Landscape dynamics along Virginia’s barrier islands: Assessing habitat stability for disturbance-prone species

Landscape dynamics along Virginia's barrier islands: Assessing habitat stability for disturbance-prone species

October 2, 2008Bald eagle communal roosts delineated in the Chesapeake Bay

October 3, 2008

Written by Bryan Watts & Michael Wilson

October 2, 2008

Barrier island systems contain some of the most naturally dynamic landscapes on earth. Along the mid-Atlantic coast, winter storms continually reshape these islands with strong waves and surges that shift sediments and overtop primary dunes. The Virginia barrier islands are the most pristine chain of barriers remaining along the Atlantic coast. These islands are subjected to an average of 38 extra-tropical storms annually, with enough intensity to rework beach sand and, as a result, have the highest beach erosion rate of any location along the Atlantic coast.

Rear dune area showing open habitat within a storm overwash area. This disturbance / successional habitat is critically important to many beach-nesting birds, such as the federally listed piping plover. Photo by Bryan Watts.

In recent years, it has become evident that the Virginia barrier islands are also the most important chain of barrier islands to colonial and beach-nesting birds in the mid-Atlantic region. Barrier islands contain unique habitats that are critical to the persistence of many colonial and beach-nesting bird populations.

Nest of piping plover in shelled portion of a storm overwash on one of the Virginia barrier islands. Photo by Bryan Watts.

Many of these species occupy a range of disturbance / successional niches that are defined by the relationship between beach erosion (due to storms) and beach recovery (via succession). A survey conducted by the Center for Conservation Biology in 1993 revealed that the site supported nearly 70,000 pairs of colonial waterbirds including 23 different species. The site supported more than 50% of the known Virginia population for 18 of these species and over 80% for 11 species. Seven of these species have been proposed for a status of “special concern” and 4 have been proposed for a status of “threatened” in Virginia. In addition to the colonial waterbirds, the site supports significant populations of the federally threatened piping plover, state endangered Wilson’s plover, and the largest breeding population of American oystercatchers known.

Over the past 25 years, populations of several waterbird species have declined dramatically within the Virginia barrier island chain. These declines represent not only a reduction in the number of pairs but also a reduction in the distribution of breeding sites. Some recent evidence strongly suggests that biotic factors such as mammalian and avian predators have played a role in species declines and distribution shifts. However, because the barrier island landscape is so naturally dynamic, it is difficult to eliminate possible shifts in habitat availability as a driving force. In order to reverse recent population trends, it was essential that the relative influence of abiotic (e.g. disturbance-driven habitat change) and biotic (e.g. predation) factors be separated within this system. Our objectives for this project were to characterize temporal and spatial patterns of beach habitats within the Virginia barrier island landscape and to quantify the relationship between landscape change and changes in the distribution of avian breeding sites.

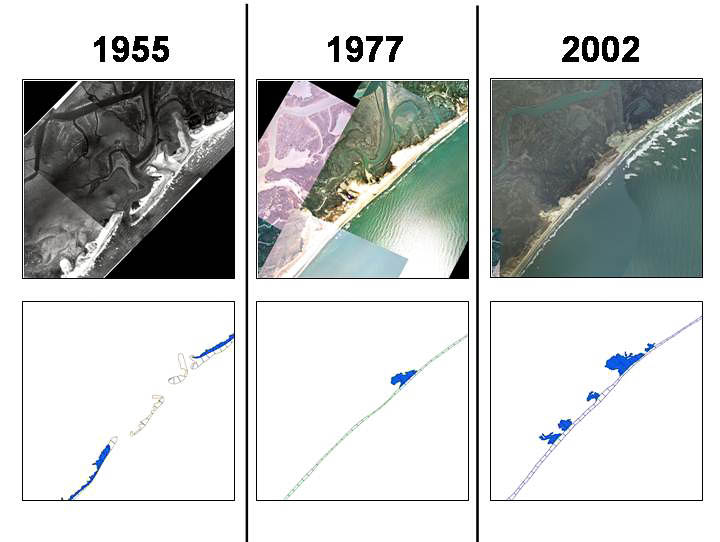

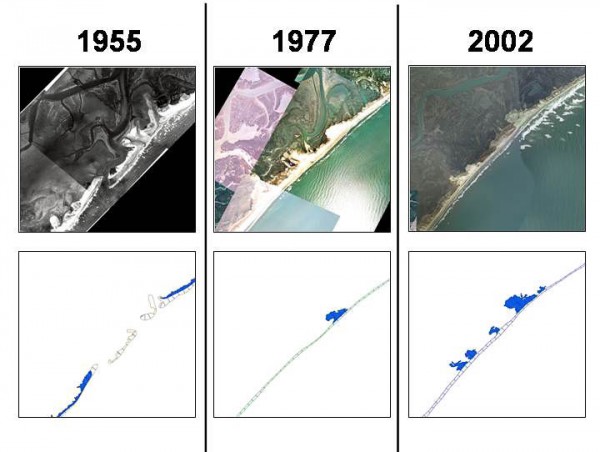

We began by creating a digital chronosequence of the islands using seven years (1949-2002) of aerial photos that were scanned, ortho-rectified, and placed in a Geographic Information System. Physical features of the active beach zone were then digitized from processed aerial photographs. Data on active beach area, beach width, distance to nearest wetland, habitat of beach-landward margins were compiled at island and sub-island levels and used to compare habitat use patterns of 4 colonial beach nesting species and 2 solitary nesting species.

Chronosequence of lower Smith Island, a Virginia barrier island. Storm washovers (blue areas), important habitat for beach nesting birds, have increased recently yet many species continue to decline. Photo by the Center for Conservation Biology.

Aerial photo of a washover of North Smith Island’s beach showing current direction (dotted), high tide line (blue), and overwash width (black). Periodic washovers create critical nesting substrate for certain species of shorebirds. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The distribution of colonial and solitary nesting birds was strongly associated with storm wash-over. Beach nesting birds use islands that are most frequently and severely disturbed. In general, birds used beach segments that were wider, closer to mudflats and other wetlands, and that had fewer stable dunes compared to areas not used. Photographic evidence suggests that the amount of habitat for beach nesting birds has fluctuated widely over the last 50 years but has actually increased in recent years. Based on this evidence, the recent declines of beach-nesting birds are probably better explained by factors other than habitat availability. This implies that other factors such as nest predation by ground predators as a leading factor responsible for population declines. This further suggests that conservation of beach nesting birds is not outside of our management control. There are several efforts underway to reduce nest predation on the Virginia barrier islands.

Funds for this project provided by a NOAA Coastal Zone Management Grant through the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality.