NEW PAPER: Whimbrel populations differ in trans-Atlantic pathways and cyclone encounters

Coming Home – To the Marshes

June 23, 2021

Regulating Bunker – with osprey

July 13, 2021By: Bryan Watts

7/1/2021

For centuries bird people sat along the shoreline during the fall and watched as birds left the coast, flying directly out to the ocean’s horizon and wondered why they were flying into the abyss. As we learned more about the winter ranges of species, we began to entertain the idea that birds were following trans-Atlantic pathways between breeding and winter grounds and began to ask questions about which species could physically make these crossings from various jumping-off points. As we learned more about the formation and distribution of tropical storms, we began to ask how birds “out-to-sea” were able to cross hurricane alley during the peak of storm activity. Many mysteries about trans-Atlantic crossings persist to the present day. However, over the past two decades the development of ever smaller tracking devices has opened the door to addressing many questions that were unreachable just one generation ago.

During the spring of 2008, CCB and partners began to deploy small satellite transmitters on the two populations (Hudson Bay and Mackenzie Delta) of whimbrel that use the Western Atlantic Flyway. It has taken over a decade to compile enough trans-Atlantic crossings to begin to address several long-held questions about migration over the sea. Findings related to population-specific pathways, frequency of storm encounters and response to encounters are the focus of a recent paper published in Nature – Scientific Reports.

Read paper: Whimbrel populations differ in trans-Atlantic pathways and cyclone encounters

