Dune Foragers: Unraveling the Ipswich Sparrow’s Hidden Diet

The Arc of Conservation

February 5, 2025

Deja vu all over again: Tracked eastern willet shot on Guadeloupe

February 5, 2025By: Chance Hines

1/15/25

The Ipswich sparrow, a denizen of Sable Island, Nova Scotia during the summer and coastal dunes along the American Atlantic Coast in the winter, has been a focal point of CCB’s winter bird research for years. Despite long-term studies, many questions about the species persist. Fortunately, advances in areas like DNA metabarcoding are providing new insights into how these habitats support the sparrows.

Initial research into Ipswich winter ecology pioneered by Stobo and McLaren in the 1970s suggested that American beachgrass was the most critical plant for Ipswich sparrows. However, more recent survey efforts by CCB have revealed a stronger association with various forbs, including seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), primrose (Oenothera humifusa), and buttonweed (Diodella teres). These forbs retain seeds well into the winter, potentially providing a crucial food source during the colder months. Notably, Ipswich sparrows have frequently been observed foraging on seaside goldenrod inflorescences, though this may be partly due to the tall, conspicuous stems that make them more visible in the landscape.

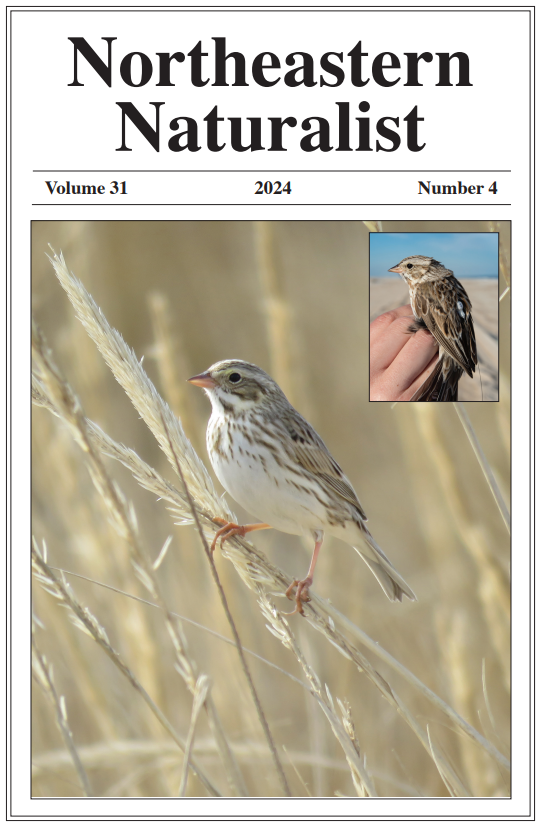

The results of a recent CCB Ipswich sparrow tracking project were recently published in Northeastern Naturalists and identified areas where both forbs and shrubs were available as those that Ipswich sparrows were more likely to occur. This article also documented sex related differences in habitat use. These differences included larger home ranges for males who were also more likely to be found nearer the active beach. We hypothesized that these differences might stem from food preferences, with dominant males and adults favoring the more patchily distributed American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), while younger birds and females rely on a more diverse diet of grasses and forbs that are more likely to be located in dunes further from the beach.

In an effort to resolve the question of what comprises the birds diet, Assateague National Seashore, CCB and North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences teamed up to capture birds, collect fecal samples and analyze those samples for DNA of the birds prey items. The results of this analysis were consistent with our hypothesis but still quite surprising. Females did have a broader diet (13 plant species for females vs 7 plant species for males) that included more forbs than males, and males did focus much more heavily on a grass species found in dunes. However, the grass species most often identified in fecal samples was not American beachgrass, as many would have thought. American beachgrass was only detected in three of 77 fecal samples while purple sandgrass (purpurea trilapsis) was detected in 31 samples. Other plants commonly found in Ipswich diets were seaside goldenrod (11) and evening primrose (7).

Purple sandgrass has rarely been observed along survey transects during winter, possibly because the above-ground portions of the plant are sheared from the roots by howling coastal winds after the growing season. Unlike other dune grass species which support seed heads into and throughout winter, purple sandgrass drops almost all of its seeds onto the ground well before winter. Interestingly, this plant species produces seeds of variable size and retains the largest seed it produces which is hidden within each dead tiller (or stem) throughout the winter. It is not clear whether Ipswich sparrows have figured out how to extract these seeds from the plants holding them or if they are keying in on seeds dispersed into the dunes and then blown into the paths of foraging Ipswich sparrows, but this plant is clearly important to Ipswich sparrows on Assateague Island.

Identifying this species as the most important contributor to Ipswich sparrow diets has conservation implications. Beach planting initiatives meant to stabilize dunes throughout the coast primarily focus on a single species, American beachgrass. It is thought that planting this species also benefits birds and other animals by providing seeds for them to forage on. Including purple sandgrass, as well as other forbs, in these plantings would likely provide a greater benefit for Ipswich sparrows and potentially other birds and small mammals of the dunes that depend on seeds during winter. CCB’s continued studies of Ipswich sparrows highlights the complexities of understanding the dietary needs of cryptic species, particularly in dynamic and harsh environments like coastal dunes. The unexpected prominence of purple sandgrass in the sparrows’ diet underscores the importance of considering a diverse range of plant species when managing and restoring dune habitats. By broadening conservation efforts to include species like purple sandgrass alongside traditional plantings of American beachgrass, we can better support the ecological needs of Ipswich sparrows and other wildlife that rely on these ecosystems during the winter months.