify key areas that support migrating sparrows for management and conservation.

Image of a radio transmitter attached to bird. Photo by Chance Hines.

Color-marked Ipswich sparrow hides in the dune grasses. Photo by Laura Duval.

The field crew celebrates the last transmitter deployment of the season at Cape Henlopen State Park (from left to right: Lucas Berrigan, Sydney Bliss, Chance Hines, Laura Duval, and Fletcher Smith). Photo by Chance Hines.

The 2017-2018 winter work was conducted with the help of many partners, land managers, and funding agencies, including the National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Dalhousie University, Acadia University, Delaware State Parks (Cape Henlopen, Delaware Seashore, and Fenwick Island), Delaware Department of Natural Resources Division of Fish & Wildlife, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, The Nature Conservancy, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, the North Carolina National Estuarine Research Reserve, and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. Ned Brinkley, Zak Poulton, and Courtney Check all contributed significant volunteer time and effort in support of this study.