Studying the Red Knot in Coastal Georgia

Ipswiches cope after Jonas

April 4, 2016Another Crowned Eagle Lost to Electrocution

April 4, 2016

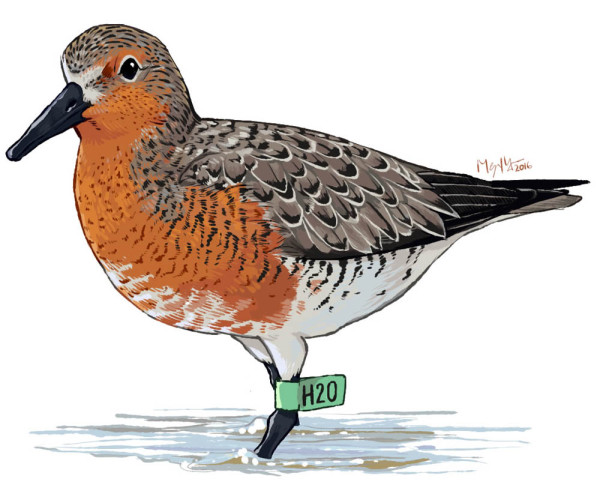

Illustration of a tagged red knot. Drawn by Megan Massa.

The day will begin around six hours before high tide. Researchers will prepare enough food and water for the day ahead, and double check that all field gear is loaded up. The boat will drop into the water approximately four hours before high tide, and we will arrive on the island about three hours before high tide. The sand bars still expand for what seems like miles in every direction. This is the result of the up to nine-foot tides that characterize coastal Georgia. But as the water creeps up and the bars become smaller, the birds we are studying become more concentrated and much easier to access. By the time the tide reaches its apex, the birds will be in astonishingly huge concentrations, with upwards of 10,000 shorebirds (mixed flocks) occupying sand bars as small as one or two acres in size. But we are here to work with red knots, not the other shorebirds, and will focus our efforts on them during the mid-rising to mid-falling tide periods.

A mixed shorebird flock (red knots, dunlin, and sanderlings) foraging at high tide. Photo by Hillary Thompson.

The red knot is a robin-sized shorebird (and formerly called “beach robins”) that has two contrasting wintering strategies. A portion of the population will migrate to southern Argentina and Chile from breeding grounds in the high Arctic, while another portion will winter as far north as Virginia, all through the Caribbean and northern South America. When we arrive in Georgia in early April, the wintering population will be present, but the long distance migrants will not arrive until early May. We know all of this because a large percentage (around 5%) of red knots are individually marked with coded leg flags. These knots were captured in a variety of locations, from Delaware Bay to coastal Massachusetts (green flags), the breeding grounds in Canada and coastal stopover locations there (white flags), southern Chile (red flags), coastal Argentina (orange flags), and Brazil (blue flags). The majority of flags seen in April will be green (banded in the USA) but as the season progresses more of the long-distance migrants will arrive, displaying the full range of flags representing the above locations. This marked population makes studying arrival times, stopover duration, and population estimation easier than working with an unmarked population.

Red knot tagged in Argentina. Photo by Perri Rothemich.

This upcoming field season, our goals are to project a population estimate utilizing the coast of Georgia, map the important stopover locations, and attempt to increase the public awareness of red knots using the South Atlantic Coast of the US. During the 2015 field season, we saw peak numbers of red knots in the 7,000-8,000 range, and hopefully we will be neck-deep in knots again this year.

2015 technician Amy Whitear resighting marked red knots near Tybee Island, Georgia. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

This project is a collaboration between the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Non-game Division, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey, Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, and The Center for Conservation Biology. Numerous other entities have assisted us in this multi-year project, including staff from Little St. Simons Island, St. Catherines Island, the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Georgia Riverkeepers staff, and staff from Cumberland Island National Seashore. We will be relying on volunteer help from some of the best “resighters” out there, especially Pat and Doris Leary.

This red knot resighting project is receiving funding from Gulf Power and Southern Company through their National Fish and Wildlife Foundation partnership.

Written by Fletcher Smith | fmsmit@wm.edu | (757) 221-1617

April 4, 2016

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts