Then and now: A look back on osprey breeding performance in the lower Chesapeake in the late 1980s compared to today

The Resurgence of Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers in Virginia

February 5, 2025

2025 Field Season to investigate osprey metapopulation dynamics in Chesapeake Bay

April 5, 2025By: Bryan Watts

1/17/2025

For over twenty years (1970-1990) Mitchell Byrd monitored the osprey breeding population in coastal Virginia. The monitoring effort was a partnership between William & Mary and the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries (now Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources). The effort was expansive, covering several hundred pairs annually by both plane and boat to track changes in the population (number of breeding pairs) and breeding performance (number of young produced per pair). Through the years, Dr. Byrd involved seven graduate students (Bob Kennedy, Gary Seek, Chris Stinson, Jerry Via, Kevin Roberts, Tim Kinkead and Peter McLean) and many undergraduate students in osprey research. Many research topics were addressed by students including nesting behavior and phenology, diet and provisioning, chick growth, dispersal and adult age structure, and contaminant exposure. In addition to student projects and population monitoring, many conservation efforts were undertaken including providing young to other states to re-establish breeding populations and the design and testing of artificial nesting platforms. Dr. Byrd involved many volunteers in monitoring efforts and was an osprey conservation ambassador for the many people living around the lower Bay.

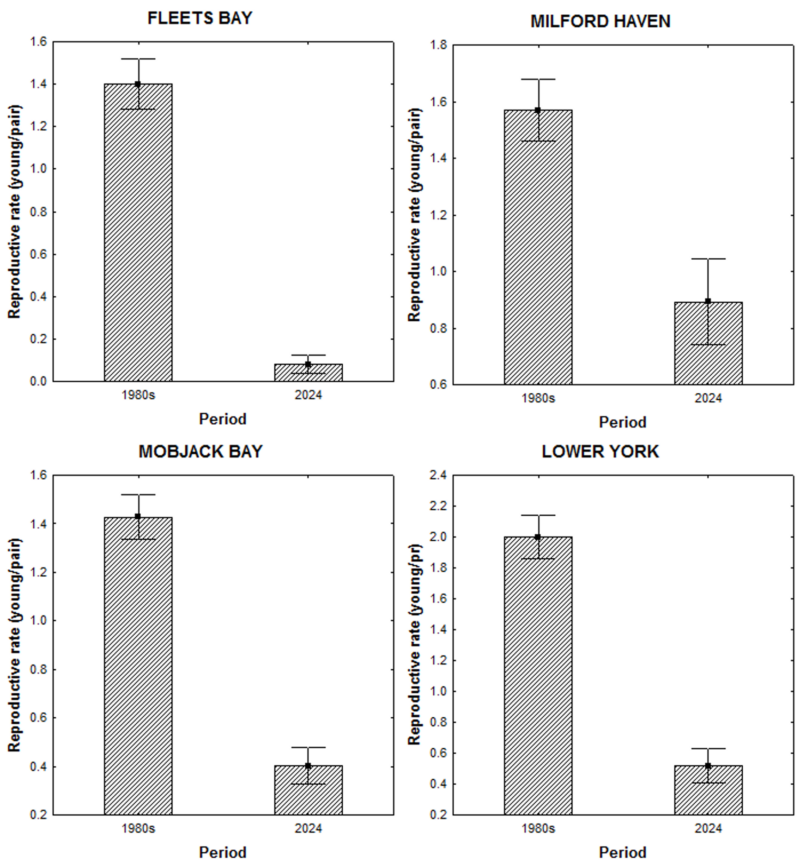

The original osprey monitoring project left behind a tremendous legacy of data (housed at CCB) that has ongoing value to generations of researchers. Recently, I have looked back and compiled data (1985-1988) from four study areas (lower York River, Mobjack Bay, Milford Haven-Piankatank, Fleets Bay) to make comparisons to data collected in 2024.

All of the study areas tell similar stories. Performance was poorer in 2024 compared to the 1980s for all metrics of breeding. Thirty-seven percent of all pairs in the four study areas did not lay eggs in 2024. This compares to only 1.7% of pairs during the 1980s. For pairs that did lay eggs in 2024, 69.1% failed compared to only 24.2% during the 1980s. Pairs that hatched eggs in 2024 lost on average 1.02 young before fledging compared to 0.36 young in the1980s. Loss of young through brood reduction resulted in lower brood sizes at fledging. Average brood size was 2.04 in the 1980s compared to 1.5 in 2024. All of these metrics leading up to final reproductive rates have driven a 3-fold difference in productivity. Pairs within the four study areas produced an average of 1.55 young compared to only 0.46 in 2024.

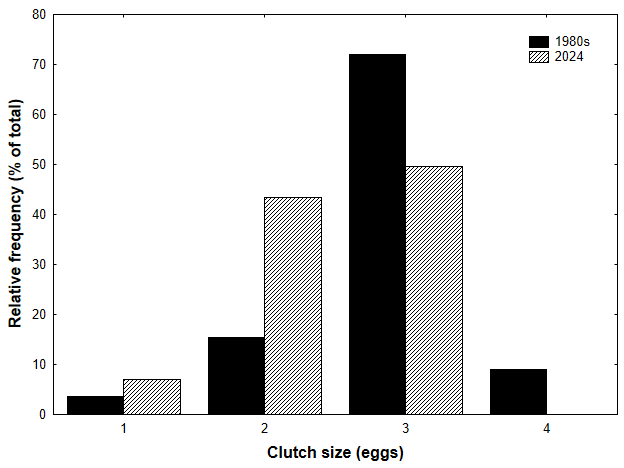

Likely the most unexpected observation during the 2024 season was the large number of females that never laid clutches. These pairs arrived from winter grounds on time and remained resident in territories throughout the nesting season but never laid eggs. A likely explanation for this behavior is that females did not get enough fish to reach the condition required to lay. One of the most unexpected comparisons back to the 1980s is that average clutch size had declined. Average clutch size during the 1980s was 2.86 compared to only 2.42 in 2024. During the 1980s, more than 80% of recorded clutches contained 3 or 4 eggs. In 2024, less than 50% of clutches contained 3 or more eggs. Smaller clutch size may be an indication of food stress.