Tracking a shorebird to the ends of the earth

Grace Arrives at Plymouth, NC Catfish Farm 12/16/2014

December 17, 2014

Grace at the Catfish Farm Dec 16 &17, 2014

December 18, 2014

The journey begins in darkness in Virginia with an early morning flight departing from the Norfolk International Airport in late May. The air is humid, and the days have been hot along the mid-Atlantic Coast. The first leg of the trip is to Toronto, Canada. Subsequent flights take me through the Prairie Provinces (with an overnight stay), and finally on to Yellowknife, Canada. Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories, is where much of the logistical planning for the field season ahead takes place. The main focus of this collaboration between the Canadian Wildlife Service and The Center for Conservation Biology is the satellite tracking of whimbrels throughout their life cycle. The important task of rigging the satellite transmitters for deployment in the field takes place here in Yellowknife. The transmitters are placed in the carry-on luggage as they are irreplaceable if lost. The trip to Yellowknife has taken two days and nearly 3,000 miles are behind me at this point.

A satellite tagged whimbrel shortly after capture. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

After a few days of last minute preparations, the team of biologists, technicians, and student interns leaves via airplane for the small town of Inuvik, located along a main branch of the Mackenzie River. This leg of the journey adds another 650 miles to the total, which is now at 3,650 miles and 4 days of travel time. Inuvik is where the final logistical steps take place; securing helicopter and Twin Otter flights into the bush, purchasing most of the food we will eat for the next 6 weeks, loading up gear at the airplane hangar, filling up gasoline and propane containers, and packing other crucial supplies that will be used in the coming field season. The total weight of the gear approaches 2 tons, and some of it is redundant, but there will be no option to stop at the local convenience store to pick up necessary supplies after we are dropped in camp.

The next leg of the journey begins on the first good weather day (which can be few and far between this time of year), and the team splits into two groups, one going with the helicopter and one with the plane. The helicopter flight from Inuvik to the outer Mackenzie Delta is an eye opener. During this flight, the team will cross hundreds of miles of frozen rivers, lakes, and snow-covered ground. With daily average low temperatures at around minus 20 Fahrenheit between mid-November and early April, ice breakup in the delta can take a while. This intensely long, cold, dark winter is one reason that few people inhabit the northern Arctic region. The spring and summer are best characterized by light. The sun never sets during the field season, and the ice and snow quickly thaw in the midnight sun. The average temperatures during the field season are between 40 and 60 Fahrenheit, relatively balmy compared to the deep cold of winter.

One team helps to unload the plane at a remote landing strip appropriately named Camp Farewell. The other team flies via helicopter to the gravel pad that will be home for the next 6 weeks. The process takes a full day, with the helicopter bringing in loads of gear hanging from a sling from Farewell to the field campsite. After the gear is dropped, the team puts together the equipment that will be used throughout the field season to collect data on nesting shorebirds. All supplies are distributed, including GPS units, pens, pencils, field notebooks, cameras, and banding equipment. The main kitchen area is set up in an igloo-like structure that allows respite from the biting insects. The storage tent is erected and all the food (calculated to be 5 pounds of food for each person each day!) is placed inside. The sleeping tents are placed on the far end of the pad, and a bear fence is erected around them. The possibility of having a bear come into camp to investigate the food tent or gasoline cans is very real, so those items are kept as far away from our sleeping tents as possible. We have put another 120 miles behind us, and can go no further north without swimming in the Beaufort Sea. The journey has taken about a week so far, and nearly 4,000 total miles are behind me.

Frozen tundra in early June 2012 on the Mackenzie Delta. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Helicopter flight in to the Mackenzie Delta shorebird camp in early June 2014. The ice has thawed and left the marshes flooded. You can see the outlines of the Low-centered Polygon habitat (the tops of the vegetation on the ridges are not underwater in this video). Those ridges are the preferred habitat for many nesting shorebird species in the delta. Video by Fletcher Smith.

A view of our base camp in early June 2013. Our igloo like structure is visible just above the flooding waters in the center of the picture. The antennae in the foreground is a decommissioned communication tower that has been home to nesting Rough-legged Hawks, Ravens, and Gyrfalcons in different years. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

A helicopter deposits gear at our base camp using a sling. Our base camp is located on Fish Island, just outside the Kendall Island Bird Sanctuary in the outer Mackenzie Delta, NWT, Canada. Video by Fletcher Smith.

During the flood event of 2013, we had a nearby neighbor (arctic fox) that waited for the waters to recede on an adjacent gravel pad. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

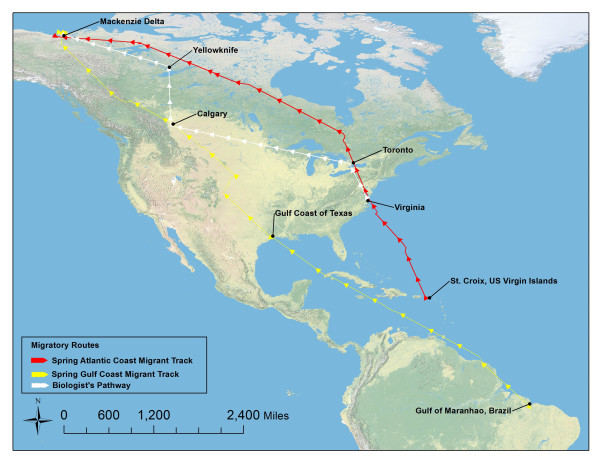

The whimbrel’s migration to breeding grounds started just before my departure from Norfolk on that late May morning. The birds originated from wintering grounds in Brazil, where they spent 7 months in the Gulf of Maranhão region. There they fattened up for the journey north. Whimbrels complete the almost 4,000 mile journey to North American staging grounds in about 5 days. They arrive exhausted, and must build up fat immediately. The two stopover sites for the Mackenzie Delta breeding population are quite different. Along the Atlantic Coast, the vast coastal marshes of Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia host the greater part of the Atlantic migrant population, where they feast on the seemingly endless supply of fiddler crabs. The Gulf Coast migrants stage between Mexico and Louisiana, using habitat ranging from crawfish farms and rice impoundments to natural coastal marshes for foraging and roosting. The Gulf Coast birds have a more varied palate, with fiddler crabs, crawfish, and marine invertebrates making up the majority of the diet at this stopover site. The birds will stay at these sites for close to a month, building up fat reserves and preparing for the next leg of their journey.

