Great Blue Herons Rebound in the Chesapeake Bay

Camellia in Larkspur – Va Beach 9/21/13

September 21, 2013Second Osprey Reaches Cuba

September 23, 2013

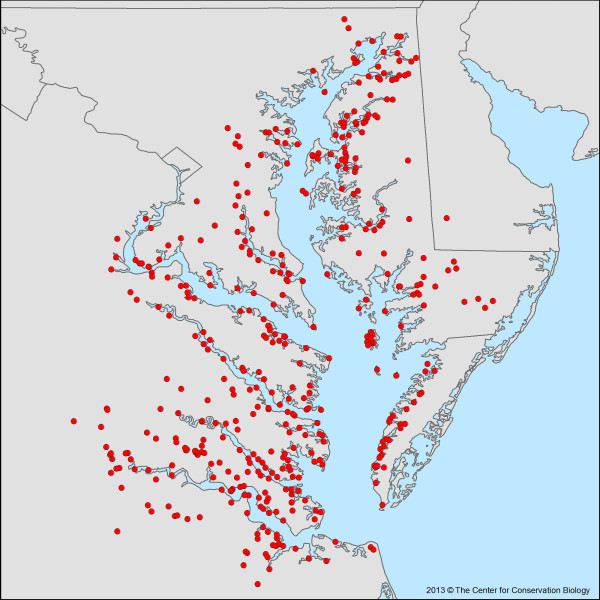

Breeding populations of great blue herons have made a dramatic comeback within the Chesapeake Bay according to a 2013 survey conducted by The Center for Conservation Biology. As with bald eagles and osprey, great blue heron populations suffered deep declines during the DDT era reaching a low in the late 1960s of approximately a dozen known breeding colonies. The 2013 survey documented 14,126 pairs within 407 breeding colonies making the species the most widespread and abundant breeding waterbird in the Chesapeake Bay. The population would consume an estimated 8,200 metric tons of fish annually. Colonies were documented within every county along the tidal reach of the estuary.

Map of great blue heron and great egret colonies along tidal tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay. Colonies were mapped and surveyed as part of a 2013 population assessment. Map by CCB.

An interesting finding of the survey is that the size of breeding colonies has been declining for more than a decade. The average colony size in 2013 was 35 pairs compared to more than 110 pairs in 1985. Large colonies that were stable for decades have begun to splinter and scatter across the landscape. Although the underlying cause of the decline remains unclear, one possible contributing factor may be the recovery of bald eagles. Bald eagles now nest in a growing number of heron colonies. The largest colony in the Bay on Pooles Island (1,450 pairs) now contains 4 bald eagle nests and the second largest colony on Mason Neck (1,250 pairs) now contains 2 eagle nests.

Wings of great blue heron in bald eagle nest with chicks along the Chickahominy River. Bald eagles may be altering heron colony dynamics. Photo by Bryan Watts.

In addition to great blue herons, the survey also included great egrets. More associated with coastal waters and never as common as great blue herons in the Chesapeake Bay, 1,775 egret pairs were found in 39 colonies. This number represents a nearly 3 fold increase in the population over the past 30 years.

Brood of great egrets in the lower Chesapeake Bay. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The 2013 aerial survey conducted by Bryan Watts and Bart Paxton required 200 hours of flying and covered more than 900 tidal tributaries of the Chesapeake. Funding for the survey was provided by the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, and The Center for Conservation Biology. The Center for Conservation Biology is a research unit within the College of William and Mary and the Virginia Commonwealth University.

Written by

Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

September 23, 2013

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts