Tracking and Training on Chiloe Island, Chile

Bald Eagle “HE” Feb/17/2009 – Jan/6/2016

January 11, 2016

Grace Returns to North Carolina Jan 17 2016

January 18, 2016

Recycled bottle cap mosaic of Hudsonian godwits. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Several species of shorebirds make truly epic journeys, flying non-stop from Alaska to New Zealand (6,835 mi) or from Atlantic Canada to Brazil (4,350 mi). These journeys are fueled by stores of fat built up during migration stopovers or on wintering staging areas. One of the most powerful migrants in the Western Hemisphere is the Hudsonian godwit. The godwits are comprised of three disjunct breeding populations, one in Alaska, one in the Mackenzie Delta, and one in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. These high-latitude nesting birds make epic non-stop flights from the breeding grounds to stopovers in the Amazon and Orinoco river basins, then continue on to wintering locations in Argentina and Chile.

Hudsonian godwits roosting at high tide. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

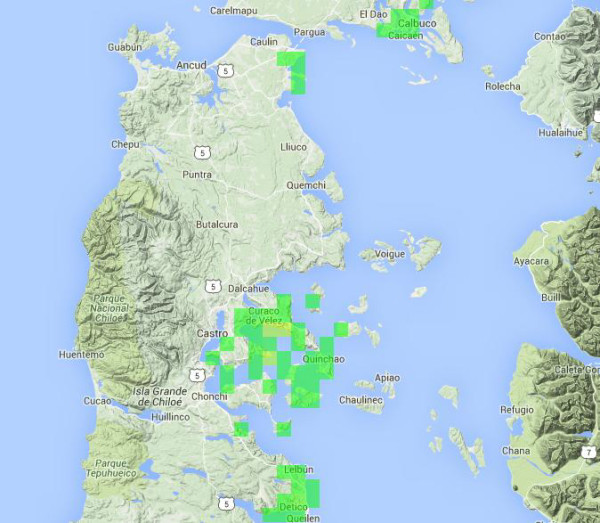

The world of shorebird biologists is very small. There are probably only hundreds of biologists that study these fascinating creatures in the entire Western Hemisphere. I had the good fortune of talking to a Chilean colleague about satellite tracking of shorebirds at a professional meeting, and that discussion led to a trip to the island of Chiloe, located in the southern Pacific Coast of Chile. The primary goal of the trip was to assist local biologists in tagging of Hudsonian godwits with satellite transmitters and to train them to potentially tag other shorebirds in the future. In total, five godwits were tagged during the trip, all within the Quinchao Island on a high tide roost near Chullec. The primary goals of this project are to determine winter territory size of godwits and to determine the various sites that are used for foraging and roosting. This information will be used to protect any unknown high-use sites for the godwits.

[easy_image_gallery]

The results of the tagging are filtering in, and some surprising movements are being recorded. Shorebirds tend to have high site fidelity to feeding and roosting sites in winter, but their movements in-between tides are not well documented. The rugged and remote Chiloe coastline makes fieldwork particularly difficult. At least two of the godwits appear to be making large flights to feeding sites 40-50 miles away, or are moving during the winter to better foraging sites. More data is needed to decipher their winter flight patterns, but all five transmitters are sending data on movements and roost sites and we should know more in another couple months.

Composite map of locations of all five satellite tagged Hudsonian godwits so far. Data from CCB.

Trapping team observes a large flock of godwits near Curaco de Veléz. Photo by Claudio Delgado.

Godwit trapping team, including Luis Espinoza, Claudio Delgado, Fletcher Smith, and Jaime Cárdenas. Photo by Claudio Delgado.

The tracking of Hudsonian godwits is a collaborative effort between ConservaciÓn Marina and The Center for Conservation Biology. The success of the trapping efforts was due to the intense scouting and long-term shorebird counts that Luis Espinoza and Claudio Delgado performed prior to my arrival.

Written by Fletcher Smith | fmsmit@wm.edu | (757) 221-1617

January 12, 2016