The good hackers

Camellia at Carolanne Farms – Kempsville 6/29

June 29, 2013Camellia in Avalon Terrace – Va Beach 7/1

July 2, 2013

Centuries before the age of the computer and the development of the internet “hacking” was a technique that falconers used to build strength and hunting skills in their birds before actual training. Since the 1970s, the technique has been used as a management tool to ease birds into the wild for the purpose of restoring imperiled populations.

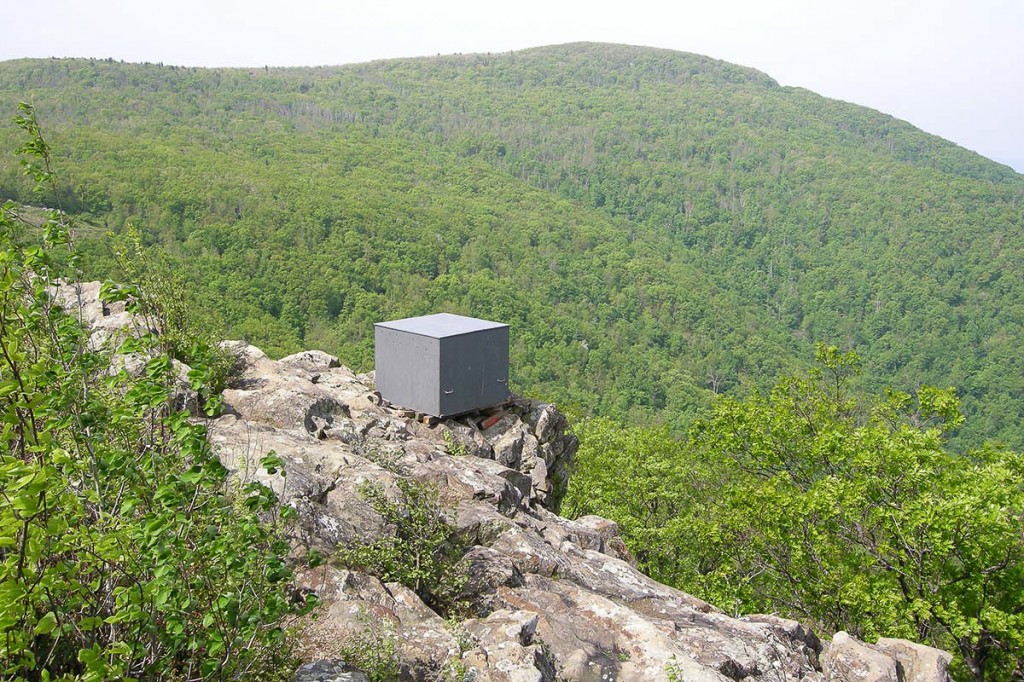

Peregrine hack box placed high on Franklin Cliffs overlooks the surrounding landscape. The front of the box is made with open bars mimicking the view of a cliff eyrie and allowing the young to imprint on the landscape. Shenandoah National Park photo.

The hacking process involves the use of a hack box to house birds during the preflight period, the release of birds, the provisioning of birds before and after fledging, and the monitoring of young falcons to independence. All activities are performed by a team of hack attendants. The “hackers” are critical to any successful reintroduction program.

Rolf Gubler (right) of Shenandoah National Park monitoring the peregrine falcons once they have fledged. Chicks are banded with field-readable alphanumeric color bands which aid in their re-sight identification. Photo by National Park Service

Since 1978, more than 420 peregrine falcons have been “hacked” in Virginia as part of a long-term management plan to establish a stable breeding population. Birds released in the first 15 years of this effort were from captive-breeding programs. This early phase of releases was successful in establishing breeding pairs on the outer coast and the state population has increased from none to more than 20 breeding pairs. However, the species has a very tenuous hold within the historic mountain breeding range with nesting pairs fluctuating from 0 to 3 annually. A continued reintroduction program is a key element in supporting the mountain population until it becomes self-sustaining.

Since 2000, birds released in the mountains have come from wild-reared birds produced by coastal pairs. The translocation program increases the survival of young from bridges, reduces the impact on migratory shorebirds and provides the opportunity to strengthen the mountain population. CCB and the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries have moved more than 200 wild-reared birds from the coast to mountain release sites.

Young male peregrine on perch after release in Shenandoah National Park. Shenandoah National Park photo.

The National Park Service has been committed to peregrine management in the mountains of Virginia and has performed the lion’s share of hacking activities. Hacking within Shenandoah National Park has been supervised by Rolf Gubler and would not have been possible without his leadership. Rolf has been committed to re-establishing peregrines in the mountains and has overseen hacking in the park for 14 years, releasing more than 110 birds. Some of these birds have dispersed to breed in Virginia and surrounding states. As with nearly all species, recovery of peregrines comes down to skilled and committed individuals.

Rolf Gubler transfers young peregrine with transmitter to hack box in Shenandoah National Park. Shenandoah National Park photo.

Written by

Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

July 1, 2013