Eagle economics & the social burden of conservation success

Conservation in conflict: peregrines vs red knots

September 1, 2009Eagle economics & the social burden of conservation success

September 2, 2009

Written by Bryan Watts

September 2, 2009

Eagle nest in a large chestnut oak on a private estate along the Potomac River. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Survival of the majority of the endangered species in the United States will ultimately depend on our ability to manage habitats on private lands. More than half of all species listed as endangered have at least 80% of their habitat on private lands. In many cases, lands supporting endangered populations are either of high value or the basis of industries essential to local economies. Potential conflicts between species conservation and private property rights have become one of the central and most contentious themes in the development of policies involving endangered species. How to strike a balance between benefits to target species and the burden imposed on society has become one of the most complex problems in the recovery of many species. In many ways, management of the recovered population of bald eagles in the Chesapeake Bay will be a case study in how our society copes with the tradeoffs between a species that requires private property to persist and the right of owners to use their lands for economic or other benefit.

Bald eagles are sensitive to human disturbance. Since the 1970s, nest sites have been managed using a combination of spatial buffers and time-of-year restrictions. Human activities that are considered to be detrimental to breeding pairs (e.g. residential, commercial, and industrial development, logging, use of toxic chemicals) are restricted within a “primary buffer” and human activities that are considered to impact the integrity of the primary buffer (e.g. construction of high-density developments, multi-story buildings, new roadways) are restricted within a “secondary buffer”. Time-of-year restrictions are used to limit direct human activities (e.g. recreational activities, logging, mineral exploration) within buffer areas that may disturb eagles during sensitive periods of the nesting cycle. This dual approach to nest management continues to be the federal standard in the post-delisting era and is in use by most state agencies including Virginia.

Urban sprawl is moving down the Potomac River like a wave from Washington, D.C. and reducing habitat available for wildlife like bald eagles. Photo by Bryan Watts.

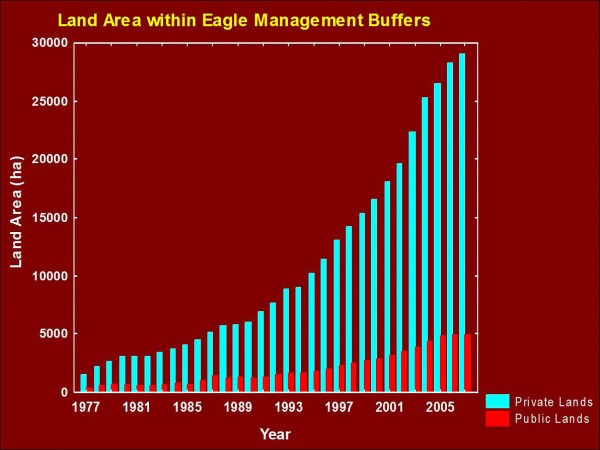

Since the 1970s, the bald eagle breeding population in the Chesapeake Bay has grown exponentially with an average doubling time of just over 8 years. The population has now recovered well beyond the size estimated during the 1930s, prior to the use of DDT in the Bay. More than 75% of pairs nest on privately-owned land and the availability of undeveloped waterfront property has become one of the dominant limiting factors for the population. One consequence of applying land-based restrictions to a rapidly expanding population is an increase in the burden borne by landowners to comply with such restrictions. Such opportunity costs for landowners arise when use restrictions prevent them from realizing economic or other benefits.

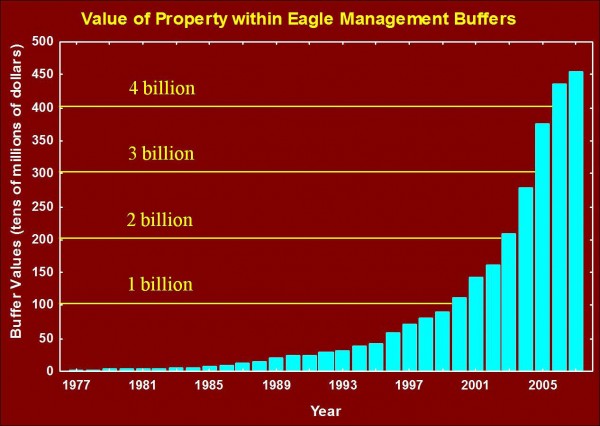

Increase in the collective value of lands within bald eagle management buffers on private lands in Virginia (1977-2007). Graph by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Over the past several years, The Center for Conservation Biology’s (CCB) biologists have been quantifying and monitoring the accumulated burden borne by private landowners related to bald eagle management guidelines by quantifying the area and monetary value of lands falling within management buffers. Although land value does not equate directly to the economic burdens borne by landowners, we believe that value does represent a reasonable surrogate. Due to growth in the nesting population, the area of private land falling within management buffers has increased from 2,500 acres to more than 55,000 acres in just 30 years. Over this same period, the collective value of these lands has increased to over 4.5 billion dollars. The density of breeding eagles varies dramatically across the lower Chesapeake Bay with most pairs breeding within rural counties. The value of land varies by more than 300 fold across the area with the most valuable lands occurring within the most developed locations. These relationships result in a large portion of the social burden being borne by relatively few landowners.

Increase in the collective lands within bald eagle management buffers in Virginia (1977-2007). Graph by Bryan Watts.

The market pressures currently operating within the Chesapeake Bay will make long-term protection of bald eagle habitat on private lands increasingly difficult. The economic burden on landowners is mounting and there is no mechanism in place for just compensation. How to reach an equitable compromise between eagle requirements and human impacts remains an open question. As eagle recovery moves from a biological to a social challenge, we must be willing to frequently reassess our approaches to find appropriate solutions.