Chasing Black Rails

Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers at Peak Population Size in Virginia

September 30, 2022

Ripening Fruits Fuel Migrating Songbirds

October 6, 2022By: Bryan Watts

10/4/22

It is 2:30 on an April night in 1993 and I am standing on the edge of the Guinea marshes along the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay. I am using a small cassette player with a nine-volt amp to survey for black rails. The night is black with only a lone horned owl calling from a distant tree line. As the call sequence ends, I close my eyes and strain to listen. Just as I begin to turn for the walk out, a black rail fires up (ki-ki-kerr) at the top of his voice from between my boots. Few things will get your heart pumping like the blast of a rail underfoot in the dark. A month later, my heart is racing again as I push my way after midnight through large patches of black needlerush in Saxis marsh. Armed with a box of white owl cigars to discourage the throngs of mosquitoes, I have come to sort out the number of calling rails within a regional stronghold. The air was heavy but still over the marsh, and the marsh was alive. The orchestra of sound was right on with the usual suspects coming in on cue. Walking out of the marsh all seemed as it should be.

The status quo encourages complacency. Throughout the 1990s, reports of black rails seemed to be from the right places and the red flags were hanging limp. But by the early 2000s, the disappearance of rails from many places and lower numbers from strongholds made it clear that black rails were in trouble. By the mid-2000s, all the red flags were flying and CCB held several internal meetings to discuss options. The situation was complicated because black rails are so secretive. Status had not been resolved throughout much of the range and habitat requirements were poorly understood. Among other actions, CCB decided to assist in resolving status throughout a portion of the range in order to determine what areas were still viable to be worked.

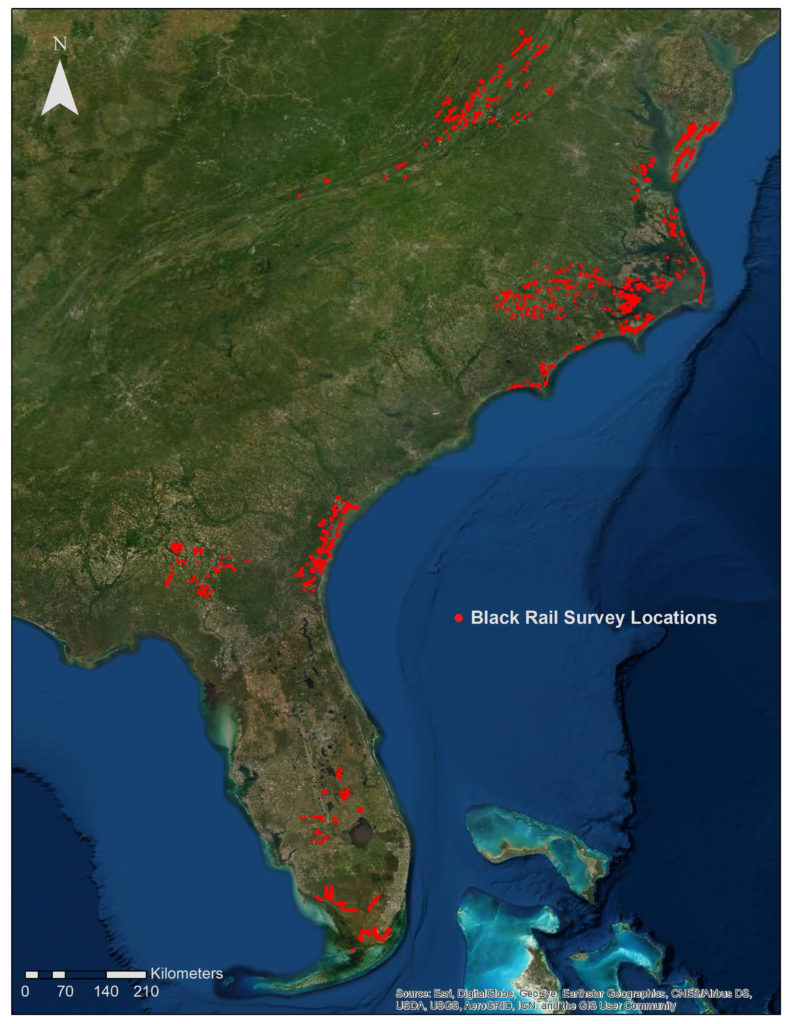

Since we initiated work with black rails, CCB biologists have established 3,500 survey points across four states and conducted more than 12,000 point counts. Sadly, the surveys have mostly determined that black rails have disappeared from locations where they occurred historically. We have begun each survey with anticipation and the hope of uncovering a nook or cranny with a hidden gem, but have ended with a gathering sense that few places remain to be resolved and fewer still now support black rails. All is not as it should be. But we continue on, chasing a moving target through the night marshes. The path to our understanding of secretive and rare species winds its way through scores of empty dead ends.

Surveys alone will not turn the tide for species like black rails that are falling. Changing their trajectory will require active management to restore and create suitable habitat. However, surveys inform decisions along the way that are essential to command and control of conservation activities.