Eagles Return to the Chesapeake Bay

Azalea in Great Dismal Swamp NWR 12/31

December 31, 2012Camellia at Bow Creek Golf Course New Years Eve

January 2, 2013Written by Bryan Watts

On June 20, 1782 the bald eagle was adopted as the emblem of the thirteen colonies and it became the symbolic representation of a new nation under a new government in a new world. Since that time, the bald eagle has arguably become one of the most recognized birds in the world. No other species has become more interwoven into the fabric of American life. The bald eagle has transcended its own biology to become a symbolic representation of freedom. The bald eagle was removed from the federal list of threatened and endangered species in June of 2007. This event formally recognized the greatest conservation success story in our nation’s history and declared the recovery of one of our society’s most enduring symbols. But how did we get here and what does this transition mean to the future of our eagle population?

As with wolves, bears, and lions, our relationship with bald eagles has not always been a favorable one. Whether through intentional or unintentional acts we have had a great impact on eagles throughout their range. During a time when predators were considered to be competitors for fish and game, the salmon lobby was successful in passing legislation in Alaska that established a bounty on Bald Eagles. Between 1917 and 1950, bounties were claimed on nearly 115,000 eagles. Although there was no bounty established in Virginia, the same sentiment was common and an unknown number of birds were killed under the banner of protecting fish stocks and domestic animals. Land clearing, overfishing, market hunting for waterfowl, and residential development all represent unintentional acts that collectively reduced eagles to lower and lower numbers in the Bay. However, it was the broad-scale use of pesticides such as DDT that was the last and deepest phase of this decline. Levels of DDT in Chesapeake Bay eagles were among the highest recorded for any population throughout their range. Without timely intervention, bald eagles would have certainly disappeared completely from the Bay.

There is no other place on the continent that represents this latest episode in our history better than the James River. During the 1950s there were 23 known bald eagle territories on the James. In 1962 the area around Jamestown Island was thought to support the highest breeding density of bald eagles in the entire Chesapeake Bay region. In 1963, an adult eagle was found under one of the nest trees on Jamestown Island. The bird was sick and trembling and later died. Chemical analysis revealed very high levels of DDT. In 1964, there were 13 pairs of eagles known on the James. The number dropped to 11 pairs in 1965, 7 pairs in 1966, 5 pairs in 1967 through 1969, 4 pairs in 1970, 2 pairs in 1971, and just 1 pair in 1972 through 1974. In 1974, the single pair laid no eggs. Over the 11-year period between 1964 and 1974, only 3 eaglets were known to be produced on the drainage. In 1975 there were no breeding pairs of bald eagles along the entire shoreline of the James making it the only major tributary of the Chesapeake Bay where the population went completely extinct.

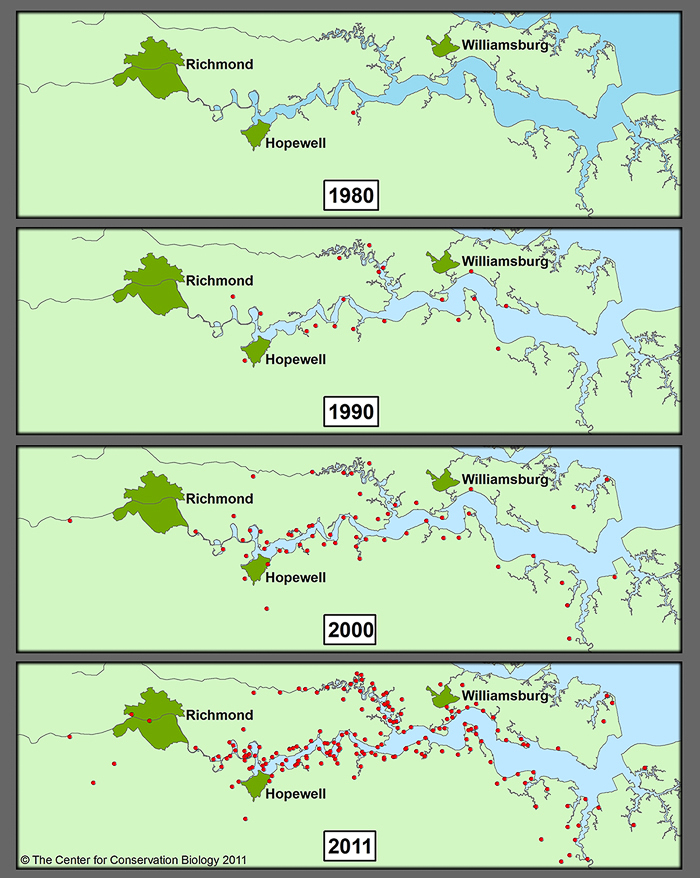

Bald Eagle nests on the James River 1980 – 2011. Map by CCB.

In 1979, just seven years after the federal ban on DDT, a single pair of eagles nested on Upper Chippokes Creek marking the first sign of recovery for this historic population. As with other locations, birds began to slowly re-colonize the James throughout the 1980s and chick production improved dramatically. In 1987, a nesting pair returned to Jamestown Island, a full 25 years after a breeding adult died of chemical poisoning. In March of 2002, we conducted a historic survey flight that documented 81 breeding pairs along the James. Though this event was marked by only a few of us at the time, this survey represented a conservation milestone when the James River supported more pairs than the entire Bay just 25 years before. During the spring of 2012, the James supported 190 pairs of eagles that produced a record 241 chicks.

The population recovery documented on the James has been repeated throughout most of the bald eagle’s former range. The Virginia population has increased by nearly 40 fold from a low of 20 pairs to more than 800 pairs. The collective number of pairs in the lower 48 states has also shown a dramatic recovery. Success on this scale has led to numerous debates about the need for further management and expenditures. During a time when funding for such activities is stretched beyond reason, these debates inevitably lead to discussions about the inherent value of species to society at large and the costs of conservation.

I am asked with regularity “why should we be concerned about a particular species or place?” or “what is their value to society?”. The obvious answer to this question is that our society has expressed the value that we place on bald eagles by the millions of dollars and hours that we have expended on its behalf. However, the true answer is that bald eagles like so many other things do not conform to the value metrics that our society has become accustomed. What is the “value” of watching a brilliant sunset in autumn or to look up from the floor of the Sistine chapel to see one of the greatest achievements of mankind? Do these experiences not enrich our lives beyond measure? I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with a magnificent species during a period of remarkable recovery. Although I vividly remember observing my first eagle in the wild, I am too young to have experienced the silent years. Ask the watermen who have worked the waters through this period how the return of this species has lifted their daily lives. Ask the scores of private citizens, professionals, and conservation groups who have spent countless hours with their shoulders to the plow to pave the way for this recovery. They will tell you that the sight of this bird on the wing is more than payment in full for their efforts. As eagles become more common in the Bay the dividends of these investments enrich us all. They symbolize the recovery of our common heritage.

For thousands of years, bald eagles have nested along the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. Like few other species, they have born witness to the many changes in the Bay. They have seen the shoreline redrawn many times through the rise and fall of oceans and forest types move across the landscape as climates have come and gone. They have smelled the smoke rising from a thousand cook fires. They have witnessed the English sail into the mouth of the Bay and heard the sounds of revolution. In recent decades they have seen roadways and development reach out to every corner of the watershed. Yet they remain, the most inspiring consumer within one of the most fertile aquatic ecosystems on earth.

1 Comment

What happened to the tracking of Azalea and Cammelia which was being done by Reese