CCB Transmittered Whimbrels in National Geographic News Watch

Azalea at Newport News Park 9/27

September 27, 2012Camellia Still at Naval Amphibious Base

September 30, 2012Tenacious Whimbrels Can Handle Hurricanes, Not Habitat Loss

Posted by Jeff Wells on September 25, 2012

Posted by Jeff Wells on September 25, 2012

Hurricane Isaac captured the country’s attention last month as it lumbered across Florida and raked over New Orleans, impacting millions of people. But before Isaac had even reached land, indeed while it was still not even a hurricane, many in the birding world were watching a single bird struggling against its high winds. I say “watching,” but in reality we were looking at regularly updated maps from the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) showing the location of the bird—a whimbrel—provided by a small satellite transmitter affixed to its back.

Whimbrels are unusual-looking birds, about the size of a chicken with long legs, brown upperparts and black head stripes. Their most striking feature is the long, down-curved bill. Whimbrels are birds of the shore, seen in North America feeding in salt marshes, on beaches, and on other intertidal marine coastlines. They are a surviving reminder of their smaller closest cousin, the Eskimo curlew, a bird now thought to be extinct; the last known individual was shot in Barbados in 1963. Eskimo curlews were killed in the thousands by market hunters in the late 1800s. The North American whimbrel population was estimated at 57,000 individuals in 2000, but their migration routes and timing were not well-understood. A few years ago, a CCB research team began catching spring migrant whimbrels along the southeastern U.S. coast and tagging them with satellite transmitters.

The initial results were amazing. Researchers found that birds flew all the way to Canada’s Northwest Territories to breed. One bird made a nonstop, 146-hour journey from the coast of Georgia 3,600 miles north to the Mackenzie Delta. In the fall, the tagged birds made similarly spectacular flights, to mangrove wetlands of the Caribbean and northern South America. On the way, they flew hundreds of miles over open ocean, often encountering hurricanes and tropical storms. Amazingly, only a single bird died in the process. Sadly though, two that had the tenacity to make it through hurricanes and tropical storms were shot and killed within days of arriving on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, where a tradition of shorebird hunting continues.

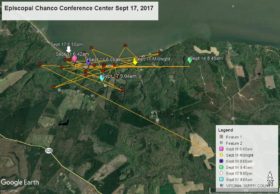

This summer, the CCB researchers made their own journey to the Mackenzie Delta, where they tagged a number of whimbrels at their nesting grounds. After departing the Northwest Territories, the birds beat their way eastward all the way across northern Canada to the Maritime Provinces on the east coast, refueled, and headed straight out to sea on a bearing toward Africa. They flew day and night, one of them for six days, until the westward winds pushed them to South America. One of the birds traveled nonstop for more than 4,000 miles!

Pingo was the nickname of the bird whose fate was being followed by many birders as, after several days of nonstop flight, she encountered the winds of Isaac. Slowed but not stopped or sent off-course, she landed on the coast of Brazil on Aug. 24. Since she was captured and tagged in June in the Mackenzie Delta, Pingo has traveled more than 8,000 miles.

If we needed a lesson about how conservation policies in one part of the world affect nature in another, Pingo and her feathered friends delivered it. Whimbrels can continue breeding only if they have healthy ecosystems in their two nesting regions—one that extends from the Mackenzie Delta to Alaska, and the other from the Hudson Bay to northern Manitoba and Ontario. Oil and gas exploration and climate change are causing major impacts. The Pew Environment Group and Canadian partners are working to protect these wetland habitats in the boreal forest and set standards for responsible development. Likewise, conservation advocates are working to protect habitat along U.S. stopover points. And although many wetlands where whimbrels winter in the Caribbean and coastal South America are under threat, migration studies like those described here put a spotlight on the places that need to be protected first. Let’s hope the amazing journeys of Pingo and her fellow whimbrels will make it easier to garner the public support in all nations to maintain the healthy ecosystems that we all need to survive.

Dr. Jeff Wells is a science advisor to the Pew Environment Group’s International Boreal Conservation Campaign.

2 Comments

Congrat’s CCB…Wonderful work you do . Love hearing about these amazing bird’s.Good flying Hope..Stay safe

Love the Whimbrel tracking, and the recent photo of Hope! I remember seeing what I think was a map of a whimbrel that visited the Pacific NW in an interesting shift, but I forget which one. I’m so curious, since many years ago I saw a bird (ufo!) in an aspen grove near Grand Coulee WA, that had a long curling bill. Wish I had a photo for a better description. It seems like entirely the wrong place for a curlew or whimbrel!