A heron’s tale

Female peregrines under pressure

October 2, 2018

CCB collaborates on study of winter ecology of Ipswich sparrows

October 3, 2018By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

October 3, 2018

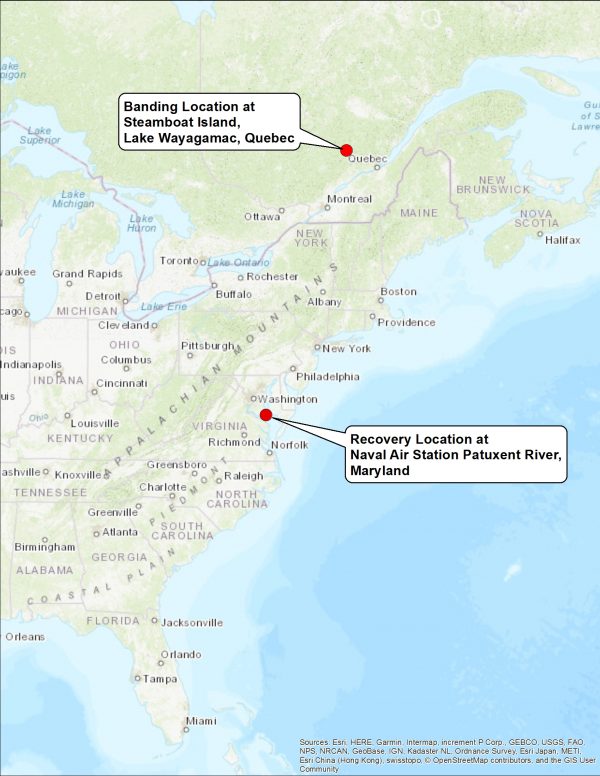

On 1 May, 2018 while banding on the Patuxent Naval Air Station in Maryland, we found a great blue heron tarsal bone in one of the eagle nests. The bone was clean but fresh and had an aluminum band. After sending the band number to the Bird Banding Lab, we were informed that the heron had been banded on 5 July, 2001 as a nestling in Quebec, Canada, making it in its 18th year when it was killed. Upon further correspondence with the Canadian Wildlife Service, it was determined that the bird was hatched in a colony on Steamboat Island in Wayagamack Lake by Louise Champoux. The bird was included in a study monitoring contaminant exposure of great blue herons throughout the region around the St. Lawrence River. This chance encounter helps to shed additional light on two lingering questions about great blue herons within the Chesapeake Bay including 1) what is the migratory status of great blue herons using the Chesapeake Bay and 2) what is the interaction between great blue herons and eagles?

Eagle nest on the Patuxent Naval Air Station where great blue heron tarsus was recovered. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Due to the latitudinal position of the Chesapeake Bay, the migratory status of many bird species is transitional such that populations north of the Chesapeake Bay are migratory and those south of the Bay are non-migratory. To make things even more confusing, some of the species that we have assumed to be year-round residents because we see them here in the Bay all year actually go through a “changing of the guard” where our breeding birds migrate out for the winter only to be replaced by birds from northern breeding grounds. Other species show a mixed strategy. For example, through tracking our peregrines with satellite transmitters, we have determined that some of our birds migrate south and some remain resident through the year. Although we know that great blue herons near the northern limit of their breeding range migrate south to open water for the winter, we have not known if or how these populations might use the Chesapeake Bay. It appears from this recovery that at least some of these birds winter here in the Bay. We know very little about the possible movement of Chesapeake Bay breeding birds out of the Bay to spend the winter.

Tarsus of great blue heron from eagle nest with tarsal band. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Map of the colony location on Wayagamack Lake where the bird was hatched and banded in 2001 and the location where it was recovered in 2018. Data from CCB.

The remarkable recovery of bald eagles within the Chesapeake Bay has had a clear downside for species that are included in eagle diets. Increasingly, some of these prey species are other waterbirds such as ducks, gulls, cormorants, and some herons. Over the past 20 years, we have suspected that the colonization of great blue heron breeding colonies has led to the splintering and movement of colonies, possibly due to predation on heron nestlings. Adult great blue herons are large birds to take, even for bald eagles. Despite their size, we have received periodic observations, photos, and videos from the public showing eagles hunting great blue herons. Some of these hunts have been successful. Finding this bird in the nest is further evidence that great blue herons are included in eagle diets during the breeding season.

Related Stories