Saltmarsh Sparrows Surviving Virginia’s Winter Weather

Divergence in Virginia Peregrines

March 29, 2023

CCB and Saltmarsh Bird Surveys

June 1, 2023By: Chance Hines

3/29/23

For the sparrows of the marsh, the worst of winter has passed. In Virginia, the 2022-2023 winter was relatively warm, but temperatures did approach single digits in coastal areas during late December. That cold weather system brought plenty of wind and ice to marshes where these birds make their home. Blustery conditions like those could mean death to birds that are unable to cope with the weather.

In order to survive harsh winters, these birds must find a patch of marsh that provides the basic requirements in life, food and shelter. The lower elevations of suitable marshes provide areas for sparrows to forage on seeds gleaned near the muddy surface and the higher portions provides safe places to wait out high tides that inundate the lower marsh twice per day, as well as access to areas that can provide shelter during the harshest winter weather.

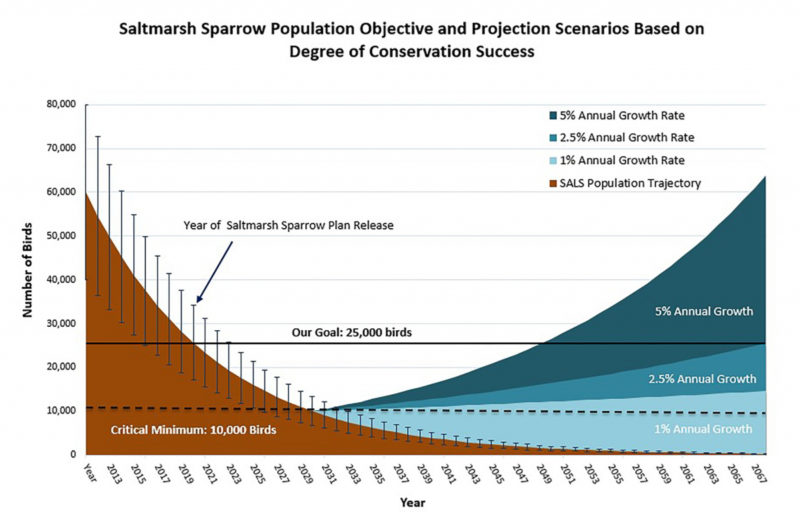

Biologists from The Center for Conservation Biology and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service have used the higher portions of marshes to capture birds roosting during high tides for the past three winters at the Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge. The focal species for this study is the saltmarsh sparrow, a taxon that is likely to be listed on the threatened and endangered list in coming years. Researchers estimate that the species is declining 9% annually and could be extinct by 2035 if the current trajectory continues. Like many other terrestrial species, sea level rise is presenting a hurdle to their existence and researchers throughout their range are rushing to address various issues that may be confronting the species.

Tidal flooding associated with increasingly high tides is lasting longer and occurring more frequently. Tidal flooding during the summer breeding season is thought to be the primary driver for the documented portion of the saltmarsh sparrow’s decline. However, negative effects resulting from greater severity of tidal flooding may not be limited to the summer breeding season for birds that use the saltmarsh. Higher tides may also have a negative effect during winter when the highest tides are often associated with strong winter storms that bring along frigid temperatures and howling winds.

The highest winter tides can flood even peak elevations on many of the marsh islands along Virginia’s coast, compelling birds that typically use these lower lying island marshes to flee to marshes where suitable roosting habitat is available. The marshes with the most available roosting habitat are those along the mainland edges and larger barrier islands. The marshes surveyed as part of this project are all areas adjacent to higher ground with larger shrubs and trees that offer roosting habitat and serve to reduce exposure to wind that scours seeds from plants.

Capture data seems to support the idea that birds move to these more protected marshes in harsher winters. More birds are captured at these sites at the end of a harsh winter than at the beginning, possibly because many birds that typically use lower lying marsh islands are forced to the mainland study sites. During the warmest winters, the number of captures declines the most throughout the season at these inland sites, possibly because birds are able to stay on the smaller marsh islands. Now that temperatures are warming, invertebrate prey items are becoming more abundant, helping to fuel these species as they prepare for their annual northward spring migrations. While the birds bustle to secure their place on their breeding grounds throughout the North Atlantic, CCB will be taking a closer look into the data to sort out how our findings can be best utilized to help inform management decisions for these vulnerable birds.