Peregrine Clutches

Back to the Glades in Search of Black Rails

January 15, 2026Eagles and Catfish in the Chesapeake Bay

January 15, 2026By: Bryan Watts

1/8/26

Like other falcons, peregrines have strikingly beautiful eggs. Their eggs have splotches of color laid on a colored background. In the case of falcons, the color comes from the pigment protoporphyrin that is produced by glands within the oviduct just before laying. The background color gives peregrine eggs their “color impression” that varies from a vibrant pink to maroon to brick red to burnt orange. Females seem to produce eggs of their own unique color, and it is often possible to tell when a female has changed based on subtle changes in egg color. Egg color may also change throughout a clutch as a female begins to exhaust her stores of nutrition.

Peregrine eggs vary in color over a narrow range from pinkish to a brick red. Photos by Bryan Watts.

Because peregrine falcons were historically uncommon breeding birds throughout the southern Appalachians, little was documented about clutch size and other aspects of breeding. Prior to the DDT era, only five records of peregrine clutches were known from Virginia. These clutches were obtained by egg collectors between 1906 and 1936. Following reintroduction efforts and the first post-DDT nesting in Virginia in 1982, we have maintained intensive monitoring of the breeding population and filled in many gaps in nesting information including patterns in clutch size.

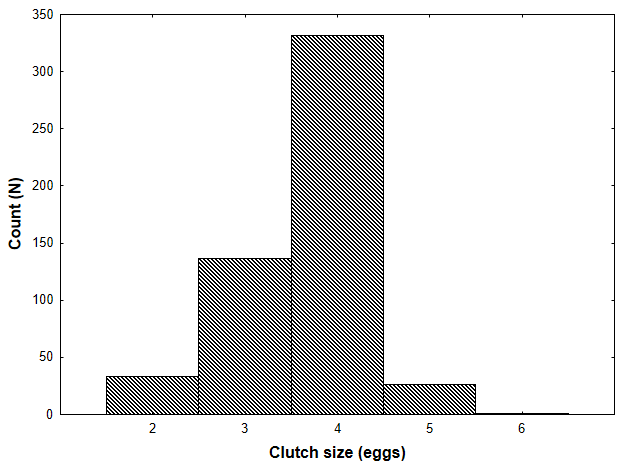

Since 1982, CCB and partners have recorded 530 complete clutches for peregrine pairs in Virginia. Over this time clutch size has varied from two to six. The modal clutch size is four eggs. Four-egg clutches represent 63% of all clutches. Three-egg clutches are also very common representing 26% of all clutches. Clutches outside of three or four are uncommon. Two-egg clutches represent only 6% of clutches and are typically laid by young females. Clutches larger than four are also uncommon and are typically laid by older females. Productivity begins to decline in females older than ten, and much of the decline is associated with lower hatching rates. Larger clutches may be a way for older females to compensate for lower hatching rates. It is common for older females to lay replacement clutches when none of the eggs in their first clutches hatch. Only one six-egg clutch has been recorded in Virginia and this clutch was produced by an older female on the Tappahannock Bridge.