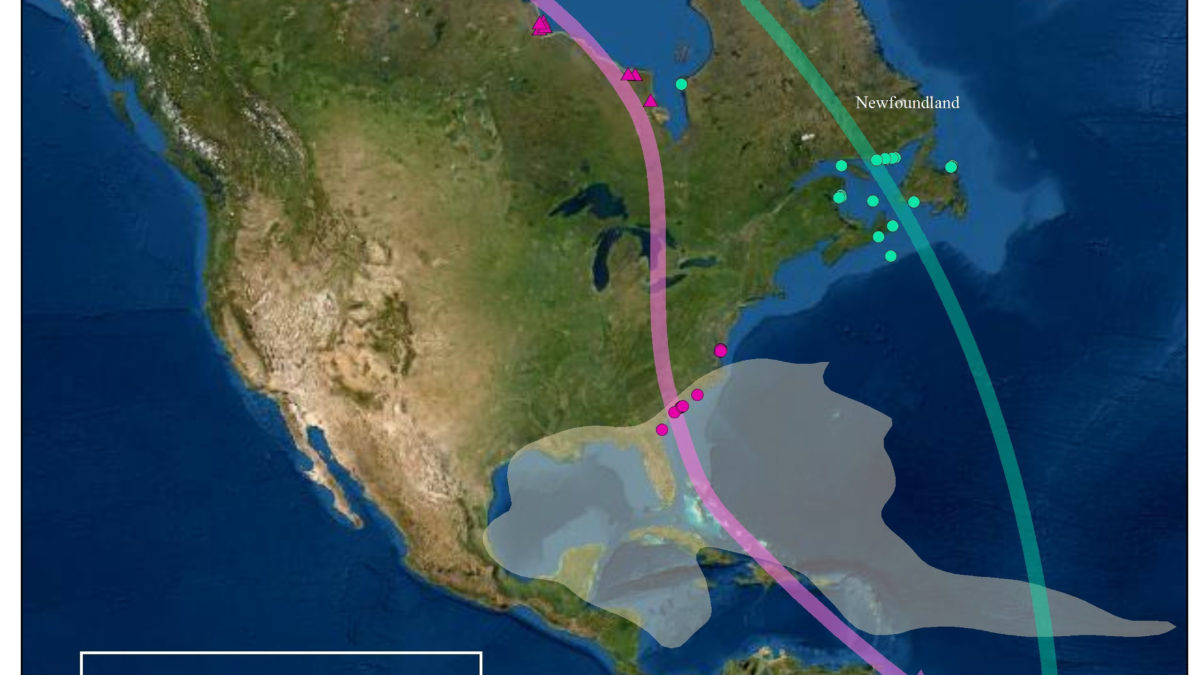

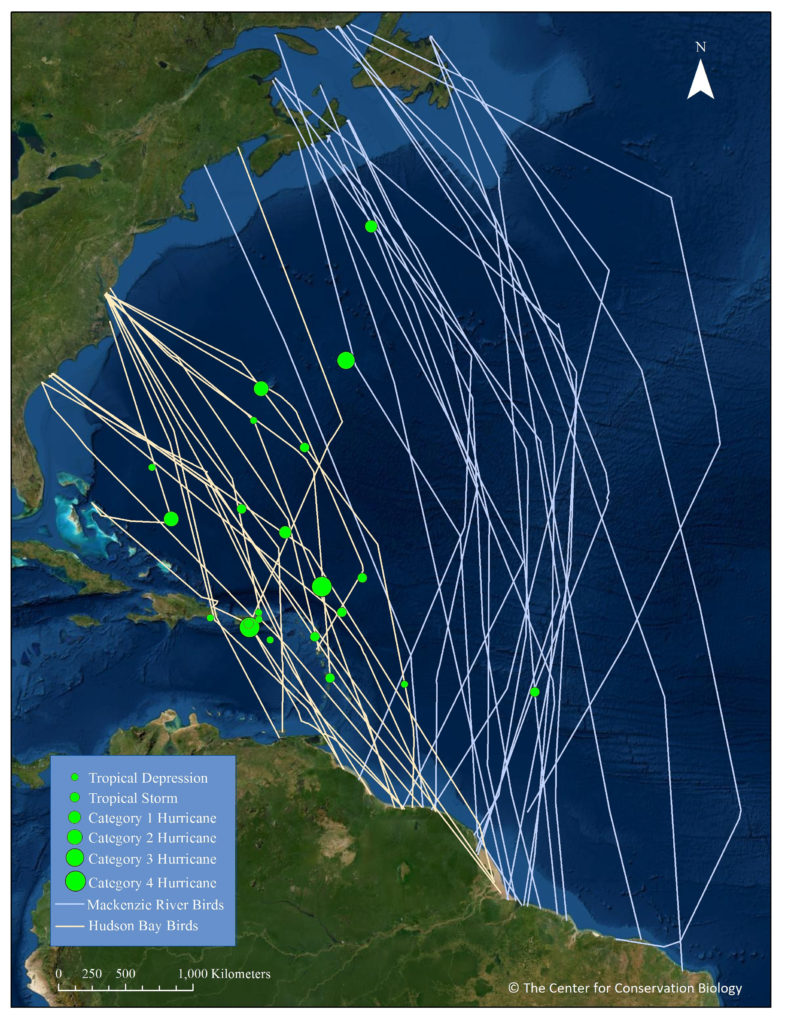

Although the two whimbrel populations winter together along the northern coast of South America, they take dramatically different pathways to reach winter grounds. Mackenzie Delta whimbrels stage in and depart from Atlantic Canada, flying nonstop far out to sea for an average of 6.1 days along a route that is 5,400 kilometers long. Hudson Bay whimbrels stage in and depart from the south Atlantic Coast and fly directly across the Caribbean Basin for an average of 4.5 days along a route that is 3,600 kilometers long. These distinct pathways come with different downstream consequences.

The two pathways differ in their exposure to Hurricane Alley such that the populations have different storm encounter rates. Mackenzie Delta birds fly around the region of greatest storm activity and remain over cooler waters where storm formation is uncommon. Only 3 of 26 crossings encountered storms. Hudson Bay birds, however, fly directly through the region of highest storm activity and 13 of 21 crossings encountered storms. Due to their routes, birds from the two populations also encountered storms of different strength, with Hudson Bay birds crossing through the area where storms have developed into monsters. Half of the Hudson Bay birds that encountered storms were grounded on Caribbean islands. Grounding increased the trans-Atlantic passage time from 4.5 days to more than 30 days, increasing the birds’ exposure to additional storms, hunting and predators. Three birds were lost while grounded, including two that were shot by hunters and one that was taken by a predator.

The two whimbrel populations have developed two strategies to cross the Atlantic that appear to work. Mackenzie Delta birds follow a longer route that requires a much longer sustained flight but avoids most storms. Hudson Bay birds follow a shorter route through the most dangerous part of Hurricane Alley. Birds that do not encounter a storm have a relatively short passage to the winter grounds. Those that encounter storms use Caribbean Islands as a safety net. However, stopping over on the islands is not entirely safe. Hurricane-aided hunting, additional storms and predators offer hazards during stopovers. Even so, given the frequency of storm encounters, it is unlikely that this route would be viable without the safety net of the islands.

Hundreds of millions of birds including scores of species make trans-Atlantic crossings each fall. Are the pathways used by whimbrels superhighways used by many of these species or are there other sustainable pathways used by other groups of species – pathways that come with their own set of unique tradeoffs? The analysis of whimbrel tracks is breaking new ground in our efforts to understand the constraints migrants face when crossing one of the most daunting barriers on the planet. This journey of discovery is just beginning. There is little doubt that as tracking technology advances and as we stand up new tracking projects involving more species that we will be able to see a broader range of strategies used by birds to cross the Atlantic.