Untangling dispersal in coastal peregrines

Grace Retraces Flight Back to TRS Mar 26, 2016

March 28, 2016Wild bet on woodpeckers pays off

March 29, 2016

Natal dispersal is the movement of an animal from the place of birth to the location where it will ultimately breed. For the majority of bird species, dispersal progresses through three phases including 1) a decision to leave the natal territory, 2) a transition that includes exploration or prospecting and 3) a decision about where to settle or establish their own breeding territory. Of these three phases we know the most about when young birds leave their natal territories. We know far less about prospecting and, for many species, even less about where young birds ultimately settle. Famously, peregrine falcons have an extended and dramatic period of exploration (read about the wanderings of young peregrines from Virginia as revealed through satellite tracking conducted by CCB). They are named for their wide peregrinations. In stark contrast to these extensive wanderings when it comes to establishing breeding territories they actually settle relatively close to their natal sites.

Adult female falcon that is currently nesting on a bridge near West Point, Virginia. This female was originally banded 86 km away as a nestling on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Photo by Bryan Watts.

For more than two decades, a large portion of the peregrine falcons produced in eastern North America have been marked with two bands including a United States Geological Survey (USGS) aluminum band with a numeric code and a field-readable band with unique combinations of letters and numbers. In most instances reading the USGS band requires that the bird be captured. However, the field-readable band may be read using spotting scopes, binoculars, or cameras. The use of these bands has allowed the community of biologists (and the public) to resight these birds over time and to contribute a great deal to what we know about their spatial ecology and natural history.

Adult female peregrine falcon emerges from a nest box to be caught by a camera trap. Most of the resights of breeding adults in Virginia have been made with camera traps.

Since the early 2000s when Shawn Padgett pioneered the use of video cameras on nests to read bands, CCB and other groups have used camera traps to identify breeding adults. This activity has opened up the possibility of addressing a long list of questions, including how long peregrines live (read about James the longest living wild peregrine known), the degree of relatedness within the breeding population (we have documented close inbreeding between siblings and parent-offspring pairings), lifetime reproductive success, and patterns of dispersal, among others.

Adult female falcon stands on a nest tower on the Eastern Shore and is caught by a camera trap.

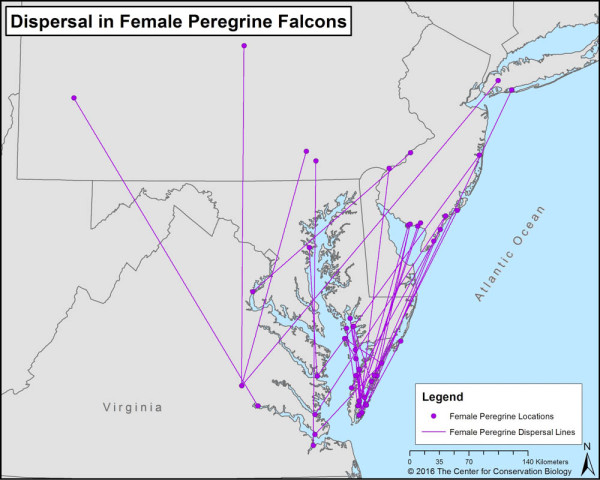

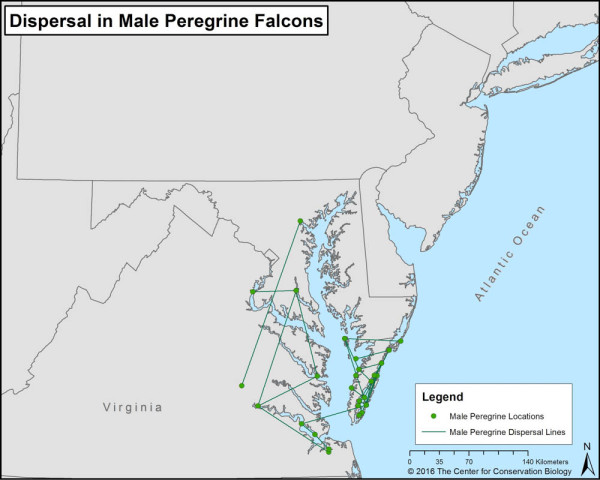

Like many other raptor species, dispersal serves to reduce the likelihood of pairings between parents and offspring. In addition, differences in dispersal distances between males and females makes pairings between full siblings less likely. Dispersal distances documented by CCB and partners within coastal Virginia range from 4 to 207 km for males (median of 24 km) and 0 to 473 km for females (median of 105 km). The banding and resighting efforts in Virginia are building an integrated database that is beginning to untangle several aspects of peregrine ecology that have been notoriously difficult to address.

Dispersal events by female peregrine falcons either banded or nesting in Virginia. Data from CCB.

Dispersal events by male peregrine falcons wither banded or nesting in Virginia. Data from CCB.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

March 28, 2016