Wild bet on woodpeckers pays off

Untangling dispersal in coastal peregrines

March 29, 2016At Home on the Islands

March 30, 2016

Adult male red-cockaded woodpecker showing the seldom seen patch of red feathers. Photo by Bryan Watts.

It was 5 April, 2000 and we (Bryan Watts, Dana Bradshaw and Marian Watts) caught the 5:40 AM ferry across the James River and made the 30-minute drive south to take up strategic positions in the woods before 6:45 AM. Just after dawn, woodpeckers began to emerge from their roost cavities calling and rallying together in the center of the cluster of trees. We would count four on this morning, and over the next week an additional nine birds. Thirteen plus two bachelor males within other sites were all that remained of their kind in Virginia. Once relatively common and distributed throughout the southeastern part of the state, the red-cockaded woodpecker suffered dramatic losses with the exploitation of pines during the colonial expansion and much deeper declines with the movement toward the production of wood products through short-rotation pine plantations. However, as recently as 1975, 60 different breeding sites were still known. By 2000 nearly all of those sites had been milled and the population was perched on the edge of the abyss (read about the decline).

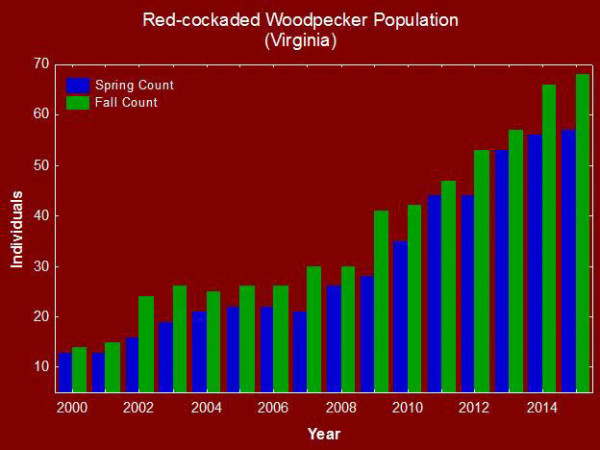

Graph showing the number of red-cockaded woodpeckers resident within the Piney Grove Preserve in Sussex County, Virginia during spring and fall census periods (2000 – 2015). Data from CCB.

The 1998 purchase of the Piney Grove Preserve, a 2,000+ acre stand of old pines, by The Nature Conservancy represented the final bet by an exasperated conservation community to save the species in Virginia. The site was the last game in town and its purchase was made with a clear understanding of the long odds for success. A coalition of the willing that included The Nature Conservancy, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and The Center for Conservation Biology formed with an initial objective of growing the population within the preserve. The plan was to build a nucleus for recovery.

Roost cavity for red-cockaded woodpecker within the Piney Grove Preserve. The photo illustrates resin wells maintained by the woodpeckers to promote a protective sap flow around the nest cavity. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Despite the long odds, with the hard work of many, many individuals, the bet with Piney Grove Preserve has paid off. During the winter of 2015-2016, CCB counted 68 woodpeckers within the preserve, an incredible five-fold return. In just 15 years the conservation experiment has reversed a 400-year-old decline. Although the acres of this initial purchase are now approaching their capacity for woodpeckers, other initiatives are pushing forward. The purchase of several thousand acres of pineland (The Big Woods) adjacent to the preserve by the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries represents great promise for the future of pineland birds in the state. The translocation of eight woodpeckers into the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in October represents a second phase of recovery. The Piney Grove Preserve has truly fulfilled its intended role as a nucleus for recovery.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

March 29, 2016

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts