Rogue states and the future of shorebird populations

Regulating Bunker – with osprey

July 13, 2021

60 years of bald eagle nesting data for the James River

July 14, 2021By: Bryan Watts

7/7/2021

One of the greatest challenges in managing migratory birds is that they exist within a legal quandary. As a recognized principle of international law, states have sovereign rights over all wild animals that fall within their jurisdictional boundaries but no jurisdiction over animals outside of these boundaries. The practical result of this principle is that animals that migrate from one jurisdiction to another are subject, in succession, to the sovereign rights and policies of all states along their migration route. Because a migratory population represents a single biological unit, successful management is not possible without cooperation among range states. This reality is what prompted the formation of international treaties and conventions to protect migratory species. The effectiveness of the safety net developed by these treaties depends on the level of participation achieved. Rogue or hold-out states may have outsized impacts on migratory populations regardless of the treaties and collective management programs established by cooperating states.

The loss of Machi and Goshen (two whimbrels being tracked by CCB) on 12 September, 2011 to hunters on Guadeloupe was a watershed event for shorebird scientists. The loss forced the conservation community to acknowledge that hunting within hold-out states could be contributing to ongoing declines of shorebird populations using the Western Atlantic Flyway. The event prompted the development of an international shorebird hunting working group focused on a long list of objectives including establishing and informing hunting policies, enforcement, quantifying harvest rates, outreach and education and the establishment of no-hunt preserves.

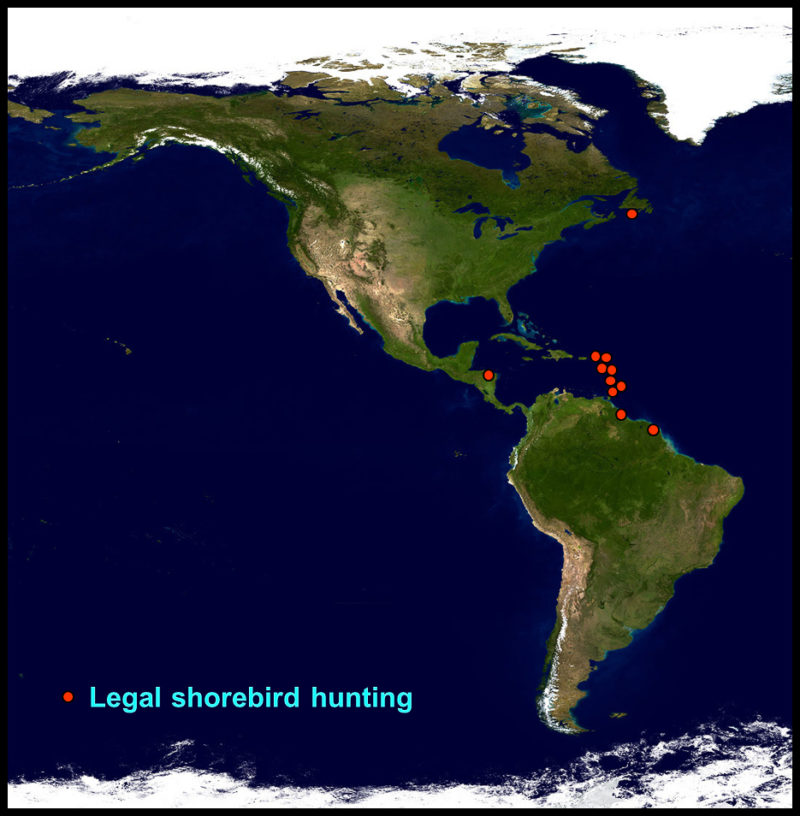

Over the past several years, CCB has published four papers that were intended, in part, to provide assistance to the hunting working group and to inform jurisdictions about the potential impact of their hunting policies. The paper “Estimating sustainable mortality limits for shorebirds using the Western Atlantic Flyway” provided estimates of the level of harvest shorebird populations could absorb. The clear message of the paper was that demography varied across populations and while some species such as American woodcock and Wilson snipe were appropriate for hunting programs, a long list of species could not sustain take and should NEVER be hunted. The paper “Assessing hunting policies for migratory shorebirds throughout the Western Hemisphere” examined current policies with respect to shorebird hunting for all jurisdictions throughout the hemisphere. This paper showed that 10 of the 11 jurisdictions where sport hunting of shorebirds is legal and practiced are exclusive to the Western Atlantic Flyway, and that 5 of these are overseas departments or collectivities of France. The paper “Seasonal variation in mortality rates for Whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus) using the Western Atlantic Flyway” demonstrated for one of the species most prized by hunters, the current mortality rate is unsustainable. The most recent paper “Whimbrel populations differ in trans-Atlantic pathways and cyclone encounters” demonstrates that populations differ in their migratory pathways such that some populations have exposure to hunting jurisdictions and others do not. This finding suggests that if harvest is focused on select populations rather than the entire continental population, then sustainable harvest limits are much smaller than previously believed as stated in the first paper.

Recently, Martinique (one of the overseas departments of France) released its proposed guidelines for the 2021-2022 shorebird hunting season to be brought up for a vote and adopted. The proposal is for the hunting season to extend from 25 July – 15 February, with hunting allowed every day. Bag limits have been outlined for several species that according to sustainable mortality limits should NEVER be hunted. Of note is that the bag limits are per hunter and for Martinique only, which represents but one jurisdiction that allows legal shorebird hunting. The bag limits and their mortality limits (based on continental population estimates) are as follows:

| Species | Bag Limit/Person | Annual Mortality Limit |

| Whimbrel | 2/day, 10/year | 1,210 |

| Hudsonian Godwit | 2/day, 10/year | 1,945 |

| Short-billed Dowitcher | 15/day, unlimited/year | 4,847 |

| Black-bellied Plover | 12/day, 50/year | 5,484 |

| Ruddy Turnstone | Unlimited | 7,124 |

| Greater Yellowlegs | Unlimited | 10,210 |

The conservation of migratory birds is by necessity a team sport where all of the players along the migratory pathway have a unique role to play. Success depends on everyone having a clear understanding of the stakes and a shared commitment to a common vision. All of the ingenuity, resources and efforts expended by the collective will come to nothing if one jurisdiction exercises their unilateral veto power. When the hunting issue emerged a decade ago there was considerable uncertainty about the role hunting was playing in the decades-long decline of some shorebird populations. Those days of uncertainty have faded into memory. Although several factors may be contributing to declines, hunting is prominent among them for several populations. Many stressors faced by shorebirds are beyond management control. Hunting is a policy decision. For some jurisdictions to continue to sanction recreational hunting of species that we now know cannot sustain themselves under the pressure is an affront to the many jurisdictions that continue to work hard for their recovery. If we continue down this path, the future of several shorebird populations will become increasingly certain.