Flying into the “Bay of the Dead”

60 years of bald eagle nesting data for the James River

July 14, 2021

Trapping eagles

October 4, 2021By Bryan Watts

10/1/2021

After landing on an unmanned airstrip and filling the tanks with three jerry cans of 100 LL, we had the evening to review maps and contemplate the flight for the next day. Bahia de los Muertos (Bay of the Dead) loomed large on the map and we wondered what this place might be like. The bay gets its name from an island – Isla de Muertos (Island of the Dead) a sacred burial ground for the indigenous people who once lived here. After breakfast we took off to the south over a pastoral landscape covered in patchy fog. Soon we could make out the dark figure of the bay and as we approached could see a maze of mangrove patches. We quickly decided to survey the islands around the mouth and run counterclockwise to cover all the features of the complex shoreline and out to the ocean. The tide was in and the chocolate water contrasted with the fresh green of the mangroves. As we came down to survey altitude, flock after flock of whimbrels and willets launched from edges, ricocheting back and forth along the tide guts. As we scrubbed the Island of the Dead, six Agami herons, one of the most ecologically mysterious herons of the New World, emerged from the western edge. The bay was teaming with water birds. In less than 30 minutes we had finished the survey and escaped the Bay of the Dead to continue the flight west along the Pacific toward Costa Rica.

This was the sixth day of aerial surveys designed to assess the abundance and distribution of waterbirds along the entire Pacific Coast of Panama (1,000+ kilometers). Bart Paxton and I, along with our pilot Carlos Dias, began the survey as close to the Panama-Columbia border as was allowed and worked west to Costa Rica. Along the way, we saw tapirs swimming in the ocean off the coast. We saw spectacular primary forests lining the lava shorelines of the Darien. While in a remote section on the second day we were overtaken by a powerful line of thunderstorms. With nowhere to hide we were forced to fly into the storm and take whatever beating it had to offer. As we approached Chiman, we saw clusters of people fishing from dugouts around the river mouths. Later we would see crews on commercial fishing boats steaming to port around Panama City – the stark contrasts of a country in the throws of modernity.

The Pacific coast of Panama varies from rugged volcanic shorelines to open beaches to extensive mudflats lined with mangroves. Beyond the shoreline villages and splendor of the coastal landscape, what we saw along the coast was waterbirds – huge numbers of waterbirds. During the six-day survey we mapped and counted nearly 500,000 waterbirds including shorebirds, seabirds and herons. Species had affinities for different shoreline types leading to variation in distribution on a large scale.

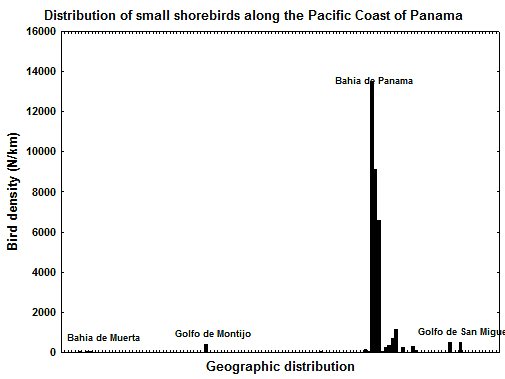

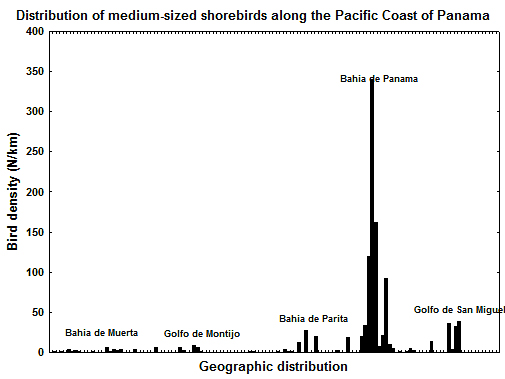

Shorebirds were the most abundant group of waterbirds, accounting for nearly 450,000 individuals divided among small shorebirds (390,000; dominated by western and semipalmated sandpipers), medium-sized shorebirds (13,000; dominated by black-bellied plover and short-billed dowitcher) and large shorebirds (41,000; dominated by willet and whimbrel). Small and medium-sized shorebirds were highly concentrated within the Bay of Panama where the density of small shorebird reached an incredible 14 birds per meter of shoreline. These birds favor extensive mudflats lined with mangroves.

