Friend & Conservation Partner, George Kinter: World traveler, birder & book collector

Winter population count of red-cockaded woodpeckers

January 12, 2009Friend & Conservation Partner, George Kinter: World traveler, birder & book collector

January 14, 2009

Written by Carla Schneider

January 14, 2009

An avid bibliophile and birder with a long government career speckled with assignments abroad, George Kinter is a fascinating man to converse with. He’s a natural storyteller, weaving tales of global travels, bird-seeking adventures, with histories and relevance of individual volumes from his library together into a colorful tapestry. George has great pride in his grand collection of books on avian natural history, world travel, and species identification, and can expound upon the virtues and pitfalls of the authors and editors. The books range from the rare and curious to the trusted references highly valued by naturalists and birders.

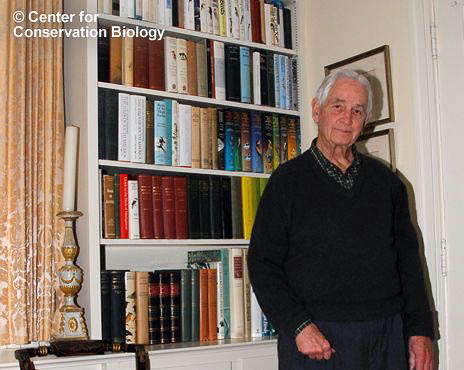

George Kinter, at his Maryland home with a portion of his John A. Griswold book collection. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

George Kinter’s connection to the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) began through CCB graduate student, Catherine Markham. Their friendship began through neighborhood dog walking interactions, and he took an interest in her research on bald eagles. Their many conversations about her eagle research and the other projects underway at CCB made a lasting impression on him. Having witnessed development and changing scenery in so many countries around the world, he is very interested in conservation, especially habitat protection, and supports CCB in its mission. Kinter has generously arranged a future donation of more than 400 volumes from his collection to The Center for Conservation Biology.

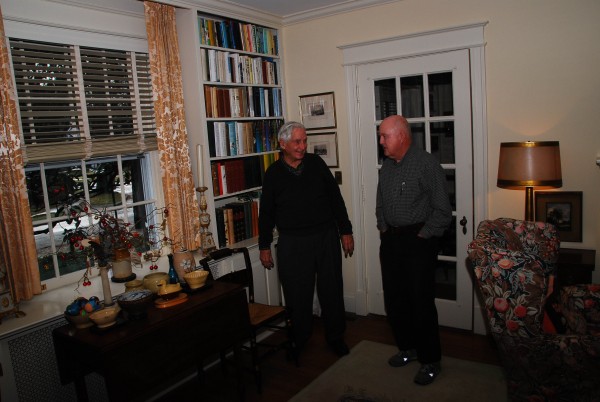

George Kinter discusses birding, global travel and his book collection with co-founder of the Center for Conservation Biology and ornithologist, Dr. Mitchell Byrd. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

The core of Kinter’s collection is the library of John A. Griswold (Gus), who was curator of birds at the Philadelphia Zoo. As George tells it, “[Gus] was a friend of Jean Delacour, the French ornithologist, and a number of the books I bought were autographed [from Delacour] to Gus Griswold. I learned of him when visiting the Atheneum [of Alexandria, VA] with my daughter many years ago. While there, I had asked the curator if they had any old bird books I could look at. A visitor heard me and said that if I was interested in bird books, I should get in touch with Gus Griswold, as he had lots of books. She even looked up his telephone number. When I finally got around to calling Griswold almost a year later, he invited me to see his collection, housed in the basement of an historic house near his. It took some time to arrange an appointment because the historic house was only open on certain scheduled days, but I was fortunate to meet him eventually and be able to make several visits about a year before his death. He told me with some pride that he had learned how to keep captive flamingos from loosing their pink color by feeding them shrimp shells, which provided the keratin they needed. He was a gentleman ‘of the old school.’ ”

After earning his BA in Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Queen’s College at Oxford University, George Kinter joined the U.S. Army, employed at map making, then joined the Foreign service. In 1958, he married Alice Wells of Charlottesville, VA. She gave him his first pair of binoculars (Navy surplus) in Eritrea, which served him well for several years. He notes that those binoculars have since been replaced (multiple times). Over the course of his career, Kinter was been employed by the U.S. State department (Consulate in Asmara, Eritrea; Consulate in Milan, Italy; Embassy in Nairobi, Kenya; Sinai Support Mission), then by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), where he worked on offshore oil issues and helped establish NOAA’s Damage Assessment Center. These varied assignments afforded George the opportunity to explore diverse habitats and hone his birding skills.

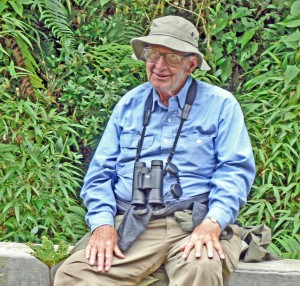

“A very tired me, taken on the Satipo Road during a birding trip to central Peru in 2007… after a long horseback ride down and back on a rocky mountain trail. It was a tough trip… But it was worth it.” – George Kinter. Photo by Alice Kinter

Kinter traces his interest in birding to his maternal great grandfather, George A. Boardman, a contributor of a wealth of ornithological specimens to the Smithsonian. Kinter relates his story: “My great-grandfather, [Boardman] was a lumber merchant in Calais, Maine, who traveled to Florida for his business in the late 1800’s. While there, he collected bird specimens for Dr. Spencer Baird, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute. There are some 250 of his skins in the museum’s collection, including Ivory Billed Woodpeckers and Carolina Parakeets (of the latter, he wrote that the species needed protection as they were so easy to shoot, the flock often returning to its fallen member). He had a small collection of stuffed birds at his home in Calais that included a Labrador Duck he had found in the Fulton Fish Market. His personal collection ended up in a small museum in New Brunswick, Canada.”

Twenty-day old peregrine chick from James River Bridge nest. Photo by Bart Paxton.

Like many seasoned birders, Kinter enjoys recounting birding challenges, unusual species and inspiring scenery. On Sinai Peninsula and in South Korea, he recalls having to cautiously avoid land-mine areas while birding. He has a theory that birders make the best spies, since they know the countryside well. During the two years in Nairobi, he spent time with a friend and Leica agent friend, John Camaley, finding that Kenya has especially good birdlife; one outstanding find in Kenya was a red and yellow barbit in a thorn tree. Kinter places Kenya high on his list of top birding locations. He is proud to have seen the nomadic Dead Sea sparrow near the Dead Sea. The rarest bird he has ever seen was the arequipa manakin, in Brazil, on a handicapped-accessible trail, no less! On a trip to Japan, he witnessed a breathtaking scene of Japanese cranes perched on dramatic rock structures protruding from mud flats. CCB’s work in Panama (see links below) especially interests him, since he has been birding in its wild Darien region. Kinter continues to travel, seeking-out birding hot-spots. He doesn’t intend to discontinue this quest soon.

George Kinter, like so many others of our natural history tradition, believes that birds have the capacity to greatly enrich our lifes experiences. The human connection to birds has become a common rallying point for conservation movements throughout the world. CCB and the greater avian conservation movement owe a debt of gratitude to George and the many others who have been inspired to make personal contributions to the research and education efforts needed for successful conservation.