Heron Heyday

Desperately seeking facts in a post-truth society

September 19, 2024

CCB and Partners Supporting Whimbrels Through Coordinated Conservation

October 9, 2024By: Bryan Watts

9/24/24

Many of us have nostalgia for the 1970s when sideburns ruled, Springsteen exploded on the music scene and you could buy a dozen eggs for 60 cents. But the 70s were more than 8-track tapes and skating rinks. In coastal Virginia, several factors seemed to have converged to make this period a high-water mark for wading birds (herons, egrets, Ibises). Some populations were building steam following recent range expansions into the area, while others were recovering from DDT or other insults. Whatever was in the water, the 1970s were a dream time for many waders.

For the years prior to the mid-1970s, systematic information on the abundance and distribution of waders in Virginia is patchy. Throughout the 1950s Jack Abbott monitored the Hollis Marsh mixed heronry on Nomini Creek along the Potomac, John Grey reported on a number of colonies in Tidewater and J. J. Murray visited several mixed heronies on the Delmarva. By the 1960s Fred Scott, Charlie Hacker and Walter Smith made annual visits to a couple of wader colonies on the Eastern Shore.

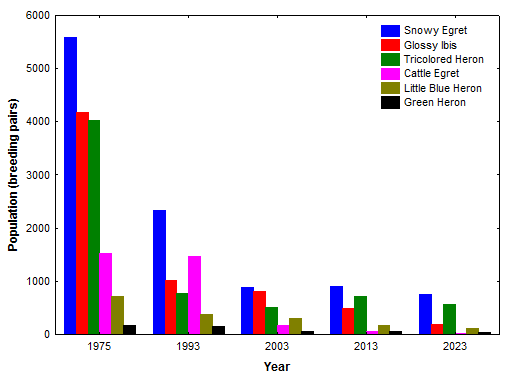

The quality of information on wading birds would take a turn in 1975 when Tom Custer and Ronald Osborn coordinated a systematic survey of wading bird colonies along the entire Atlantic Coast. Mitchell Byrd would lead the survey effort for Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. This survey represented an important benchmark for wading bird populations in Virginia. In 1992 a decision was made to survey breeding waders on a regular schedule (initially 10 years but later reduced to 5) to monitor trends. The survey was conducted in 1993, 2003, 2008, 2013, 2018 and 2023. This sequence of benchmarks allows for an assessment of trends in population size and distribution.

In retrospect, the 1975 survey was a peak for several waders in Virginia. Collectively, 6 of these species including snowy egret, glossy ibis, tricolored heron, cattle egret, little blue heron and green heron have declined nearly 90% from an estimated 16,204 to 1,659 pairs. First among these is the cattle egret that has declined >98% since the 1975 survey. The cattle egret was first found breeding in Virginia in 1961 during a period of rapid range expansion following first establishment in North America in 1953. In 2023 only 25 pairs were counted in three colonies. The glossy ibis has declined more than 95% since 1975. Glossies were first found breeding in Virginia in 1956 and rapidly built up to over 4,000 pairs. By 2023 they had dropped down to just 182 pairs.

Why have so many waders declined in Virginia over the past 50 years? Do these declines reflect larger patterns beyond the state or are they responses to local conditions? Answers to these questions are not completely known. One factor that has played a role is the loss of colony sites due to erosion and ongoing sea-level rise. We have lost several nesting sites to erosion since the 1970s. Since these species nest together in mixed species colonies, the loss of sites may have an impact on the entire community. Although it is unlikely that this single factor explains everything, it may provide a roadmap to management opportunities. Two species, including the yellow-crown night heron and the white ibis, have bucked the trend and actually increased in recent decades. Both of these species specialize on fiddler crabs and continue to expand their breeding range north with ongoing climate change. Populations of both species continue to build in Virginia. The white ibis was first found nesting in the state in 1977. Only 3 pairs were found during the 1993 survey. In 2023 we found 1,602 pairs in 6 colonies.