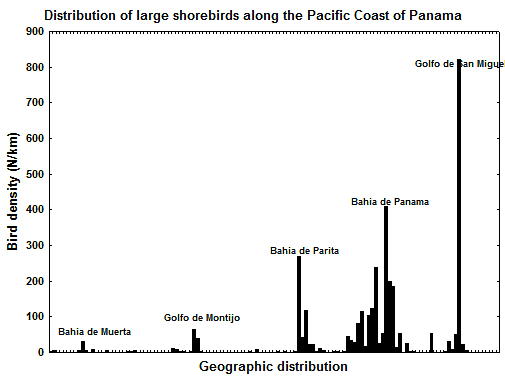

Large shorebirds included willets, whimbrels, black-necked stilts, marbled godwits and American Oystercatchers. Willets and whimbrel accounted for more than 90% of the group. Distribution of this group was comparable to small and medium shorebirds with the exception of very high numbers within the Gulfo de San Miguel. An exception to the mudflat-bay affinity was the American Oystercatcher. Large groups of oystercatchers were found on sandy shorelines around Punta Chame. Oystercatchers were also paired off and widely distributed on offshore islands.

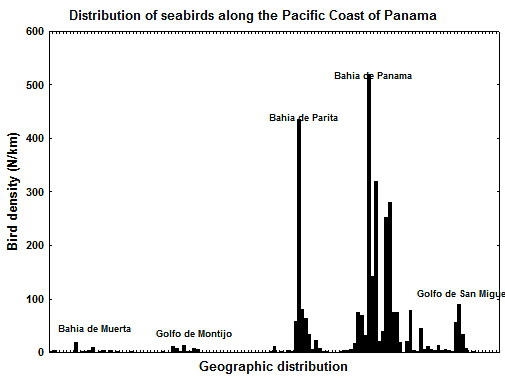

Like shorebirds, seabirds reached their highest densities within the large bays lined with mangroves. This group was dominated by neotropic cormorants and brown pelicans but also included good numbers of magnificent frigatebirds, laughing gulls and various tern species. Unlike the shorebirds that were associated with nearshore mudflats, seabirds were typically found foraging within nearshore waters or roosting within trees along the shoreline.

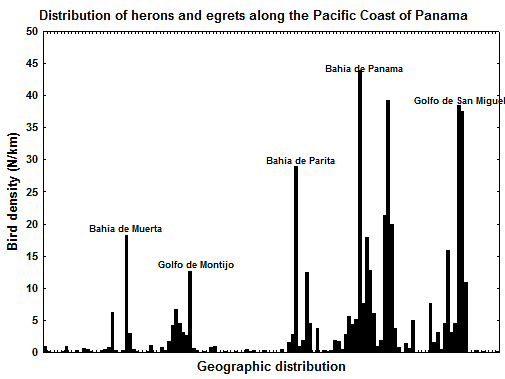

Herons and egrets were also associated with mangrove-lined bays but were more evenly distributed among the various bays available. Compared to the other waterbird groups, herons and egrets were also more associated with nontidal wetlands inland of the shoreline such that counts likely represent large underestimates. The Pacific coast of Panama is of high conservation value for many waterbird species, particularly during the boreal winter and migratory periods. Of particular importance are the large bays that are lined with mangrove forests and support wide mudflats. These bays represent globally significant areas with high energy availability. Conservation should focus on protection of mangroves that appear to support the broader food chain and limitations on upland deforestation that results in high erosion and silting of coastal bays.