Eastern black rails in free fall

Grace at Bethel Landfill Newport News Jan 1, 2017

January 2, 2017Virginia peregrine falcons leap forward

January 5, 2017

The black rail is the most secretive of the secretive marsh birds and one of the least understood species in North America. Referred to by Alexander Sprunt as a “feathered mouse,” black rails rarely venture out from the rankest vegetation available. Because of their extremely secretive habits, the species was not recognized by the ornithological community as occurring in North America until Dr. Thomas Rowan captured an adult male with four young on 22 July, 1836 on his farm in Philadelphia and brought them live to Titian Peale. Later that fall, Peale would send the specimens to Audubon and they would be the basis of his plate on the species and a declaration of their occurrence on the continent. As additional specimens and observations were collected, a rough outline of their distribution would slowly unfold over the next century. Even today, what we know about this little rail is scattered in bits and pieces throughout more than 150 years of literature, museum specimens, and unpublished observations. One of the recurring themes echoed from the time of their initial discovery to the present is how frustratingly little we know about their distribution and ecology.

Photo of the elusive eastern black rail in typical habitat. The species typically remains below rather than above vegetation. Photo by David Seibel.

Concern for the eastern black rail population in North America began to build in the late 1980s and early 1990s, eventually leading to the formation in 2009 of the Eastern Black Rail Conservation and Management Working Group that has successfully brought biologists and agencies together around a common goal of collecting and sharing information for the purpose of developing a conservation strategy. Since the establishment of this group, targeted surveys (2014-2018) have been initiated on an unprecedented scale including new work in New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Texas. A high priority activity identified by the working group has been to locate, collect, and compile all information pertaining to the population with the intention of developing the historical context needed to inform conservation efforts moving forward. The Center for Conservation Biology completed this assessment in October of 2016. The treatment includes all states along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts (view report).

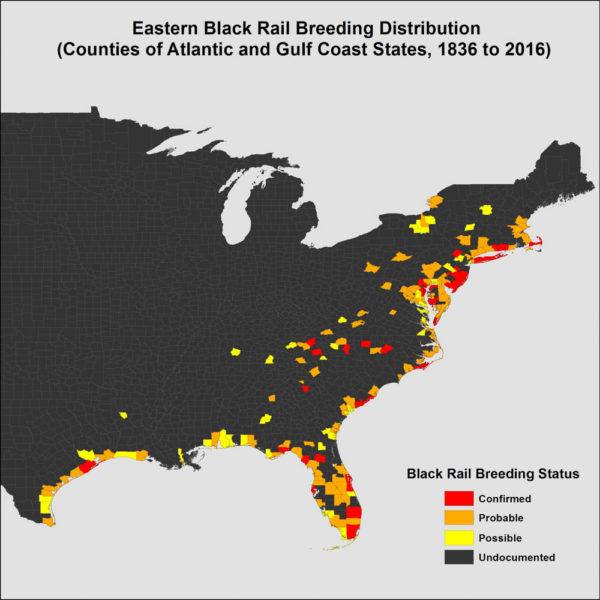

The historic breeding range of the eastern black rail appears to have included coastal areas from south Texas north to the Newbury Marshes of Massachusetts and interior areas west to the eastern slope of the Appalachian Mountains. Credible evidence of occurrence was found for 21 of the 23 states, including 174 counties, parishes, and independent cities and 308 named properties. Many of the named properties are well-known conservation lands including 46 national wildlife refuges, 44 state wildlife management areas, 26 state and municipal parks, and many named lands managed by non-governmental conservation organizations.

Map of counties with historic (1836-2016) credible records of eastern black rails during the breeding period (1 April through 31 August). Data from CCB.

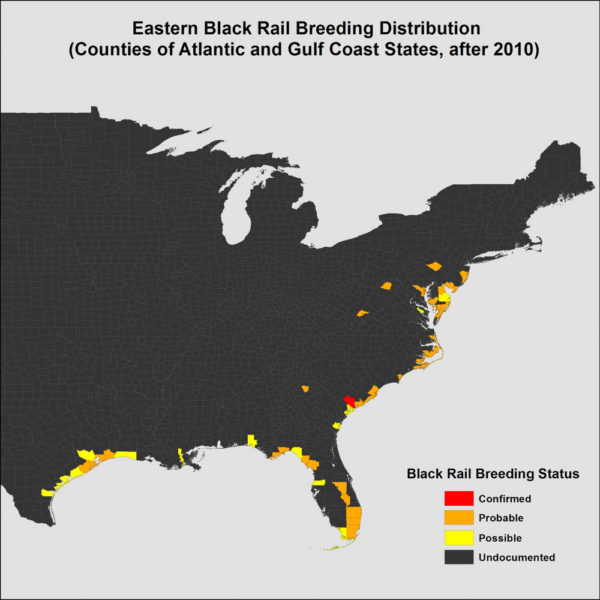

Black rails within northern areas have experienced a catastrophic decline including a contraction of the northern range limit from Massachusetts to New Jersey, a distance of 450 kilometers. Study areas in New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and North Carolina that were surveyed in the late 1980s and early 1990s and again over the past two years have documented a 64% decline in occupancy and an 89% decline in birds detected equating to a 9.2% annual rate of decline. Maryland has experienced a 13.8% annual rate of decline. South Carolina has experienced a 4.7% rate of decline for the same period. No information is available to assess trends for areas south of South Carolina.

Map of counties with recent (2011-2016) credible records of eastern black rails during the breeding period (1 April through 31 August). Data from CCB.

In addition to these broad-scale declines, one of the more disconcerting discoveries has been the virtual loss of the species from global strongholds. Elliott Island in Maryland has the distinction of representing the largest concentration of black rails ever documented when on 2 June, 1954, Terborgh and Knudson reported more than 100 calling birds. The site would attract bird watchers and biologists for the following 60 years. Counts have declined consistently and since 2010 peak counts have been one calling bird. In 2016 no birds were heard from Elliott Island. A similar pattern has been documented from Saxis Marsh, the historic stronghold in Virginia, where birds have not been detected since the summer of 2014. On Cedar Island in North Carolina where Rowlette and Wierenga recorded more than 80 calling birds on 27 May, 1973 only 4 calling birds were recorded in 2014.

Typical high-marsh habitat used by eastern black rails during the breeding season within the mid-Atlantic region. Photo by Bryan Watts.

The eastern black rail is listed as endangered in six eastern states and is a candidate for federal listing. The eastern working group has been actively pushing to fill information gaps throughout the range, to establish benchmarks, and to identify possible factors contributing to declines. The working group held a symposium during the Waterbird Society meeting in New Bern on 23 September that included six papers on recent findings from biologists working throughout the range.

Written by Bryan Watts | bdwatt@wm.edu | (757) 221-2247

January 4, 2017