Peregrine falcon hack success

Azalea Has Returned to Mattamuskeet NWR

March 6, 2010Sea-level rise and tidal freshwater marsh birds

March 8, 2010

Written by Bryan Watts & Elizabeth Mojica

March 6, 2010

Rolf Gubler, NPS Biologist, placing a peregrine falcon chick in the hack box. Photo by National Park Service.

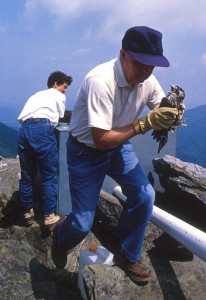

Rolf Gubler (right) of Shenandoah National Park monitoring the peregrine falcons once they have fledged. Chicks are banded with field-readable alphanumeric color bands which aid in their re-sight identification. Photo by National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) has partnered with the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) and other conservation partners to restore the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) to the central Appalachian Mountains. Since 2000, 90 wild falcons have been released, or “hacked,” in Shenandoah National Park (SNP). This reintroduction program is part of a long-term management plan to establish a stable breeding population in the Virginia mountains.

Currently, Virginia has 21 falcon pairs in the coastal plain but a mountain population that fluctuates between 0 to 3 pairs. A handful of breeding pairs have been established in the mountains as a direct result of the hacking programs. These mountain pairs face challenges from nest predators (raccoons and great horned owls), nest exposure during storms, and disturbance from humans.

Rolf Gubler holds a peregrine falcon fitted with a satellite transmitter by the Center for Conservation Biology before its release at the Shenandoah hack site. Photo by National Park Service.

The NPS hacking programs receive falcon chicks from bridge nests where fledging success rates are low (<5%). The mountain hack sites provide a safe fledging environment for the chicks hatched on bridges. Young falcons are removed from at-risk nests on the Virginia coast and placed in a hacking box on a secluded cliff in the park. A team of NPS staff and volunteers feed and monitor the falcon chicks in the hack box while being careful to keep human contact to a minimum. The door to the hack box is opened when the falcons are old enough to fly, around 45 days old. The young falcons continue to feed on quail provided at the hack site until they develop their own hunting skills.

Map of peregrine falcon dispersal from the individuals hacked at Shenandoah National Park (SNP), Virginia. Map by the Center for Conservation Biology.

The peregrine falcon restoration program at Shenandoah National Park began in 2000. Ninety falcons have been hacked from within the park at Hawksbill Mountain, Big Meadows, and Franklin Cliffs. Over the years the young falcons have dispersed into the surrounding states and established new breeding territories in Ohio, Pennsylvania, D.C., and New York. Two falcons returned to breed in Shenandoah: one on Stony Man Mountain from 2005-2007 fledging 8 young, and a second pair at Old Rag Mountain 2009-2010 which fledged 2-3 young in 2009 but lost their nest to a storm in 2010.

Six peregrine falcon chicks, growing larger in the hack box before they are ready to fledge. Photo by National Park Service.

Mitchell Byrd (foreground) and Amanda Allen Beheler prepare for a hack in the early 1990’s in Shenadoah National Park, Virginia. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

The breeding population of peregrine falcons has a tenuous hold in the central Appalachians. The National Park Service’s hacking programs are key to supporting the mountain population until it can become self-sustaining.

Project sponsored by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB), Shenandoah National Park (SNP), Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, (VDGIF), and Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), and the US Department of Transportation (US DOT).

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts