NEW PAPER: Breeding phenology of the eastern black rail

CCB surveys whimbrels along the Delmarva Peninsula in fall

October 4, 2021

Echoes of the Dough Birds

January 12, 2022By Bryan Watts

10/2/2021

Eastern black rails were listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act on 8 October 2020 and are listed as endangered in six states along the Atlantic Coast (Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia). The secretive nature of black rails, the difficulty in locating nests and their inconsistent appearance from year to year has resulted in a great deal of uncertainty about breeding status across their migratory range. Without confirmation of nesting, many observers have assumed that calling birds represent transients on their way to breeding grounds or extralimital, unmated males. The uncertainty is exacerbated by the fact that calling rates are highest in the pre-nesting period and decline as nesting is initiated. The confusion is deepened by the fact that males have significantly higher calling and response rates than females and that they utilize different call repertoires. This pattern of high detections early in the spring followed by fewer detections later in the spring has understandably led to a perception that early birds are not remaining to breed. Reducing this uncertainty is clearly important for clarifying the breeding range and interpreting historic detections.

The delineation of the breeding season for eastern black rails in relation to the spring and fall migratory periods is the focus of a recent paper published in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology:

Breeding Phenology of the eastern Black Rail (Laterallus jamaicensis)

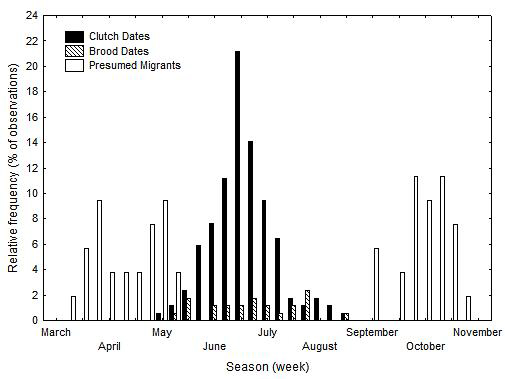

This study used historic records to evaluate the phenology of breeding and migratory periods in order to evaluate overlaps and exclusive periods that may be helpful in assigning breeding periods. Definitive breeding records (147 egg records, 23 brood records) were compiled from the literature, museum specimens and other sources over a 170-year period (1836-2016) to assess breeding phenology. In addition to breeding, records of “presumed migrants” were also compiled. Presumed migrants were individuals that flew into radio towers, lighthouses and tall buildings or were recovered from locations or structures known not to support breeding such as inner cities, ships at sea or offshore islands.

Nesting in eastern black rails extends for three months from mid-May through mid-August. Eggs have been recorded between 3 May and 15 August with a mean date of 20 June ± 18.5 days (mean ± standard deviation). Eighty-five percent of all clutches discovered were recorded during June and July. Adults with broods have been observed between 11 May and 22 August with a mean date of 26 June ± 26.8 days. Both migratory periods extended for two months. Seasons ran from mid-March through mid-May and early September through early November for spring and fall, respectively. Presumed migrants were recorded from early March through early May during spring and from early September through early November during fall, with mean dates of 15 April ± 22.9 days and 4 October ± 15.8 days, respectively. Breeding observations and records of presumed spring migrants overlapped during the first two weeks of May. The overlap includes only 2.4% of breeding records. There was no overlap between records of presumed fall migrants and the breeding season.

The vast majority of calling records of black rails from within northern latitudes where confusion about breeding status has been most pronounced have been after mid-May. Since spring migration is concluded during early May, these records are likely from birds that have reached breeding territories. There continues to be a general need to determine the residency status of birds across the migratory range using techniques that are independent of calling rates since birds appear to enter a “quiet” period as nesting begins.