Networking Eagles

Flying to Mecca

March 30, 2018

A good year for woodpeckers

April 3, 2018An adult eagle hunting within the upper Chesapeake Bay with a transmitter deployed by CCB. Movement information from 56 tracked eagles was used in a study to examine the structure of eagle roost networks. The first of its kind, the study provides important insight into the protection and management of eagle roosts.

By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

April 2, 2018

Nonbreeding bald eagles are highly social and form communal roosts around profitable foraging sites. We have known for decades that eagles frequently switch back and forth between different communal roosts but have lacked the movement information to evaluate the basic structure of roost networks. The relatively recent development of GPS transmitters and other tracking devices that have enabled the remote tracking of large samples of eagles has opened a new era of data collection with the potential to view individual roosts within a network context. Bryan Watts from CCB and Rodney Dyer from the Center of Environmental Studies at VCU have used movement data from 56 eagles outfitted with satellite transmitters to evaluate the roost network within the upper Chesapeake Bay. The study entitled “Structure and resilience of bald eagle roost networks” was recently published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

An adult eagle hunting within the upper Chesapeake Bay with a transmitter deployed by CCB. Movement information from 56 tracked eagles was used in a study to examine the structure of eagle roost networks. The first of its kind, the study provides important insight into the protection and management of eagle roosts. Photo by Robert Lin.

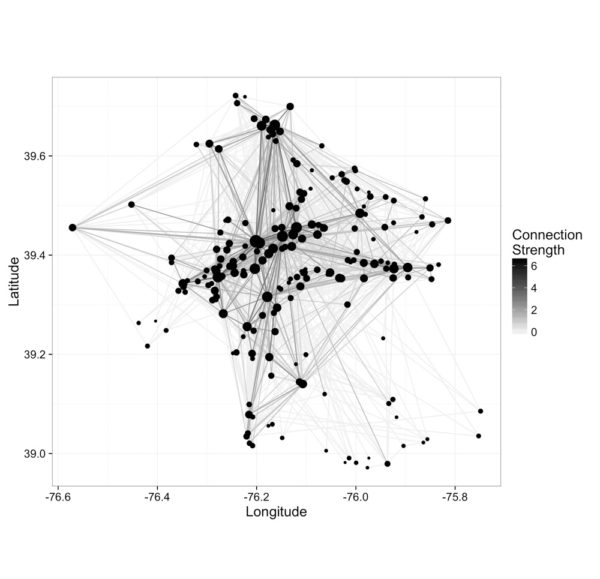

The researchers used 14,464 midnight locations to determine the use of communal roosts and 2,634 movements between roosts on successive nights to evaluate the pattern of connectivity between roosts. Among other findings, the study revealed that the structure of the 212-roost network was consistent with the well-known scale-free network. The scale-free network is a common form where the majority of nodes (roosts in this case) have few connections to others and very few nodes (referred to as hubs) have many connections. Hub roosts serve as bridges between large numbers of other roosts, have the shortest travel times to other roosts and the greatest overall influence on network functioning. More than 50% of roosts were connected to fewer than 10% of other roosts and only seven had connections to more than 50% of the roost network. Incredibly, the Sod Run roost on Aberdeen Proving Ground was connected to 204 (96.7%) of the possible 211 other roosts. This roost was Grand Central Station and the central hub of the entire network.

Diagram of the bald eagle roost network within the upper Chesapeake Bay illustrating the interconnections between roosts. Circles indicate roosts where size is proportional to connectivity and associated with the contribution to function of the overall network. The darkness of lines indicate the strength of connections between roosts. Data from CCB.

Bald eagle communal roosts are protected by federal law. Understanding the structure of roost networks helps us to make better decisions about roost protection and management. One feature of the study was to evaluate the effect of losing individual roosts on the functioning of the overall network. Not surprisingly, the effect of roost removal on overall network function was directly proportional to the connectivity of the roost being removed. Removal of the majority (>90%) of individual roosts would have relatively little impact on the network. The study identified 18 highly connected roosts that are important to network function and that should be the focus of any management strategy.

Whitewash and shed feathers are the telltale sign of a communal roost. This photo was taken under the Sod Run roost within Aberdeen Proving Ground that was shown to be the Grand Central Station of the upper Chesapeake Bay roost network. Photo by Libby Mojica.

Nestling eagle fitted with satellite transmitter. A cross-section of eagle age classes was tracked and included in the network study. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Results from the network study provide insight into the basic ecological question of why eagles gather together. One of the proposed advantages of sociality in nonbreeding eagles is food finding through following behavior from communal roosts. Some eagles have been shown to gain an advantage from associating with roosts by increasing their likelihood of finding or stealing food. This benefit is believed to be particularly great for young, inexperienced eagles that have yet to master hunting skills and often resort to stealing or scavenging to meet their energy needs. Hub roosts may represent concentrated information resources that may be visited periodically by eagles from throughout the network to stay in the information loop.

Related posts

Two whimbrels, including an adult (foreground) that exhibits worn body plumage, especially along the scapular region, and a juvenile (background) with fresher plumage. CCB collaborated with eBird and used photographs like these to better understand differences in migration patterns between adults and juveniles at migratory stopover sites in the eastern United States. Photo credit: Macaulay Library (ML116488021)