Phragmites threatens tidal wetland habitats

Azalea remains in Northumberland County

September 14, 2009Back to Shores of Potomac River

September 18, 2009

Written by Bryan Watts, Bart Paxton & Fletcher Smith

September 14, 2009

The seaside sparrow is just one of many species of concern that breed in tidal high marsh habitats. Photo by Bart Paxton.

Close-up of Phragmites australis. Photo by Sebastian Hoppe/Wikimedia Commons.

Tidal wetlands are important to coastal ecosystems. They provide flood protection, erosion control and improve water quality. Tidal wetlands also provide essential habitats for numerous species of wildlife, many of which rely on these marsh habitats as a site for breeding and development. Historical wetland surveys indicate that as much as half of the marshes present along the Atlantic and gulf coasts in 1900 have disappeared. While direct human activities are still a leading cause of wetland loss, the structure and functioning of high marsh habitats are currently threatened from invasion of exotic, invasive plant species such as the common reed (Phragmites australis). Disturbance of habitat from dredging, filling, ditching, draining, and clearing, as well as the introduction of more invasive genotypes from the Old World, has enabled Phragmites to invade habitats where it was once absent.

Phragmites patch on the north end of Parramore Island, displacing native high-marsh and upland species. Photo by Fletcher Smith.

Stands of Phragmites are considered poor wildlife habitat and large, monocultures of Phragmites offer little habitat for birds and support few individuals and low diversity. The high marsh habitats which provide breeding habitat for several avian species of concern, including saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrows, seaside sparrows, black rails, and willets are most at risk from invasive Phragmites.

In 2006 and 2007, The Center for Conservation Biology initiated a study to determine the extent and degree of Phragmites invasion into the high marsh habitats of the lower Delmarva seaside and to determine the effect the invasion is having on the high-marsh breeding and wintering bird communities. We used a combination of high resolution aerial imagery and products from the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation – Division of Natural Heritage Phragmites mapping and monitoring project to access the extent and degree of Phragmites invasion. Transect counts in high-marsh habitats and along the high-marsh/upland edge were used to survey birds during both the breeding and wintering seasons.

Phragmites patches (light circles) grow like cancers in the marshes of Jamestown Island on the James River in Virginia. Photo by Bryan Watts.

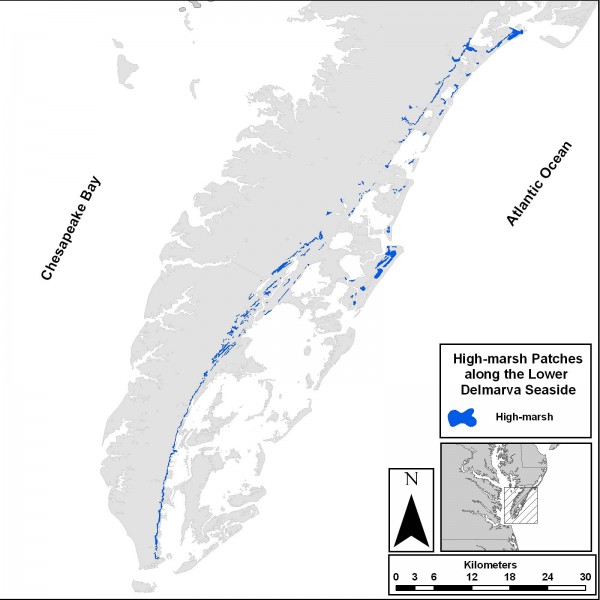

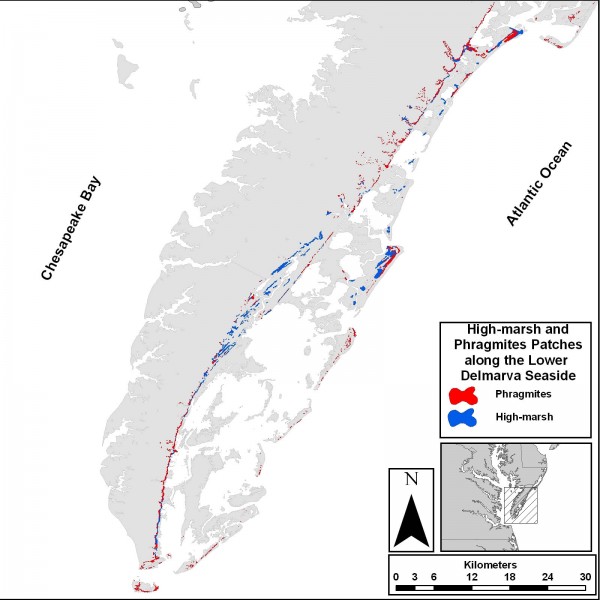

We found that of 264 high marsh patches identified, totaling 1,719 hectares, Phragmites had invaded 47% of the patches and was occupying 327 ha of high marsh, with high-marsh patches on the northern and southern ends of the peninsula exhibiting the greatest degree of Phragmites invasion.

High marsh patches along the Lower Delmarva seaside. Map by Bart Paxton.

High marsh Phragmites patches along the Lower Delmarva seaside. Map by Bart Paxton.

A total of 153,500 meters of transects were walked resulting in 4,314 bird detections, most of which were marsh birds. Many of the marsh bird species found, such as Willets, Nelson’s Sparrows, Saltmarsh Sparrows, Seaside Sparrow, Marsh Wrens and Sedge Wrens, are of high conservation concern. During both the breeding and wintering season, marsh birds did not avoid high-marsh patches that had been invaded by Phragmites, but they were rarely found directly associated with Phragmites habitat.

Phragmites has reached even the most remote areas of the Chesapeake Bay. Here, patches within the upper Chesapeake Bay, along the Delmarva Peninsula, green up before the surrounding marsh. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The majority of Phragmites invasion appears to be restricted to the extreme high marsh edge, along the high marsh/upland ecotone, and extending into the upland habitat. The current level of Phragmites invasion does not restrict the presence of high-marsh avian species. However, the abundance of high-marsh avian species is certainly reduced if Phragmites is occupying areas that otherwise would be high-marsh habitat. If preserving and reclaiming habitat for high-marsh avian species is a goal, it is recommended to prioritize Phragmites control and eradication efforts on large contiguous patches of high marsh, particularly on the northern portion of the Delmarva peninsula.

Project sponsored by The Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) and the Virginia Coastal Zone Management program (VA CZM).