60 years of bald eagle nesting data for the James River

Rogue states and the future of shorebird populations

July 13, 2021

Flying into the “Bay of the Dead”

October 1, 2021By: Bryan Watts

7/8/2021

On 17 January 1962, Harold Peters and Robert Bain took off from Byrd Field to survey for eagle nests along the James River. On 17 April 2021, Bryan Watts and Captain Fuzzzo Shermer took off from Williamsburg-Jamestown Airport to complete the eagle productivity survey along the James River. These two flights represent the bookends for 60 years of annual population and productivity surveys for bald eagles along the lower James River. The results of these surveys, including hundreds of flights and tens of thousands of nest checks, are archived at CCB. Collectively, the carefully collected records document events within a story of recovery for a population during a consequential time.

It is hard to imagine the anticipation and electricity that Peters felt as they launched from the runway. They were pioneers on a new adventure. The 1962 flight was at the dawn of aerial surveys for wildlife and the eagle population was reeling from exposure to agricultural chemicals. Armed with a regional map and a handful of nest locations that had been compiled mostly by Fred Scott and Charlie Steirly from ground surveys, they would visit these locations and survey broadly for unknown nests. They checked 21 nest structures, including 8 that were previously unknown. Sixteen of these nests were occupied by eagles or showed evidence of recent maintenance. They recorded 14 eagles during the flight, including 1 juvenile.

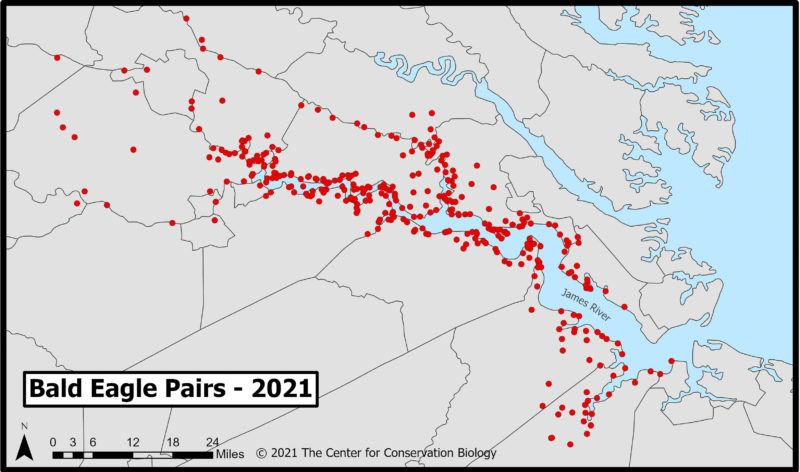

The situation was different for Watts and Shermer. Armed with a detailed GIS map with more than 400 coded nests and experience with every creek and forest patch from decades of flying the river, they would check 301 nests for productivity on this day alone. They would remain vigilant all day long to avoid the scores of eagles that now occupy the airspace along the river. They would experience a population that had been completely remade during the 60-year period.

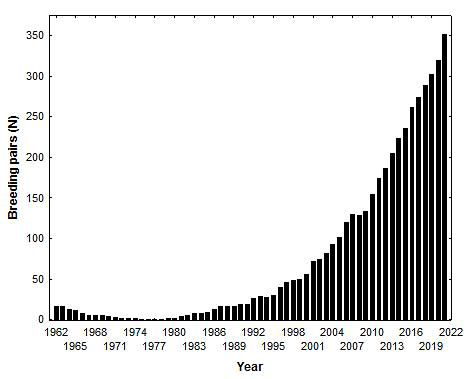

The survey of the James began on the tail end of a population crash but continued through a dramatic recovery and concluded during a period when the population is struggling to find its limits. In the spring of 1963, Charlie Hacker picked up an adult female from under a nest on Jamestown Island that was experiencing convulsions and would later die of DDT toxicity. The event was symbolic of the next 15 years. Over an 11-year period during the 1960s and 1970s, the population produced only three young. The population then bottomed out with no known nesting pairs on the river from 1974 through 1978. Following this low period, there was a glimmer of hope during a flight on 19 January 1979, when Mitchell Byrd located an active nest on Upper Chippokes Creek that would later produce two young. The population reached 18 pairs by 1990, 57 pairs by 2000 and 352 pairs during the 2021 survey.

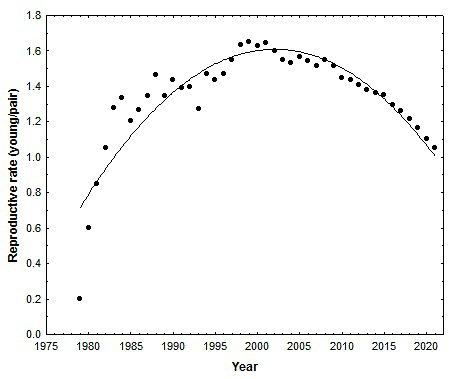

More interesting than the population growth is the change in reproductive rates documented over the 60-year period. During the early 1960s, young production was about 25% of that needed for population maintenance. Emerging from the DDT era, productivity rose through the 1980s and 1990s, reaching a boom time during the late 1990s and early 2000s when pairs were producing twice the number of young required for maintenance. This excess production would rapidly saturate available space and then create a negative feedback as floaters began to challenge territory holders for breeding space. Frequent challenges have forced males to guard broods rather than hunt to provide food, a shift that has increased the number of nest failures and reduced brood sizes. In just 20 years the success rate (producing at least 1 chick) has declined from more than 80% down to 61% and 1-chick broods have replaced 2-chick broods as the most common brood size. Once representing 10-15% of all broods, 3-chick broods accounted for only 4% of broods in 2021. Overall reproductive rates are now falling toward maintenance levels and should eventually ease the territory wars currently raging within the population.

Although several papers have been produced by CCB on various aspects of the eagle population within the Chesapeake Bay, several new aspects of eagle ecology and behavior need to be released from the 60-year dataset. This work will begin in earnest during the fall of 2021.