Virginia Hospitality: Realizing a vision

Camellia at Sussex County Landfill 9/27

September 27, 2013Camellia in New Kent County Sept 30, 2013

September 30, 2013

Nearly 20 years ago The Center for Conservation Biology, with funding from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, produced an educational booklet titled “Virginia Hospitality: Sharing the natural bounty of Virginia’s Eastern Shore with hosts of fall migrants.” The document focused on the lower Delmarva Peninsula with the primary message that we need to provide more habitat and food for fall migrants within this critical landscape. The booklet was an attempt to convey results from one of the largest migration studies ever conducted in North America to the general public.

Nearly 20 years ago The Center for Conservation Biology, with funding from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, produced an educational booklet titled “Virginia Hospitality: Sharing the natural bounty of Virginia’s Eastern Shore with hosts of fall migrants.” The document focused on the lower Delmarva Peninsula with the primary message that we need to provide more habitat and food for fall migrants within this critical landscape. The booklet was an attempt to convey results from one of the largest migration studies ever conducted in North America to the general public.

Devil’s walking stick is a common forest understory plant that provides important food for fall migrants along the lower Delmarva. Photo by Bart Paxton.

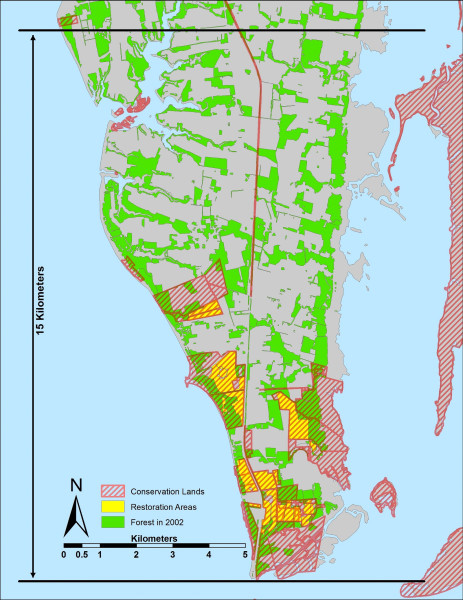

Today, conservation is literally growing across this important migration area. In recent years blocks of private land have been acquired by state and federal agencies for the purpose of restoring habitat for migratory land birds. This activity represents a sea of change in both the character and purpose of this landscape. In the heart of the most important staging area 290 hectares (715 acres) are undergoing the long restoration from agricultural fields to forest habitat. Over time, these lands are expected to support more than 750,000 bird days during fall migration.

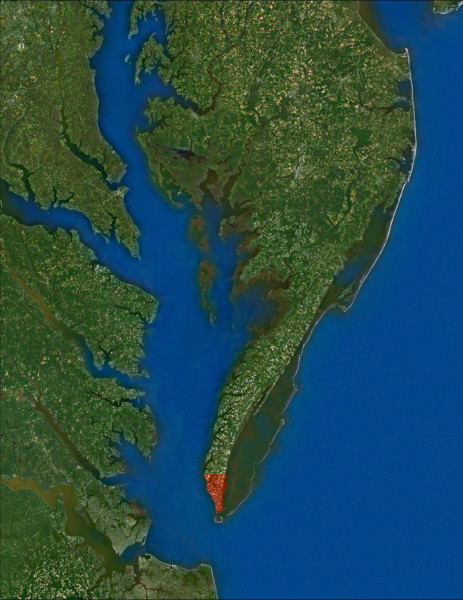

Map of the Delmarva Peninsula highlighting the area near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay where migrants reach their highest density. CCB has conducted a great deal of research within this area focused on guiding conservation efforts. Map by CCB.

The lower Delmarva and Cape May peninsulas are the most significant migration bottlenecks in eastern North America, concentrating large numbers of birds within relatively small land areas. Habitats on these peninsulas receive extremely high use by migrant landbirds during the fall months and are considered to have some of the highest conservation values on the continent. Along the lower Delmarva Peninsula, fall migrants “fall out” in the early morning hours as they reach the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and form a steep density gradient extending south to north within the lower 20 kilometers (12;..4 miles). For some species, densities are ten-fold higher near the tip compared to just 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) to the north.

Map of the lower 15 km of the Delmarva illustrating ongoing restoration efforts. Click on the map for a larger view. Map by CCB.

The ongoing habitat restoration along the Delmarva is a tremendous example of how conservation can and should work. Well-conceived and focused research was conducted to identify the highest priority management actions. The conservation community has come together and worked effectively to produce real conservation results.

Written by

Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 27, 2013

Related posts

A brood of osprey in Mobjack Bay showing a well-fed chick (left) and an emaciated chick (right). The chick on the right would die the following week due to starvation. Work in Mobjack Bay over a 40+ year period has shown that both reproductive rates and food delivery rates have declined dramatically. The decline in provisioning has led to an increase in brood reduction or chick loss due to starvation. Photo by Bryan Watts.