Peregrine tracking project continues to produce new info

Enhancing pine landscape suitability for forest / early successional birds

October 5, 2008

Foraging distribution of cormorants & osprey on the James River

October 7, 2008

Written by Bryan Watts & Elizabeth Mojica

October 6, 2008

A juvenile peregrine falcon fitted with a light-weight, solar-powered satellite transmitter. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Peregrine falcon 54495 soars over a ridge in western Maryland in October 2008. Photo by Craig Coppie.

More than 20 years after the first re-nesting of peregrine falcons in the mid-Atlantic region, we still know very little about the ecology of this emerging population. In particular, we know almost nothing about the time period just after fledging. Several questions that are important to the future management of the mid-Atlantic population remain unanswered.

How many of the falcons produced in the mid-Atlantic survive to reproductive age? What are some of the causes of mortality? How and when do birds disperse from their natal sites? Where do birds produced in Virginia go to breed? Do birds in the Virginia population migrate? If they migrate, where do they spend the winter months?

During the spring of 2001 with several partners, CCB initiated project Falcontrak to track young peregrines during their formative period and hopefully to the winter and breeding grounds. To date the project has tracked nearly 50 young falcons and determined patterns of dispersal, mortality causes, migratory routes, and winter distribution. Birds have wintered from New England to Panama.

The latest phase of this work has been to track several falcons released in the New River Gorge. The young falcons are part of a program reintroducing the species back into the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia and West Virginia. Since 2002, CCB has transported 124 falcons to mountain hack sites in Shenandoah National Park, New River Gorge National Park, and Breaks Interstate Park.

New River Gorge hack site (red arrow indicates the white hack box from which peregrines are released to fledge). Photo by Bryan Watts.

In the summer of 2007, juvenile falcons were fitted with 24 gram solar-powered satellite transmitters allowing CCB and NPS biologists to follow their movements. Since their release at the New River Gorge, each falcon has flown between 10,000 to 22,000 miles ranging from Wisconsin south to Mexico.

One goal of the tracking project is to follow the falcons until they reach breeding age and establish a nest territory. Breeding could begin as soon as Spring 2009, thus tracking over the next few months is critical for locating a potential breeding pair.

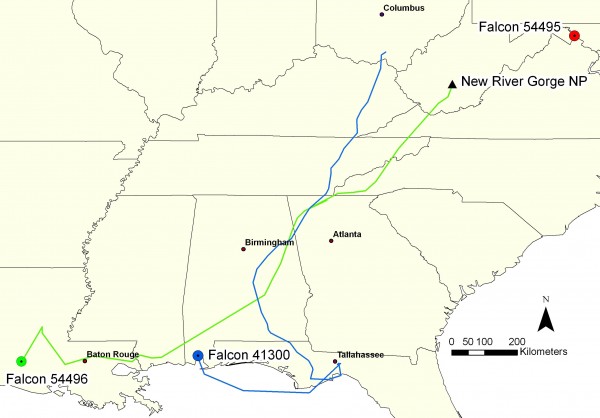

Fall 2008 migration of 3 peregrines: 54495 didn’t migrate and is wintering in western MD. 41300 left Ohio and is wintering in Mobile Bay, AL. 54496 is currently migrating west through Louisiana toward Houston. Map by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Related posts

Adult female from Elkins Chimney territory. Both the female and male were lost from this site between 2024 and 2025 nesting seasons and were not replaced. This territory has been occupied since 1995. Five territories were vacated between 2024 and 2025 along the Delmarva Peninsula in VA. Photo by Bryan Watts