Migration begins when the pangs of Zugenruhe become too much to suppress. The birds leave the Atlantic Coast staging areas during a relatively short window; more than 90% of the birds leave within a 5 day period in the latter part of May. Many thousands are observed annually during this time in coastal Virginia. During the 2014 season, a new record of 8,192 individual whimbrels was counted, and nearly 6,000 of that total were observed between the 24th through 26th of May alone. The birds fly from the Atlantic Coast to the breeding grounds, covering the 4,000 miles to the Mackenzie Delta in a 5 day non-stop flight, quicker than it takes a biologist to cover the same distance (although biologists stop along the way to eat, sleep, and drink). The Gulf Coast whimbrels utilize a different migration strategy. They depart the Gulf Coast habitats in early May, stopping for short periods along the Platte River in Nebraska and in the irrigated farmlands of southern Alberta and Saskatchewan. The final 1,500 mile flights to the breeding grounds take place in the third week of May.

Map detailed routes taken to the Mackenzie Delta. Shown are tracks from two migrating whimbrels (a Gulf Coast and an Atlantic Coast migrant) and the track the biologist took getting there. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Satellite tagged whimbrel. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Once the whimbrels (and other shorebirds) and biologists converge on the same marsh-dominated breeding grounds of the outer Mackenzie River Delta, the real work begins. As part of the Arctic Shorebird Demographic Network (ASDN) and the Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM) programs, the Mackenzie Delta camp monitors the breeding success, population densities, annual survival, and other important parameters that are necessary in answering questions regarding population declines of shorebirds breeding in the Arctic regions.

Boating on the Beaufort Sea in the outer Mackenzie Delta, Canada. The use of boats was necessary to move between the primary field site (Fish and Taglu Islands) and secondary field sites (Niglintgak Island and outer islands of the delta). Video taken by Tyler Kidd/Canadian Wildlife Service.

After locating a nest, a walk-in trap is placed over the nest and the whimbrel is trapped within minutes upon returning to incubate. The bird is held by one of the researchers while the harness for the satellite transmitter is custom fitted. After she is released and continues to incubate her eggs, the nest is monitored until the eggs hatch or fail; nest failure is usually caused by predation by arctic fox, raven, or jaeger. In both 2012 and 2013, nest success rate was near zero for whimbrels, but in 2014 it was a boom year. Over 50 percent of the nests hatched and many chicks were observed in the marshes. One possible explanation for the uptick is that there may have been a good number of lemmings in the nesting area in 2014. Although lemmings are tough to see in the marshy habitat, two were observed being captured in the Delta by a single parasitic jaeger, each within minutes of one another, suggesting that an abundance of prey allowed the whimbrels relief from the attention of the predators that had been feeding on shorebird eggs the previous two seasons.

Whimbrel nest. Most nests have 4 eggs and are lined with horsetail and grasses. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Adult whimbrel brooding a young chick. Video taken on Taglu Island, part of the Kendall Island Bird Sanctuary located in the outer Mackenzie River Delta. Video by Fletcher Smith.

A dark morph Parasitic Jaeger hunting the marsh. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Recently fledged Gyrfalcon chicks at the decommissioned communications tower site. Gyrfalcons are one of the few sources of adult whimbrel mortality on the breeding grounds. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Male Red-necked Phalarope incubating eggs. Video taken on Niglintgak Island in the outer Mackenzie River Delta during the 2014 shorebird field season.

After the nest monitoring and trapping of shorebirds is finished, we begin process of breaking camp, while excess food or gas is given to local people passing by on their way to hunting camps along the outer coast. Data is squared away and equipment carefully packed. With luck, the departure date will have good weather to avoid any delays home. The distant thumping of the rotors of a helicopter signal that our long journey back home has begun, and our hearts are glad with the anticipation of taking a hot shower and soon seeing loved ones.

Christine Anderson finishes browning a pizza with a propane heater. Photo by Paul Woodard.

Lots of mosquitos in the delta. These dense clouds make leaving the beauty of the delta easy to cope with. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The Arctic is characterized by plants with showy flowers, mosquitoes, and the routine threat of bad weather. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

The Low-centered Polygon habitat as we depart the delta. Notice the ridges are still apparent, but that the centers of the polygons have mostly dried. The delta quickly turns from frozen or flooded to vast expanses of green marsh. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Shortly after we leave field camp, the whimbrels will depart the Mackenzie Delta en route to their winter destination in Brazil to complete the loop on their astounding 14,000 mile annual migration. The tracking project has brought to light whimbrel behavior that challenges previously held beliefs about the migration routes of these birds. The overlap between the Mackenzie Delta population and the Hudson Bay population on the wintering grounds and Atlantic Coast staging areas was completely unknown prior to this study. Several critically important staging areas have been discovered because of this tracking project. The Center for Conservation Biology continues to lead whimbrel conservation research and plans are underway to work with these magnificent fliers in 2015.

Written by Fletcher Smith | fmsmit@wm.edu | (757) 221-1617

December 17, 2014

Learn More:

Fletcher Smith returns to the Arctic

CCB collaborates with Canadian Wildlife Service on arctic shorebirds