Flying to Mecca

Gender Divide in Bald Eagles

January 8, 2018

Networking Eagles

April 2, 2018By Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

March 30, 2018

Fletcher Smith and I had been working birds on the Acadian Peninsula for ten days. We had been flying surveys of blueberry fields and heath barrens, driving survey transects, observing the work of the berry wardens, and watching the birds coming into fields at dawn to get a sense of how foraging flocks worked the landscape. We were spending evenings following birds out of fields to locate communal roosts. Most of the birds on Miscou Island and the northern portion of the peninsula were concentrated in Petit-Shippagan, a simple crossroads with a dozen houses, many of which have private blueberry fields in back. More than 300 birds had been feeding in one field for the past four days to the chagrin of the farmer who made hourly drives around the field firing a shotgun to protect his only cash crop from the birds. The birds had come from western breeding areas to their late summer staging grounds in the Canadian Maritimes. They would spend three gluttonous weeks here eating, resting, and putting on fat – their last tastes of summer before moving on for the winter.

Whimbrels with tremendous fat reserves from feeding on blueberries take off from the Acadian Peninsula headed out over the Atlantic. Next stop, Amazon Delta. They will need this fat to fuel the 6,000-km nonstop flight. Photo by Bryan Watts. Photo by Bryan Watts.

We sat in stake-out position along the southern corner of the field watching for birds to fly out for the evening to roost. The birds were unusually skittish, rising and resettling every few minutes. Finally, 32 birds rose with purpose and flew southeast, a sector with no known roosts. I started the car and hurried after them hoping to maintain contact and get a bearing that we could follow up on in the coming days. To my surprise, the birds were following the two-lane road to the small town of Lameque and I drove directly under the flock making just under 48 kph for11 kilometers. As the flock flew over the Lameque fire department, I turned off, parked, and ran out to the end of the commercial dock to set up a scope and watch the birds emerge out over the water. They were flying toward a treeless island in the back corner of the bay and I was excited that they were about to reveal their secret roost. But the birds overflew the island, and as they gained air over the far tree line I realized that they were not going to roost. They were leaving.

I walked back to the car realizing that it was too late to get back to the berry field to pick up another flock and sat in the parking lot to watch the sun lay down on the water toward the Gaspe Peninsula. I had unknowingly given the flock a send off from Berryville. They were heading out over the open Atlantic into the unknown. It would be impossible for the flock to know what storms might be brewing in Hurricane Alley. They would fly nonstop for six days and cover more than 6,000 kilometers. You have to respect any animal with the bravado to fly out over the open ocean with no safety net. I knew that the next ground they would touch would be in Brazil and the next meal they would eat would not be blueberries, but tropical fiddler crabs. Bem-vindo ao Brasil! They were going to the land of plenty.

The birds were completing their annual pilgrimage to the shorebird Mecca of the Western Hemisphere, the Amazon Delta. They will spend more than seven months here in the most critical wintering grounds to the population in the Western Hemisphere.

Whimbrel with one of the early 9.5-g transmitters used to track birds throughout the year. The tracking project has revealed a tremendous amount of information about the ecology of this wide-ranging population. Photo by Bart Paxton.

The gravitational pull of the delta reaches throughout the entire hemisphere, gathering birds of many stripes. They come from all corners. To date, we have tracked 26 whimbrels from the Mackenzie River and Hudson Bay Lowland breeding areas to their winter range and >90% have wintered within the Amazon Delta. Some of these birds fly directly to the delta while others make landfall in Venezuela. Early in the tracking project we thought that the latter birds would overwinter in these locations, but during the late fall they would slowly skip east along the shoreline to join the others in Mecca and pay their respects to the delta.

We all know of the vast Amazon rainforest (lungs of the word; greatest assemblage of species on the planet) and the Amazon River (largest drainage basin in the world; holds more than one-fifth of the world’s fresh water). Much less is known about the critical importance of the Amazon Delta. In addition to carrying a tremendous supply of fresh water, the river produces the largest sediment discharge of any river. The enormous plume of sediment and nutrients that is spewed from the mouth of the river is pushed hundreds of kilometers out into the Atlantic. The plume collides with the North Brazilian Current and is directed west, fertilizing more than 1,500 kilometers of the South American coastline. The nutrients spread over this vast area create a productivity bonanza. It is this natural gusher of productivity that attracts the whimbrels each winter along with throngs of other waterbirds.

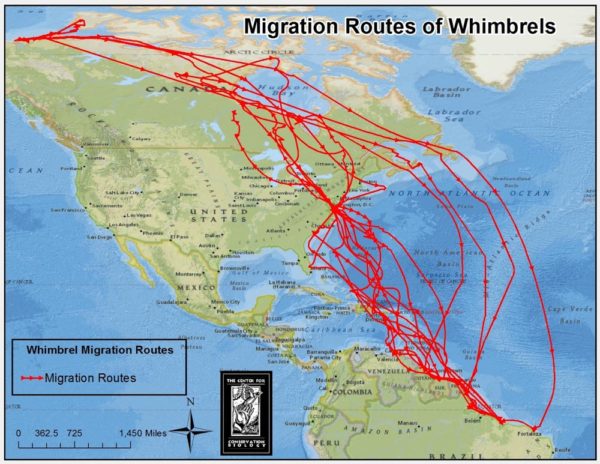

All roads lead to the Amazon. Whimbrels have taken a number of fall migration routes but almost all ultimately have led to the Amazon Delta. Birds leaving the Canadian Maritimes have typically taken a long transoceanic route. Data from CCB.

The power of the Amazon is drawn from its wildness – the unfettered flow of water, the forested drainage basin, the sheer power to wield its way on the entire coast. Plans for infrastructure transformation within the Amazon basin threaten this wildness, including a cross-national highway system, river and sea-ports, a sequence of dams for transportation river-ways, and hydro-electric plants. Will we see this great river be made impotent by dams like the whimpering Mississippi or be smothered by agriculture and contaminants like the Mekong? Will we consider this frontier something to be conquered and exploited or something to be preserved and protected? The river is still wild and its future is in our hands. We should all ask ourselves if we have learned anything from how we have treated many of the world’s iconic rivers. Do their fisheries still thrive and do they still serve the many consumers that once depended on them?

Watching the flock leaving the Acadian Peninsula, it is hard not to be concerned about the perils they may face out over the open Atlantic. Perils like storms and winds that we have no control over and that have shaped the evolution of their migration pathways. Harder still is wondering what they will find when they arrive after their long flights in the coming decades. We can hope that they will still find their land of plenty.